This Terrifying, Toothy 'Monster' Is the World's Deepest Living Predator

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

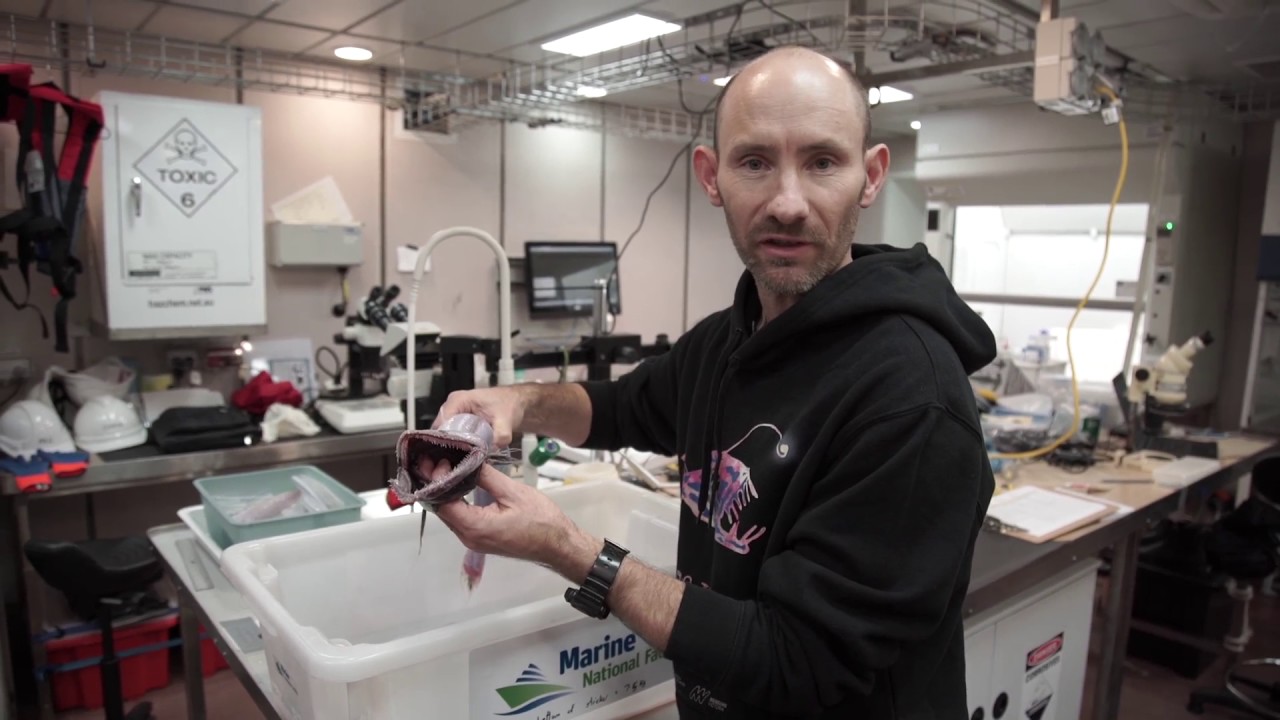

In the inky darkness of the ocean's abyss swims the world's deepest living superpredator: a fish with a long, eel-like body; the face of a lizard; and a mouth full of sharp teeth.

Scientists aboard a research vessel unexpectedly found the so-called lizard fish while trawling (dragging a net underwater) off the coast of eastern Australia on June 4, according to a blog post on the Australian Marine Biodiversity Hub.

"This terrifying terror of the deep is largely made up of a mouth and hinged teeth, so once it has you in its jaws, there is no escape: The more you struggle, the farther into its mouth you go," Asher Flatt, the vessel's onboard communicator, wrote in the blog post. [Photos: The Freakiest-Looking Fish]

This terrifying creature's scientific name is Bathysaurus ferox, which means "fierce deep-sea lizard," and its common name comes from its lizard-like face. It lives 3,280 feet to 8,200 feet (1,000 to 2,500 meters) under the water's surface. Like other lizard fish, B. ferox is benthic, meaning it lives along the ocean floor, where it often buries itself in sediment, hiding until it can ambush prey.

"I would describe them as lie-and-wait predators," said John Sparks, a curator of ichthyology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City who was not involved in the recent expedition. "They bury themselves in the sand or mud, lie still and if something swims by, they dart out and eat it."

Aquariums have tried putting shallow-water lizard fish — a sister group of the deep-water lizard fish — in viewing tanks with other fish, but "they eat everything in there," Sparks said. "They don't make good aquarium pets."

They're not very appetizing, either, because the meat is "mushy," Sparks said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Most lizard fish gobble up other fish and squid, but they eat "anything they can get their mouth around," Sparks said.

He added that the lizard fish is a hermaphrodite, so it has both ovarian and testicular tissues in its reproductive organs. This means that any B. ferox can shack up with any other B. ferox it swims across, giving it a mating advantage in the sparsely populated deep ocean.

The roughly 20-inch-long (50 centimeters) B. ferox also has an unusually large liver that accounts for 20 percent of its body weight, according to a 1985 study published in the Canadian Journal of Zoology. Other lizard fish have smaller livers that amount to just 5 percent of their body weight, the study's researchers found.

It's unclear why B. ferox's liver is so large, but the fish might use it to store energy, the study's researchers said.

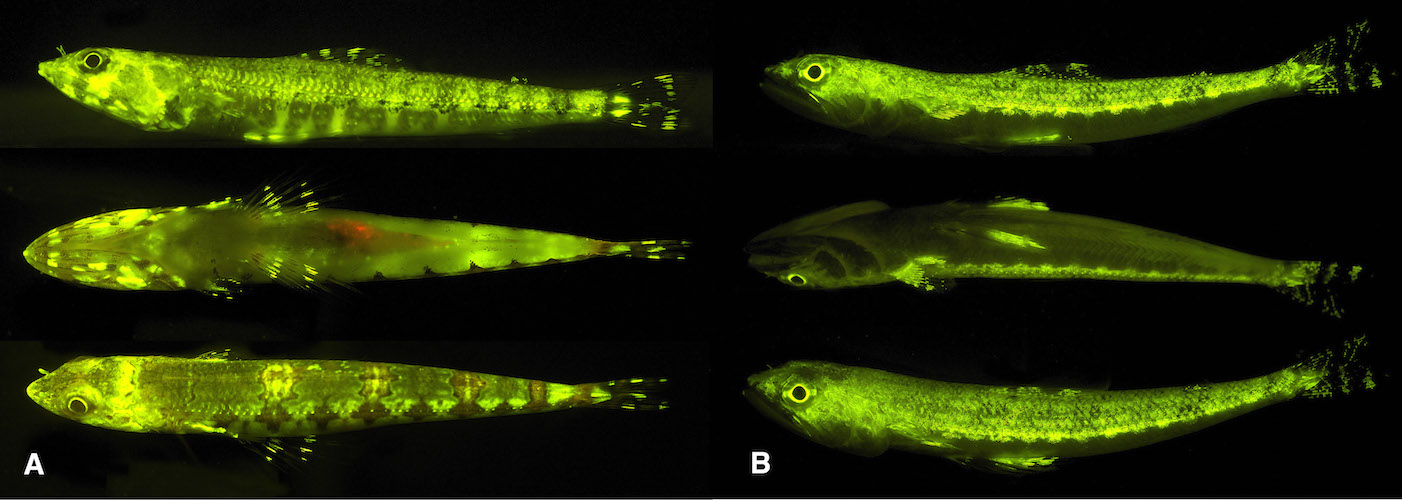

The fish may have another quirky feature: Other deep- and shallow-water lizard fish are fluorescent, but it's not yet clear whether B. ferox is, too, Sparks said. If it were, it would likely get enough ambient light to glow, even at 8,200 feet underwater, he noted.

"You don't need that many photons to energize it," Sparks said.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus