Shock and Awe: Eels Leap to Deliver Electrifying Attacks

In a "shocking" turn of events, a researcher has discovered that electric eels can intensify their electrical attacks by leaping from the water to make physical contact with animals that threaten them, according to a new study.

By elevating their bodies and connecting "chin-first" with an attacker, the eels deliver a more powerful electrical discharge directly into the animal, rather than dissipating it into the surrounding water.

The finding provides support for a famous but previously contested observation of a dramatic interaction between electric eels and horses dating back to 1800. [Video: Electric Eels Leap and Zap To Attack]

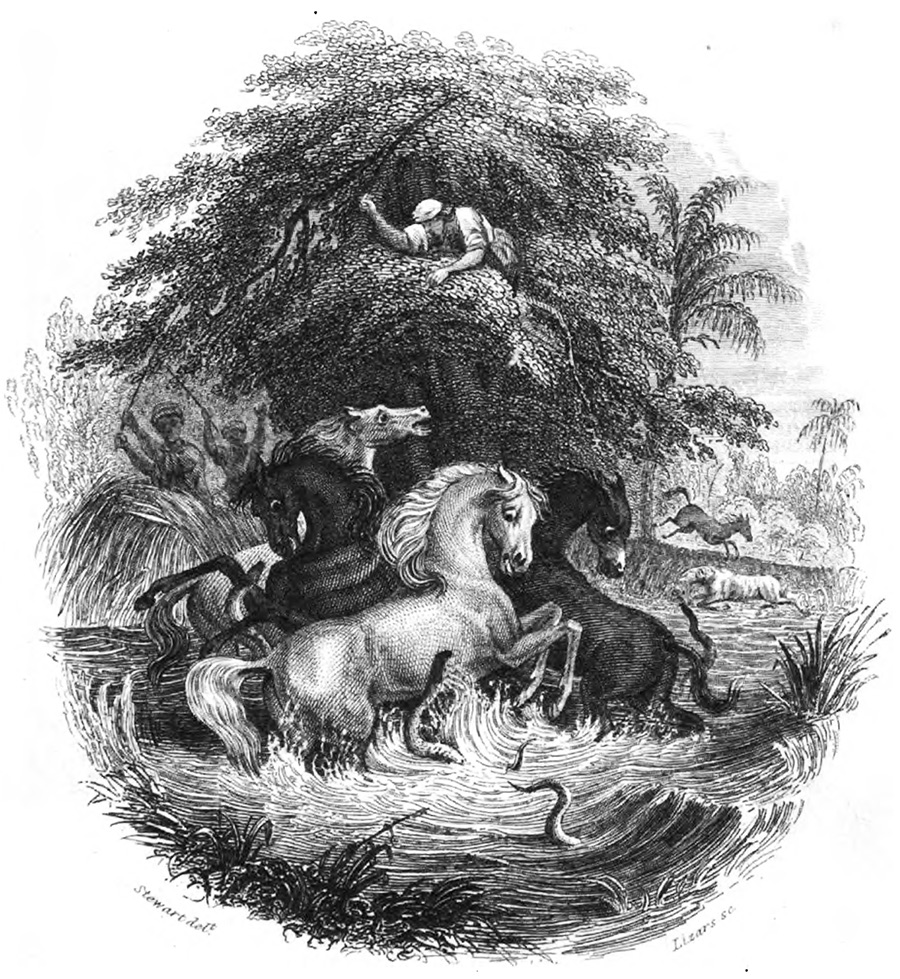

When 19th-century naturalist Alexander von Humboldt set out to collect electric eels in South America, local fishermen introduced him to the concept of "fishing with horses" — herding 30 hapless horses into the eels' pool to sap their electrical charges so the eels could be gathered safely. According to Kenneth Catania, author of the current study and a professor of biological sciences at Vanderbilt University, Humboldt described the eels leaping into the air and pressing themselves against the horses' bodies to repeatedly deliver powerful shocks. Humboldt wrote that two of the horses drowned, while the others collapsed after emerging from the water.

The account made Humboldt famous, though several of his colleagues scoffed at his discovery, referring to it as "poetically transfigured" and, even more harshly, "tommyrot" (i.e., utter nonsense), according to the authors of the new study. It hasn't helped Humboldt's case that, in the 200 years since his work was published, no similar behavior in eels had been observed.

That is, until now.

Shock treatment

Catania reported in the study that the eels' leaps were "serendipitously discovered" during an investigation of their predatory behavior while he was using a net with a metal handle and rim to move them between tanks. As the net approached the eels, they leaped forward and upward, connecting their chins with the net's handle and delivering shocks.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The eels performed this attack "from the outset," Catania said in the study. He suggested that their response differed from other behaviors he had observed because they saw the net as a predator rather than as prey. [Photos: Catch a Glimpse of the Reclusive Glowing Green Eel]

Catania rigged the tanks with equipment to measure the voltage and amperage of the eels as they leaped to attack. He found that when they pressed their chins directly to the threatening target, the eels delivered a more powerful shock than if they had discharged electricity into the water. And by leaping higher, the charge was even more effective; since it had farther to travel before exiting into the water, it affected more of the target's body.

That method made sense as a defensive strategy, Catania concluded. A terrestrial predator could hunt eels while only partly submerged, so it might not be deterred if the eel electrified the water around it. But a direct shock would make a much stronger impression, he wrote.

And during the dry season in the Amazon basin where the eels live, much of the water evaporates, leaving the eels with fewer opportunities to retreat, Catania reported. Leaping out of the water comes with risks, but the shocking offense it lets the eels deliver appears to be their best possible defense.

The findings were published online June 6 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus