Editor's Note: This article was updated at 1:30 p.m. E.T.

A hormone that scientists have known about for decades may be able to put women's eggs into hibernation, which could protect the eggs from damage during chemotherapy, new research suggests.

The egg-hibernation technique, which has so far been tested only in mice, could also be used as a general contraceptive, or to lengthen a woman's fertile years and delay the onset of menopause, said study co-author David Pepin, a reproductive biologist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

"It's a completely different mechanism of contraception that opens up a lot of applications, including this one, which is to protect the ovary from chemotherapy," Pepin said. [The Future of Fertility Treatments: 7 Ways Baby-Making Could Change]

Ovarian reserve

Fertility clinics have long used the anti-Müllerian hormone, or AMH, as a rough measure of a woman's ovarian reserve, or how many eggs she has left. A woman is born with more than a million immature eggs, which either develop into mature eggs each month or are destroyed as she ages. At menopause, a woman has fewer than 1,000 eggs left, according to research published in 2004 in the journal Human Reproduction.

Scientists also know that early in embryonic development, the hormone plays a role in determining whether primitive reproductive structures develop into female organs. For instance, in male embryos, the fetal testes produce a surge of both testosterone and AMH in the early stages of gestation, which inhibits the formation of the fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix and vagina, Pepin said.

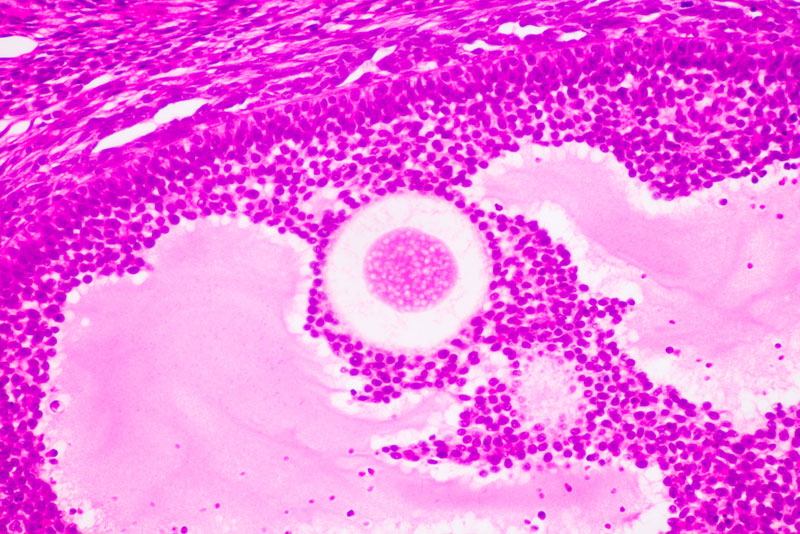

Pepin and his colleagues stumbled upon the new findings by accident, the researchers said. Study co-author Dr. Patricia Donahoe, a researcher at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, and Pepin had been studying the potential of AMH to prevent ovarian cancer in mice. When Pepin looked at the ovaries of mice treated with AMH, he found that they had shrunk to a size typically found in a newborn mouse, and the ovarian follicles (structures inside the ovary that contain the immature eggs) were basically undeveloped.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The ovaries "were basically in hibernation," Pepin told Live Science.

AMH is normally secreted by a type of cell called granulosas, which surround an immature egg. Pepin's team found that the release of AMH from the granulosa cells prevented eggs from maturing.

Hit the pause button

Because of the AMH's unique mechanism of action — it prevents eggs from maturing — Pepin and his colleagues wondered whether the hormone could help prevent damage to a woman's eggs when she undergoes chemotherapy, Pepin said.

"Chemotherapy is very damaging to dividing cells," Pepin told Live Science. For instance, hair follicles split in two very rapidly, which is why many people lose all their hair during chemotherapy. Similarly, "the ovarian follicles are constantly growing, so they get really heavily damaged by chemotherapy," Pepin said.

In some women, chemotherapy not only damages the eggs, but may also hasten the onset of early menopause. This is linked to cognitive declines, osteoporosis, heart disease and other health risks.

So the team wanted to see whether the method worked to prevent conception and protect the ovaries during chemotherapy, Pepin said. The method did work in mice, the researchers found. However, the mice needed daily injections of the hormone, and it's still not known whether the treatment would have side effects in humans, Pepin added. (Current contraceptives can't offset this damage, because they work only after an egg has matured — to prevent ovulation, which is the release of an egg from the ovary, Pepin said.)

Over the long term, the team hopes to study the hormone's potential to preserve fertility in younger breast cancer patients, the researchers said. The idea is that shots delivered through a course of chemotherapy could keep oocytes (immature egg cells) dormant, thereby shielding them from damage, Pepin said.

Another long-term possibility is that women could one day hit the pause button on their fertility, he said. The hormone could act as a contraceptive that not only prevents pregnancy, but also prevents eggs from being depleted, Pepin said. That, in turn, could allow women to have babies later in life and delay or even prevent menopause.

However, it's still not clear whether AMH is the key player in the aging of a woman's eggs, Pepin said.

"Maybe you maintain the egg numbers," Pepin said. "You have an ovary that looks young, but the quality of eggs may not be as good."

The findings were published on Monday (Jan. 30) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Editor's Note: This article was edited to correct the spelling of AMH in one instance and to clarify that AMH prevents eggs from being depleted, not necessarily from aging.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.