7 Home Remedies That Actually Work (and the Science Behind Them)

Folklore remedies

Throughout the ages, people have sworn that odd remedies have cured their maladies. While some of these "treatments" sound outrageously strange by modern standards (such as eating lice to cure jaundice), others can work wonders — at least to a degree.

Almost every culture has some sort of popular home remedy — that is, treatments passed down through the generations by oral tradition, said author and illustrator Carlyn Beccia Cerniglia, who wrote "I Feel Better, with a Frog in my Throat: History's Strangest Cures," (Houghton Mifflin, 2010).

"If you ask anyone of a certain age, they'll say 'Oh, my grandmother used to do that to me,'" Beccia Cerniglia told Live Science. [The Surprising Origins of 9 Common Superstitions]

Here's a look at the science behind 7 home remedies that work, and in some cases, have inspired modern medicine.

(Spoiler alert: Lice don't alleviate jaundice (despite some very specific instructions). According to an ancient Spanish home remedy, people with jaundice were supposed to be fed nine live lice for nine days on an empty stomach, but without the patient's knowledge, according to a 2013 study in the Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine.)

Bedbugs and bean leaves

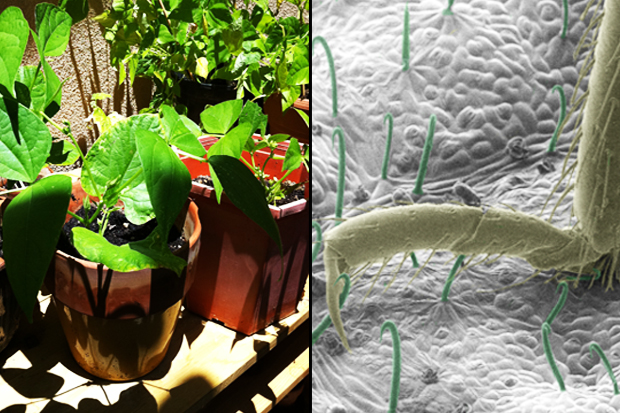

According to a Balkan home remedy, scattering fresh bean leaves around a sleeping area can help kill bedbugs and prevent infestations.

There's some science to the practice, according to a 2013 study in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface. Microscopic filaments on the leaves of kidney beans either impale and kill bedbugs creeping over them, or ensnare the bedbugs' feet, trapping the insects.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers are now trying to make a synthetic version of the bean leaf that will stop bedbugs so people don't have to rely on insecticides or leaves, which stop working once they dry out, the scientists said in a statement.

The above photo shows fresh kidney bean leaves (left) and a zoomed in image (with false color) of the leaves' filaments trapping the leg of a bedbug.

Frogs

According to Russian folklore, it's smart to keep a frog in your milk to keep it from going sour. There's little data on what the frog thinks about this, but there's plenty of evidence that the practice does, in fact, have roots in science.

Amphibians produce antimicrobial secretions that cover their skin, according to the 2012 study, published in the Journal of Proteome Research. This secretion protects the frog against pathogens that thrive in damp places.

A previous study found that Russian brown frogs (Rana temporaria) have 21 substances that show antibiotic activity or medical promise, reported the American Chemical Society. However, the 2012 study dug even deeper and found 76 substances from the frogs' skin that can fight pathogens.

These secretions may have kept harmful bacteria and microbes from spoiling the milk, giving the home remedy credence.

Honey

The ancient Egyptians, Chinese, Indians and Africans used honey to treat a long list of maladies, including ulcers, burns and amputations, according to Michigan State University Alumni Magazine. Today, doctors still use honey to help people recover.

For instance, if a child with a cough is given honey 30 minutes before bedtime, the honey can help make the cough less frequent, less severe and less bothersome, a 2012 study in the journal Pediatrics found.

Furthermore, smearing honey on a wound can help it heal, according to a 1988 study of 59 people in the British Journal of Surgery.

Garlic

Many folklore remedies include garlic, which is actually quite potent, research shows.

For instance, American folklore deemed garlic to be a useful treatment for whooping cough, according to the book "Popular Beliefs and Superstitions: A Compendium of American Folklore (G K Hall & Co., 1981).

But, while munching on a clove probably won't cure whooping cough, a contagious respiratory illness, garlic does have other benefits. Garlic is an antiviral, antifungal and antibacterial weapon, Dr. Andrew Weil, the founder and director of the Arizona Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of Arizona Health Sciences Center, told Live Science in 2011.

Freshly crushed garlic also contains allicin, a compound that can kill some germs on contact, Weil said.

Anti-mosquito plant

A handy way to keep the mosquitoes away is to crush and rub the leaves of the American beautyberry plant (Callicarpa americana) over yourself, according to home remedies in Mississippi's hill country. But although that sounds slightly messy, it actually works, according to scientists at the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The berry contains three compounds that repel mosquitoes: callicarpenal, intermedeol and spathulenol, the researchers found, according to Science Daily.

"My grandfather would cut branches with the leaves still on them and crush the leaves, then he and his brothers would stick the branches between the harness and the horse to keep deerflies, horseflies and mosquitoes away," Charles Bryson, an Agriculture Research Service botanist in Stoneville, Mississippi, told Science Daily.

"I was a small child, maybe 7 or 8 years old, when he told me about the plant the first time," Bryson said. "For almost 40 years, I’ve grabbed a handful of leaves, crushed them and rubbed them on my skin with the same results."

Onions

Onions are found in a slew of recipes for home remedies. The bulb was (falsely) thought to treat health conditions such as boils, hives and convulsions, according to the online archive of American Folk Medicine.

In reality, onions won't help with any of the above, but they are a healthy source of vitamin C, sulfuric compounds, flavonoids and phytochemicals, Live Science reported in 2014.

Phytochemicals are naturally occurring compounds that may protect against cancer, heart disease, osteoporosis and diabetes, according to the Mayo Clinic. Flavonoids give fruit and vegetables their pigment, and may reduce the risk of Parkinson's disease, cardiovascular disease and stroke, Live Science reported.

Ginger

Ginger — a thick, underground stem that looks beige and knotty — can soothe nausea, at least some of the time, research shows. People used to use ginger as a cure-all for colds, stomach aches and menstruation pains, suggesting they had figured out that it was useful in some scenarios. According to a Live Science article, ginger is a safe and effective way to treat nausea and vomiting during pregnancy, preliminary studies suggest. But ginger doesn't appear to be effective when used for motion sickness.

Still, ginger may decrease nausea after chemotherapy treatment, some (but not all) studies report. And it may also help patients who feel nausea felt after surgery, so long as the patient takes the ginger before the operation.

Ginger may also help reduce colon inflammation and ultimately reduce a person’s risk against colorectal cancer, according to a small 2012 study in the journal Cancer Prevention Research.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.