Should a 'Resurrected' Dodo or Mammoth Get a New Name?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

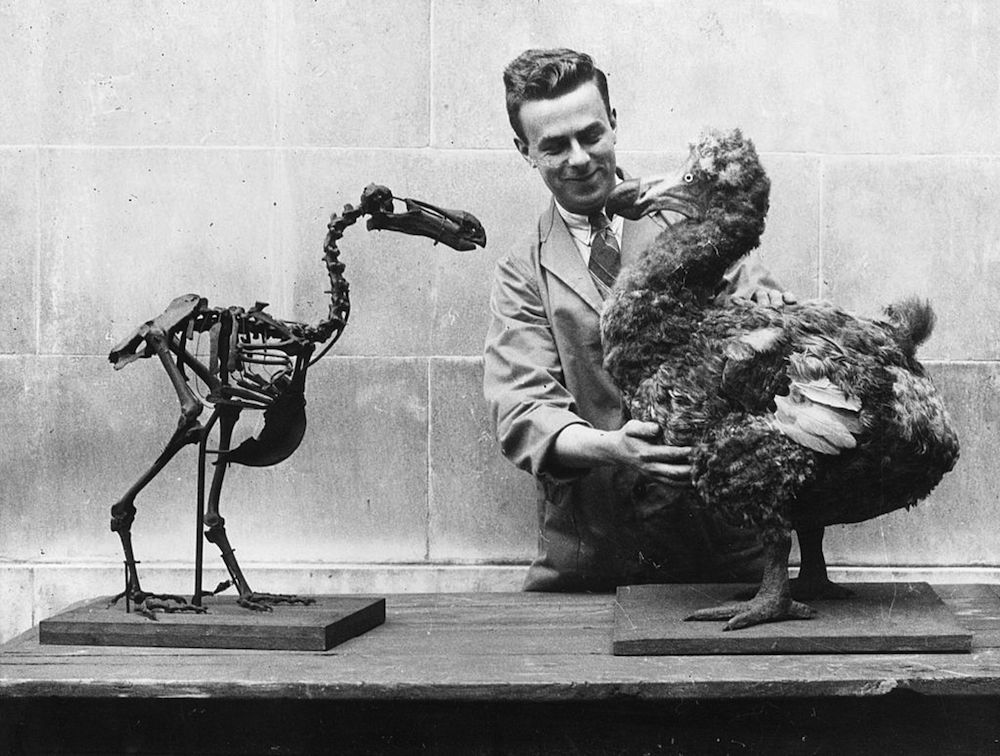

If scientists could resurrect extinct animals — such as the dodo, Columbian mammoth or Tasmanian tiger — should these animals have different names that distinguish them from the original species?

In a new opinion paper, a group of scientists said yes, arguing that a modified name would give de-extinct animals an appropriate distinction from the natural species, as well as a conservation status that could help protect them legally.

In practice, researchers could take the original scientific name, but add "recr," an abbreviation of "recrearis," the Latin word for "revived." This addition, for instance, would change the Columbian mammoth's scientific name from Mammuthus columbi to Mammuthus recr. columbi, said the paper's lead author, Axel Hochkirch, lab manager in the Department of Biogeography at the University of Trier in Germany. [10 Extinct Giants That Once Roamed North America]

"If the DNA amount of [a resurrected] Mammuthus columbi is not high enough [compared with the original mammoth], one could even create a new species name, [such as] Mammuthus recr. americanus," Hochkirch told Live Science in an email. "If each resurrected species is marked with "recr.," it is very clear to all that we speak about something artificial, something that differs from the real mammoth."

De-extinction techniques

There are many hurdles to bringing back an extinct species. The first animal brought back from extinction — a wild goat called a bucardo, also known as a Pyrenean ibex (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica) — died a few minutes after its birth because of a lung defect, according to a 2009 study published in the journal Theriogenology. Likewise, efforts to bring back the extinct Australian gastric-brooding frog (Rheobatrachus silus) "were not viable," the researchers wrote in the new opinion paper.

In essence, researchers need a full copy of an extinct animal's DNA to revive that species, a difficult thing to obtain, because DNA begins to degrade the instant an animal dies. This occurs largely from exposure to bacteria, oxygen, water, ultraviolet light, and enzymes from both the animal itself and the environment, Live Science reported previously.

But de-extinction techniques are constantly improving. These methods include back breeding (breeding an existing animal to have traits of a closely related, extinct species), cloning (putting reproductive material of an extinct species into the womb of a closely related, living species) and genomic engineering (filling in missing DNA information from an extinct species with the DNA of a closely related animal).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Because of these advances, the Species Survival Commission of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) published de-extinction guidelines in 2014. While the guidelines highlight the uncertainties in classifying de-extinct animal species, the new opinion piece goes a step further, Hochkirch said.

For starters, any animal that's resurrected will likely be a hybrid of the original animal and another species, or a "proxy," for the original, he said. These differences will partly be genetic and partly due to other factors: the animal's epigenetics (environmental forces that can change gene expression), microbiome (the bacteria in the body) and learned behavior, he said.

A modified name would remind people that the resurrected animal isn't an exact copy of the original, Hochkirch said. Moreover, a revised name would remind government officials that the revived species would need extra protections, which may be different than protections that were provided to the original species, Hochkirch said. [6 Extinct Animals That Could Be Brought Back to Life]

No to "recr."

However, the new naming proposal appears to simplify how evolution works and raises questions about how the system would be implemented, said Beth Shapiro, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who was not involved with the editorial.

"How much of the genome has to be modified in order to earn the [recr] 'tag'?" Shapiro asked. "Would an elephant with two mammoth genes be considered sufficiently de-extinct? Who gets to decide?"

In an email to Live Science, Shapiro wrote, "I think 'recr' is probably inappropriate, as they are not revived copies of something, but instead hybrids. Adding this to their name will foster more misunderstanding and mistrust of the true intentions of this work, which is to facilitate the survival of species that are under threat of extinction."

The opinion piece will be published online Friday (June 9) in the journal Science.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus