Does It Fart? 10 Fascinating Facts About Animal Toots

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Animal Gas

Cows do it. Koalas do it. But birds don’t. Fart, that is.

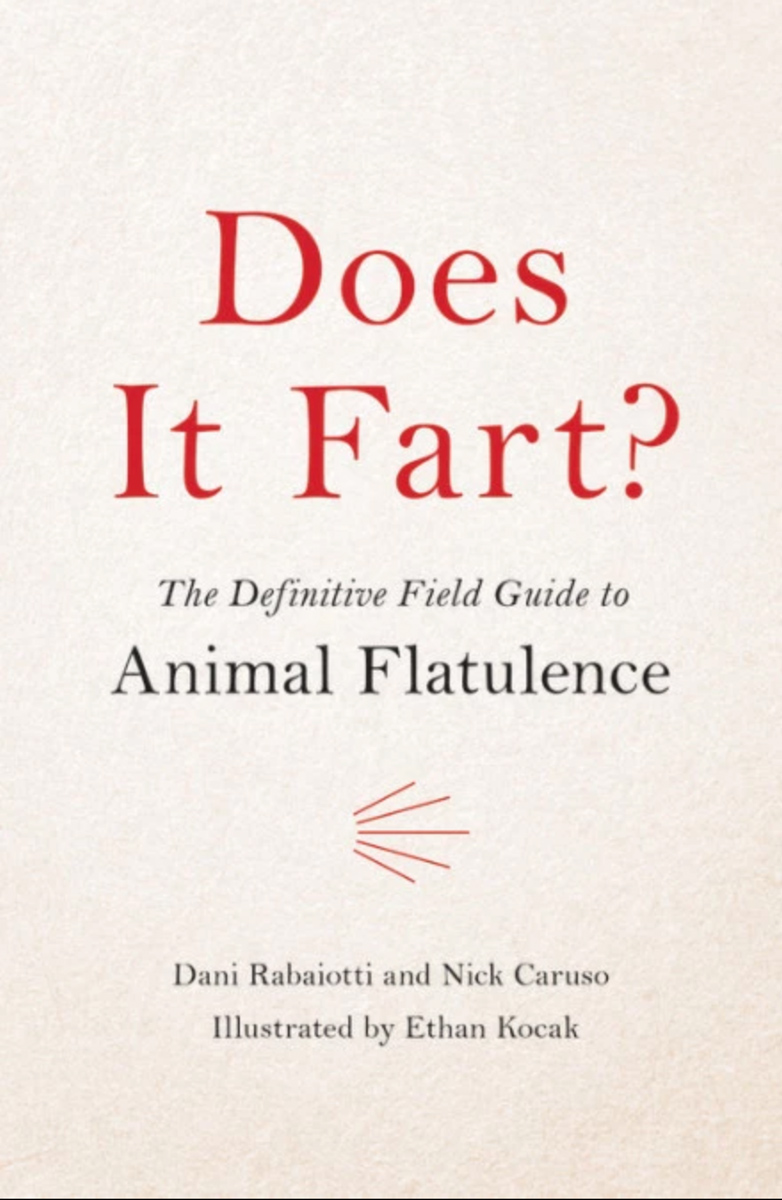

In a new book aptly titled "Does It Fart?", zoologist Dani Rabaiotti and ecologist Nick Caruso catalogue the farting habits of animals across the web of life, with plenty of facts that elicit laughs and gagging. Here are a few of Live Science’s favorite farting facts from the book (to be released in the U.S. on April 3, 2018).

Sonoran Coral Snake

Like all snakes, the Sonoran coral snake farts. It actually uses its farts as a first line of defense against predators. When threatened, the snake raises its tail and pulls air into its cloaca (basically its butt) and then emits it again as a loud pop.

Baboons

Since humans fart, it’s no surprise that their primate cousins do as well. When female baboons are ready to mate, their sexual organs and bottom swell, which reportedly makes any gas they pass particularly fragrant.

Bats

Scientists don’t know for sure if bats fart. They have the right bacteria in their digestive system to be able to produce the gas that leads to farts, but their digestion is fairly rapid, so there may not be enough time for farts to build up.

Millipede

The digestive system of millipedes may be relatively simple, but the resident methane-producing microbes that help them break down the leaves they munch mean they definitely fart. And the bigger the millipede, the more methane, so the bigger the farts. The Giant African millipede (pictured above) can reach 15 inches (38 centimeters) long.

Horses

Horses are frequent farters. They eat lots of hard-to-digest plant matter and so have lots of resident microbes to help break their food down, and create gas in the process. Their colons are also quite long — about 11.5 feet (3.5 meters) — meaning lots of time for that gas to build up.

Bolson Pupfish

This fish feeds off the algae that grows in the shallow pools in which it lives in northern Mexico. In the warm summer months, the algae produce gas that the fish also ingest. They can build up so much gas in their intestines that they start to float, which puts them at risk of becoming a bird’s dinner. To bury themselves back in the sand, where they prefer to hang out, they must fart out that gas.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dinosaurs

No one was around to hear — or smell — dinosaur farts. But one type of dinosaur, the sauropods, ate plenty of plants and may have had similar digestive systems, including methane-producing bacteria, to the large herbivores alive today. One study cited in the book estimates each dinosaur could have produced as much as 4 pounds (1.9 kg) of methane a day.

Whales

Whale farts, like the animals themselves, are epically large, though they’ve only been captured on camera a few times. But researchers who have been caught downwind of a tooting whale report it’s a rather smelly situation.

Frogs

Frogs are another species whose farting status is uncertain. For one thing, their sphincter muscles aren’t very strong, so any gas escaping their rear end may not cause enough vibration to be audible.

Sloth

Like the animal itself, the digestive system of a sloth is very slow, taking days to digest the leaves it eats. Their simple gut microbes mean they don’t produce flatulence; instead, the methane those microbes give off is absorbed into the bloodstream and simply breathed out.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus