Imaging Reveals Medieval Manuscript Hidden in Book Binding

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In the mid-16th century, a bookbinder picked up a piece of parchment — one that was already centuries old — and used it to bind a book of poetry. This parchment's text remained unreadable for nearly 500 years, but now, thanks to state-of-the-art imaging techniques, people can read its words once more, according to a new study.

An analysis of the sixth-century text revealed that it was part of the Roman law code. Whoever made the poetry book likely considered the text to be outdated, as at that point, society was using the church's code, rather than Roman laws, the researchers said.

The finding is a remarkable one, as it can likely be used to help decipher the text on other parchments used as bookbinding materials, the researchers said. [Voynich Manuscript: Images of the Unreadable Medieval Book]

Between the 15th and 18th centuries, bookbinders routinely recycled medieval parchments so they could use them as bindings for new, printed books. (A parchment is a thin and stiff piece of animal skin, usually from sheep or goats, that people wrote on.) Scholars have long known about this practice, but though they were interested in the text written on these old parchments, they were unable to read them.

"For generations, scholars have thought this information was inaccessible, so they thought, 'Why bother?'" the study's senior researcher, Marc Walton, a senior scientist at the Northwestern University-Art Institute of Chicago Center for Scientific Studies (NU-ACCESS), said in a statement. "But now computational imaging and signal processing advances open up a whole new way to read these texts."

Poetry book

The book itself is a 1537 copy of "Works and Days" by the Greek poet Hesiod, a writer who likely lived during the same period as Homer. Northwestern purchased the book in 1870, and the copy is now the only imprint with its original slotted parchment binding.

At first, only the binding caught the researchers' eyes. Then, they began wondering about the text written on the parchment in the binding. But a closer inspection showed that the bookbinder had attempted to remove the text, likely through washing or scraping the parchment, the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Luckily, two ghostly columns of writing remained, as well as comments in the margins.

"The ink beneath degraded the parchment, so you could start to see the writing," the study's lead researcher Emeline Pouyet, a postdoctoral fellow in NU-ACCESS, said in the statement. "That is where the analytical study began."

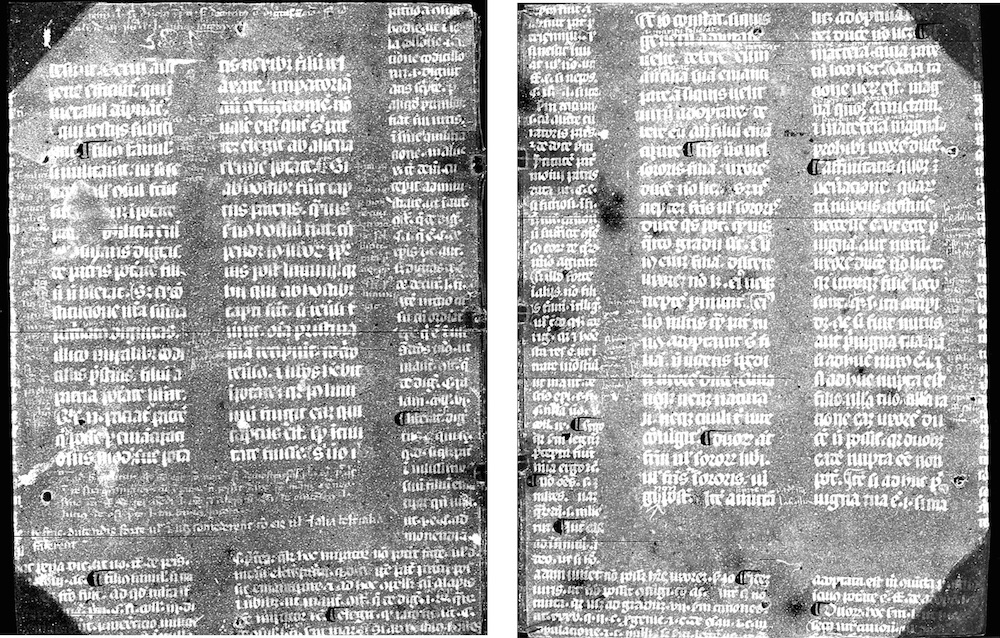

Walton and Pouyet tried a visible-light hyperspectral imaging technique — a method that identifies the spectral range for every pixel in an image — to highlight the words, but this only made the text slightly clearer, because the parchment had degraded irregularly. Then, they tried X-ray fluorescence imaging, a technique that gave data on the ink composition, but didn't make the text any more readable, they said.

Finally, the researchers hit gold: The team sent the book to the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) in Ithaca, New York, where powerful X-rays fully imaged the text and its marginal comments. When the researchers sent the results to study co-researcher Richard Kieckhefer, a professor of religion and history at Northwestern, he announced that it was a sixth-century Roman law code with notes referencing the church's canon law. [Image Gallery: Medieval Art Tells a Tale]

It's possible that this parchment was originally used in a university setting where students studied Roman law as a basis for understanding canon law — a common practice during the Middle Ages, the researchers said.

Future steps

Not all rare books, however, can be sent off-site for CHESS analysis. So, using a machine-learning algorithm, the researchers, along with Northwestern electrical engineering and computer science professors Aggelos Katsaggelos and Oliver Cossairt, found another, better way to image parchments such as this one.

Rather than use just one technique, a combination of two — visible hyperspectral imaging and X-ray fluorescence — provided the best results, they found.

"By combining the two modalities, we had the advantages of each," Katsaggelos said in the statement. "We were able to read successfully what was inside the cover of the book."

The team is now looking for other parchments to decipher.

"We've developed the techniques," Walton said. "[Now], we can go into a museum collection and look at many more of these recycled manuscripts and reveal the writing hidden inside of them."

The study was published online in the August issue of the journal Analytica Chimica Acta.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus