Were Egyptian 'Pot Burials' a Symbol of Rebirth?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

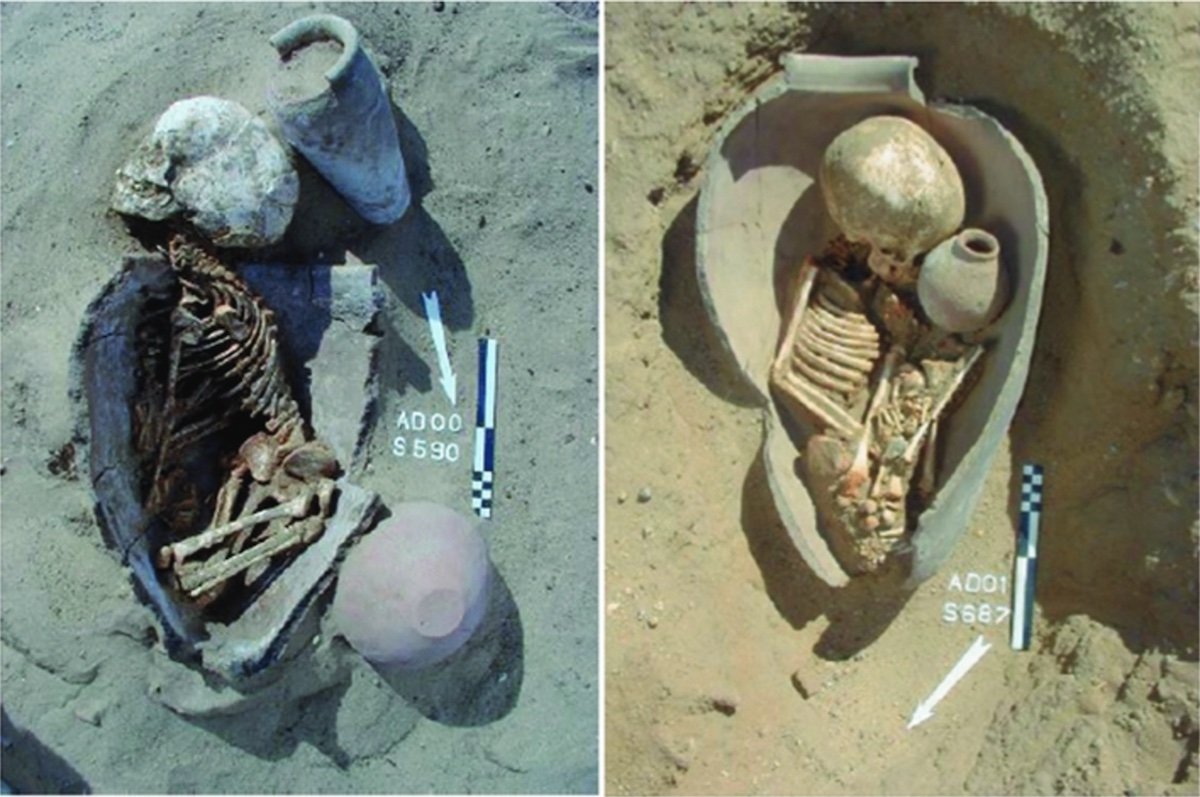

Ancient Egyptians who buried their deceased kin in pots may have chosen the burial vessels as symbols of the womb and rebirth, scientists argue in a new paper.

Pot burials in ancient Egypt have long been considered the domain of the very poor. In a paper published in the journal Antiquity, however, archaeologists Ronika Power of the University of Cambridge and Yann Tristant of Macquarie University in Australia assert that pots weren't just a last-ditch choice for the desperate. Instead, they wrote, pots may have symbolized eggs or the womb, and their use may have indicated beliefs that the dead would be reborn in the afterlife.

"[I]t is hard to dismiss the visual similarities between pots laden with human bodies with limbs contracted into the so-called 'foetal' or 'sleeping' position and gravid uteri or eggs," the researchers wrote. "It is clear that further study is required to untangle the symbolic meaning of this particular mode of burial, which has clear associations with gestation and (re)birth." [25 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

High-status dead?

Children, infants and fetuses in ancient Egypt are often found buried in pots, and for that reason, researchers have downplayed the importance of this ritual as mere rubbish disposal, according to the study researchers. But being buried in a recycled household pot doesn't necessarily indicate that the babies and children interred in this way were considered nothing more than garbage, Power and Tristant wrote. Ancient cultures recycled everything, they said, and even high-status people were sometimes buried in reused tombs or sarcophagi.

"[If] an object was no longer viable for its initial function, it was not immediately disposed of, but rather repaired, functionally or symbolically transformed, stored for future reuse, or broken down to be integrated into another object," Power and Tristant wrote.

What's more, the researchers wrote, many adults were buried in pots, too. Pot burial sites are found up and down the Nile River. At least four sites featured adult pot burials throughout the Greco-Roman period of Egyptian history (332 B.C. to A.D. 395), Power and Tristant wrote. At five sites, including the quarry town of Gebel el-Silsilaon the banks of the Nile, only pot burials of adults — none of children — have been reported, they added.

Nor is it clear that families who chose pot burials were universally poor, the researchers wrote. In one case, they said, an infant buried around the end of the Old Kingdom period and the beginning of the First Intermediate period (approximately 2181 B.C.) was found in a pot along with many expensive beads, including seven covered with gold foil.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Born again?

If pots weren't just something used by the poor because they had nothing else, they may have had symbolic value in their own right, Power and Tristant said. There are a few references to the womb as a pot or vessel in ancient Egyptian scrolls and wall carvings, they wrote, including a wall carving in a chapel in the Saqqara necropolis that shows dancers chanting, "See the pot, remove what is in it!" in reference to birth.

Pots may have also reminded ancient Egyptians of eggs, which were sometimes associated with the inner coffin of a burial, Power and Tristant wrote.

"As the symbols of life par excellence, it is hard to recommend a more fitting means to facilitate the transition into the afterlife," they wrote.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus