Man Dies of Flesh-Eating Bacteria from Ocean: What Is Vibrio Vulnificus?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

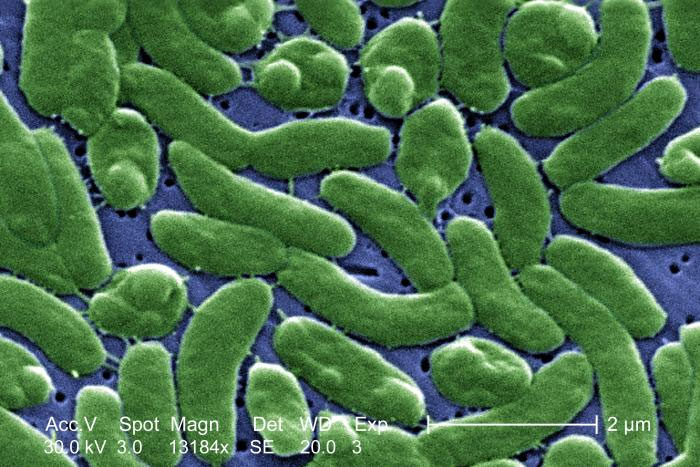

A man in Maryland died just days after he developed a rare infection from a type of flesh-eating bacteria that live in ocean water.

The man, Michael Funk, 67, had a cut on his leg that came into contact with the salty water in a bay near his home in Ocean City, according to Nature World News. The cut allowed a type of bacteria called Vibrio vulnificus to enter his bloodstream. Soon, Funk began to experience intense pain in his leg and was taken to the hospital, where doctors removed infected skin, and later, amputated his leg. But within four days, the fast-moving infection had taken his life.

Vibrio vulnificus is found in warm coastal waters, and is present at higher levels between May and October, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

People can become infected with the bacteria in two ways: By consuming contaminated seafood, or by having an open wound that comes into direct contact with seawater that contains the bacteria. [10 Bizarre Diseases You Can Get Outdoors]

Those who eat seafood contaminated with V. vulnificus, including raw or undercooked shellfish, can experience diarrhea, abdominal cramping, nausea, vomiting and fever, the CDC said.

But if people have a wound that is exposed to the bacteria, as in Funk's case, the bacteria can infect the skin and cause skin breakdown and ulcers. These infections can progress to affect the whole body, and lead to life-threatening symptoms, including dangerously low blood pressure or septic shock, the CDC said.

Once a bloodstream infection occurs, the prognosis is grim: About 50 percent of V. vulnificus bloodstream infections are fatal, according to the Florida Department of Health.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Still, serious illness from the bacteria is rare: the CDC estimates that among the 80,000 people in the U.S. who become sick with Vibrio bacteria per year, about 100 die from the infection.

People are more likely to develop an infection if they have a weakened immune system, particularly from chronic liver disease, the CDC said.

To prevent infection with V. vulnificus, the CDC recommends that people with open wounds avoid contact with salt or brackish water, or cover their wound with a waterproof bandage. To avoid a foodborne illness from the bacteria, the CDC recommends that people do not eat raw or undercooked shellfish.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus