Archaeologists Were Surprised to Find the Mummy of an Egyptian Priestess in This 'Empty' Coffin

An ancient Egyptian coffin, previously thought to be empty, holds the mummified remains of an Egyptian priestess who lived 2,500 years ago.

The University of Sydney in Australia acquired the sarcophagus more than 150 years ago, but it sat untouched in the university's Nicholson Museum until late 2017, when researchers removed the coffin's lid.

As soon as they looked inside, they were taken aback by the ragged remains of a mummy. [In Photos: Oldest Images of a Pharaoh]

"The records previously said the coffin was empty or [filled] with debris," Jamie Fraser, the lead investigator and senior curator at the museum, told Deutsche Welle (DW), a German news outlet. "There is a lot more to it than previously thought."

An analysis of the newfound mummy reveals that it is the remains of a person who died at about about 30 years of age, the researchers said. According to hieroglyphs on the coffin's side, the person was a priestess named Mer-Neith-it-es who lived in about 600 B.C.

"We know from the hieroglyphs that Mer-Neith-it-es worked in the Temple of Sekhmet, the lion-headed goddess," Fraser told DW. However, the ancient Egyptians sometimes reused coffins, so it's possible that the mummy isn't that of the priestess but rather an interloper, the researchers said.

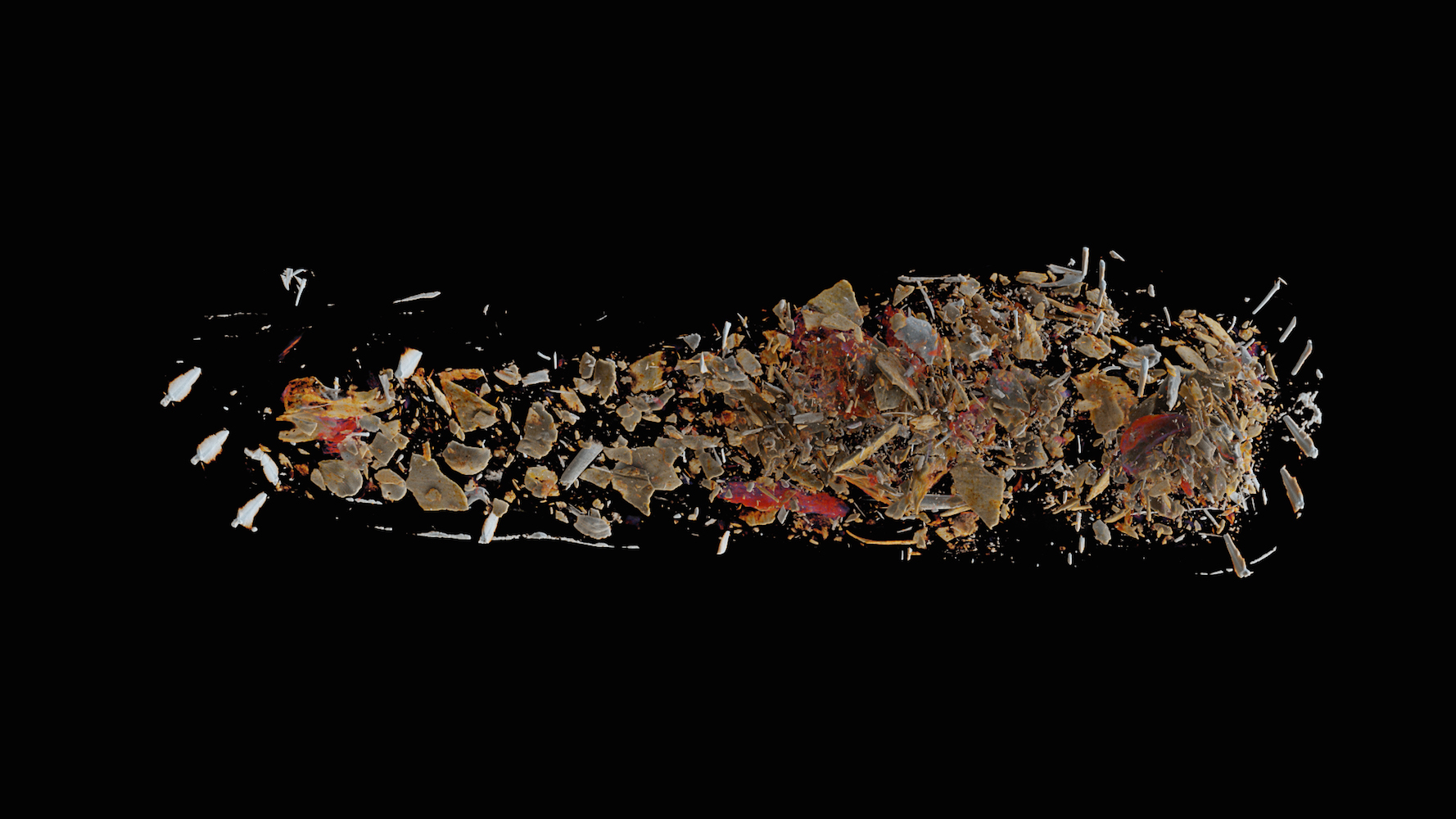

To learn more about the mummy, the researchers scanned the remains with a computed tomography machine, which takes thousands of X-rays that can then be pieced together into a digital 3D image. These scans showed that the mummy contains several bones, bandages, resin fragments and upward of 7,000 glass beads that were sewn onto a funeral shawl, DW reported.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In particular, the researchers noticed that resin had been poured into the mummy's skull after the brain was removed, Egyptologist Connie Lord told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC).

However, grave robbers apparently reached Mer-Neith-it-es before the Australian researchers did, as her body was heavily disturbed. Even so, a study of her remains can inform scientists about the diet and diseases that affected ancient Egyptians, Fraser said.

Charles Nicholson, the university's former chancellor, acquired the Egyptian coffin — as well as three others that contained ancient mummies — in 1860. All four coffins will be put on display at the Nicholson Museum next to a display about research on the newly uncovered mummy, according to the ABC.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.