Nicer Up North: Canadians Top Americans in Altruism

SEATTLE — The rumors are true: Canadians are nicer than Americans are, at least if returning lost letters is any indicator of niceness, new research finds.

In a study aimed at measuring altruism, researchers "lost" a total of 7,466 letters in 2001 and 2011 in 63 urban areas in the United States and Canada. In 2001, both countries had similar rates of letter return, the study found.

That changed in 2011, however, when the United States had a 10 percent drop in helping behavior, which did not occur in Canada, suggesting that people in the United States were less altruistic than before, said study researcher Keith Hampton, a professor of media and information at Michigan State University. [7 Things That Will Make You Happy]

The project began after Hampton heard an anecdote that altruism was declining in Canada.

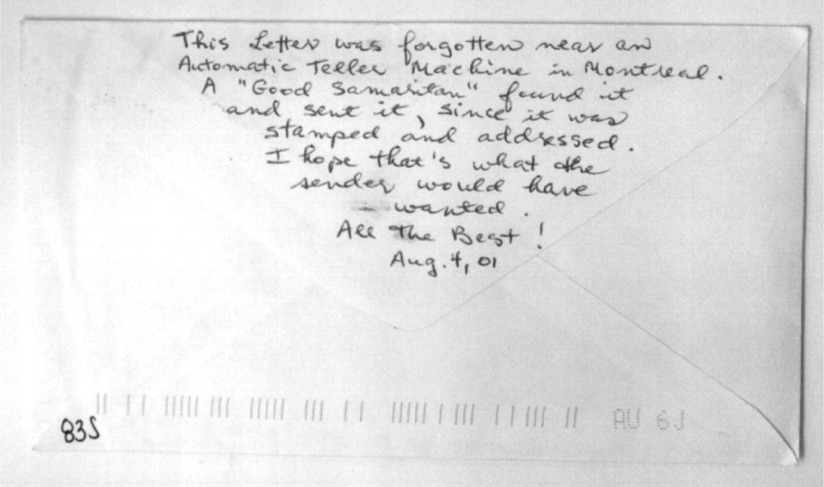

So, he concocted a large-scale "lost" letter campaign, with returned letters serving as a proxy for altruism. Each letter was stamped and addressed, and purposefully lost in a phone booth, store or well-traveled public walkway.

The "lost letter" is a popular technique. The social psychologist Stanley Milgram (1933-1984) developed the method with colleagues to see whether people would help an absent stranger. Studies show that areas where people exhibit more helping behaviors, such as mailing a lost letter to a stranger, are more likely to have lower homicide rates, lower crime rates, fewer teen pregnancies and lower infant mortality, Hampton said.

For the new project, the letters were lost during the daytime in nontouristy areas. The letters were also "lost" stamp-side-up, with an address either for Des Moines, Iowa for the American letters, or Brandon, Manitoba for the Canadian letters.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Snail mail

The 2001 experiment yielded a 59 percent return rate in the United States and a 54 percent rate in Canada, numbers with no statistical difference, Hampton said.

Ten years later, Canada had a 63 percent rate of return, whereas the U.S. had a rate of just 53 percent, Hampton's analysis showed.

It's difficult to say what accounted for the change, but a look a census data provides some potential answers, Hampton said. U.S. poverty and income inequality increased between 2001 and 2011, largely because of the Great Recession, which started in 2008.

In contrast, the recession did not hit Canada as hard, and that country rebounded more quickly than the United States did, Hampton said. Canada also has less income inequality than the United States does, he added.

This suggests that in areas where income inequality is low, there is more altruism, Hampton said. [Top 10 Things that Make Humans Special]

Diversity and altruism

In addition, in Canada, places with higher levels of diversity (that is, areas with more noncitizens and individuals who were foreign born, had immigrated within the past 10 years or visible minorities) had a better likelihood of letter return. The opposite was true in the United States, where people in areas of high diversity were less likely to send lost letters.

This pattern did not exist in 2001, Hampton said. "So, over that time period, something changed in the United States relative to Canada [that was] related to immigration that must have had an impact," he told Live Science.

Perhaps American views toward immigrants changed because of world events and the economy, Hampton said. (The original letter campaign took place before the 9/11 attacks, and, of course, the 2011 campaign took place after the attacks.)

A hypothesis from a 2007 study in the journal Scandinavian Political Studies stated that areas with minorities have less altruistic behaviors, possibly because these minorities hunker down and mind their own business if they feel un-integrated and unwelcome. But immigrants make up a very small minority of these areas with low-letter return rates in the United States, so the immigrants don't account for the areas' overall lower rates of helping, Hampton said.

"More likely, it's the rest of the population that perceives that area as being high in immigrants and is less likely to help them," he said.

Both the United States and Canada have experienced recent surges in immigration, Hampton said. But Canada is known for welcoming immigrants, which may explain why people there mailed more letters, he said.

"There are implications for society as a whole that result from how we treat immigrant groups and [have] income inequality in society," he said. He added that when people are less altruistic, it affects society as a whole, not just the minority groups.

However, there may be more forces at work, said Jason Manning, an assistant professor of sociology at West Virginia University, who was not involved in the study.

"I don't quite understand the speculated causes of it in the presentation," he said. "So, attitudes toward immigrants have become more negative. How does that affect somebody in Omaha, [Nebraska], mailing a letter to Des Moines?"

The research was presented Saturday (Aug. 20) here at the American Sociological Association's annual meeting in Seattle. It is expected to be published in the journal City & Community.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.