Photos: Hidden Text Discovered in England’s Oldest Bible

Biblical history

Hidden text has been discovered beneath one of the oldest printed Bibles in England, one of only seven copies that survives from 1535. Though the Bible is in Latin, the writing is copied from the first authorized English version of the book, providing a hint of how people made the transition from the Roman Catholic Church to Protestantism. [Read more about the hidden text in the 1535 Bible]

Hidden words

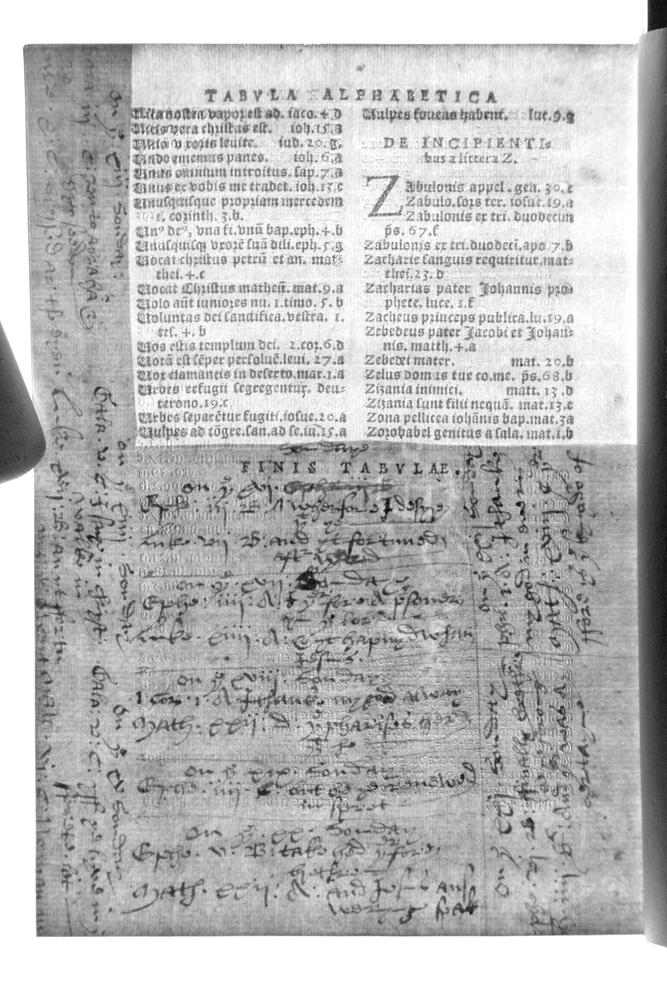

A chance discovery has revealed annotations hidden inside one of the first printed Bibles in England. This handwriting has been covered with paste and paper for more than 400 years. The writing — in English in a Latin Bible — reveals the messy process of the Protestant Reformation in the Henry VIII era.

Latin and English

Printed in 1535 and now held by the Lambeth Palace Library, this Bible was among the first run of printed Bibles in England. It was in Latin, at a time when the Church was splintering in part over whether the scripture should be read in English. By 1539, King Henry VIII would require that the liturgy be performed in English, and the first authorized English-language Bible would be published in England.

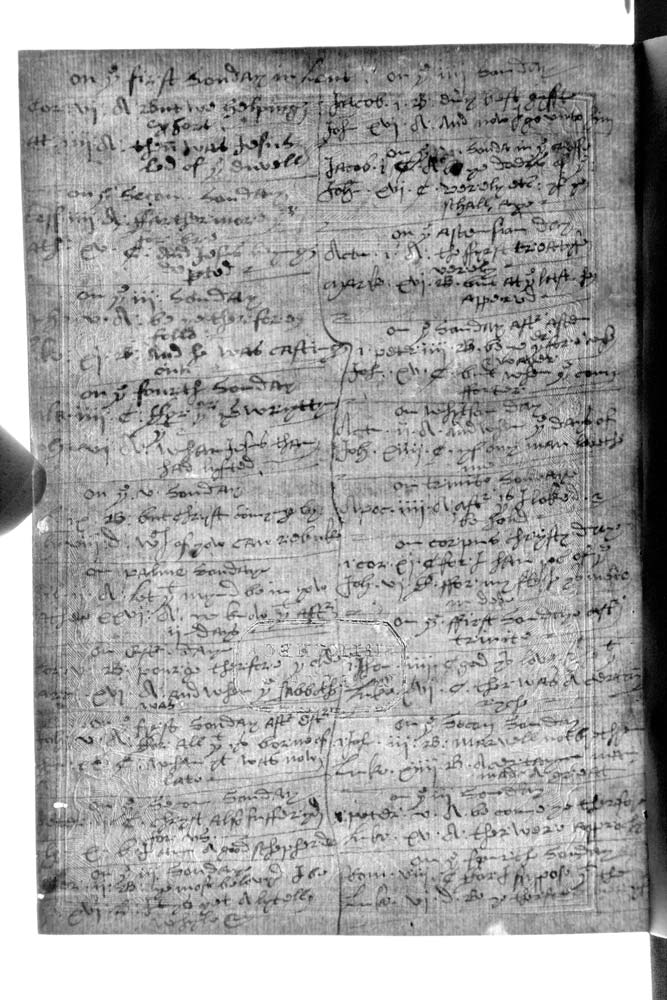

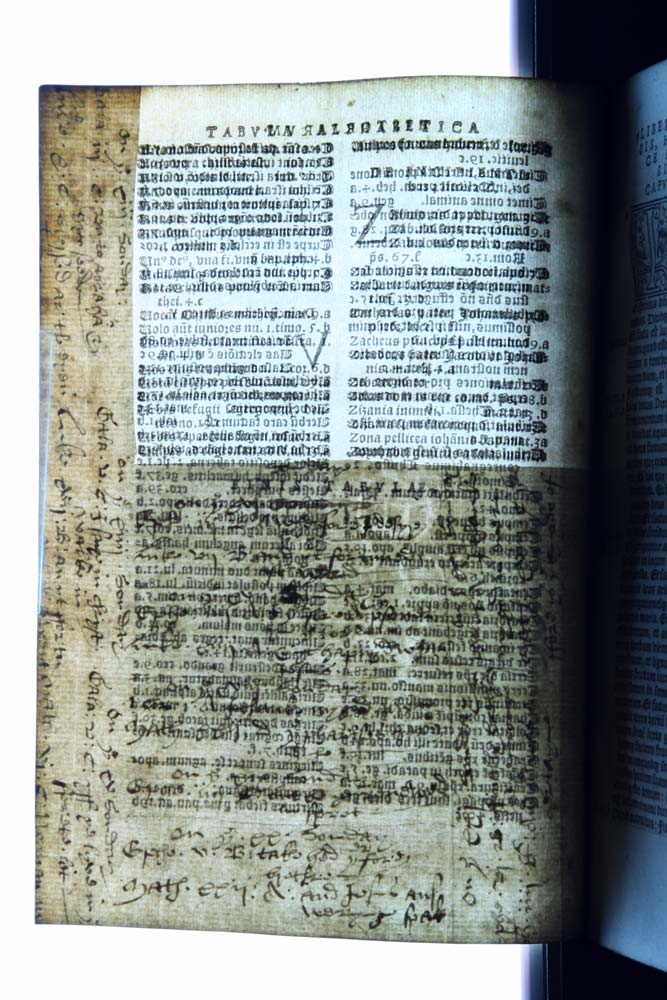

Hidden handwriting

These handwritten notes were jotted in English alongside the Latin text. Eyal Poleg, a historian at Queen Mary University of London, found the notes by accident when he ordered the wrong Bible from a librarian at the Lambeth Palace Library. While waiting for the correct volume, he noticed a small hole in the paper of one of the seemingly blank margins of the book. Handwritten letters were peaking out.

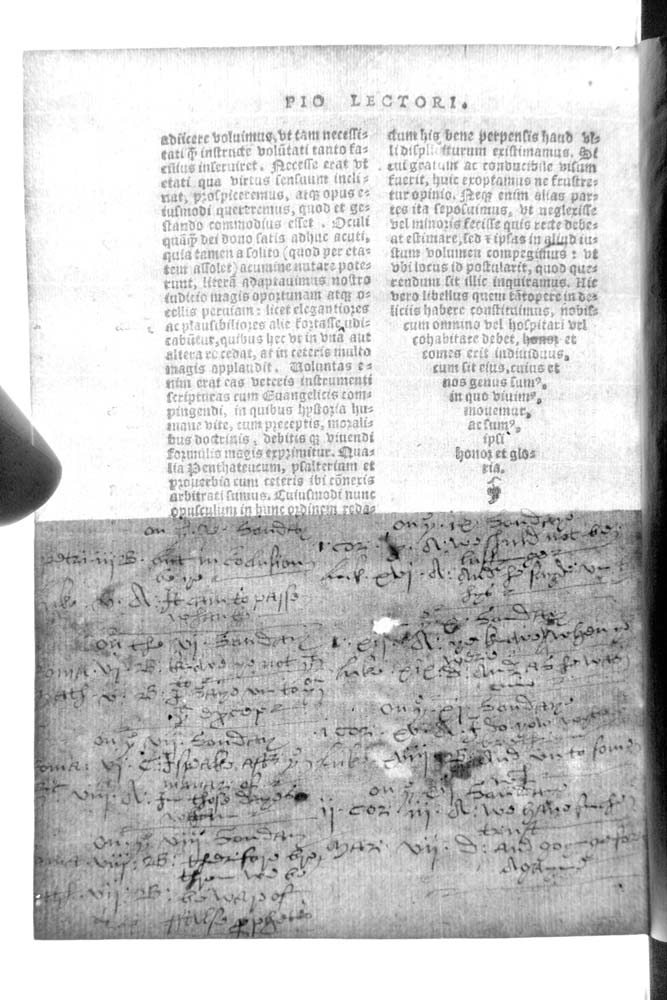

Garbled text

Poleg used a light box, a thin, paper-sized lamp, to backlight the pages, which made the annotations visible. Watermarks on the paper revealed that the pasting-over occurred in about 1600. But because the text on the backside of the pages was also illuminated, it was impossible to read the annotations.

History lurking

A normal-light view of the same page shows how well-hidden the marginalia of the 1535 Bible was. The cover-up was very well-done, Poleg said. It was either done by a bookseller or, most likely, by a Lambeth librarian when the book entered the collections around 1600.

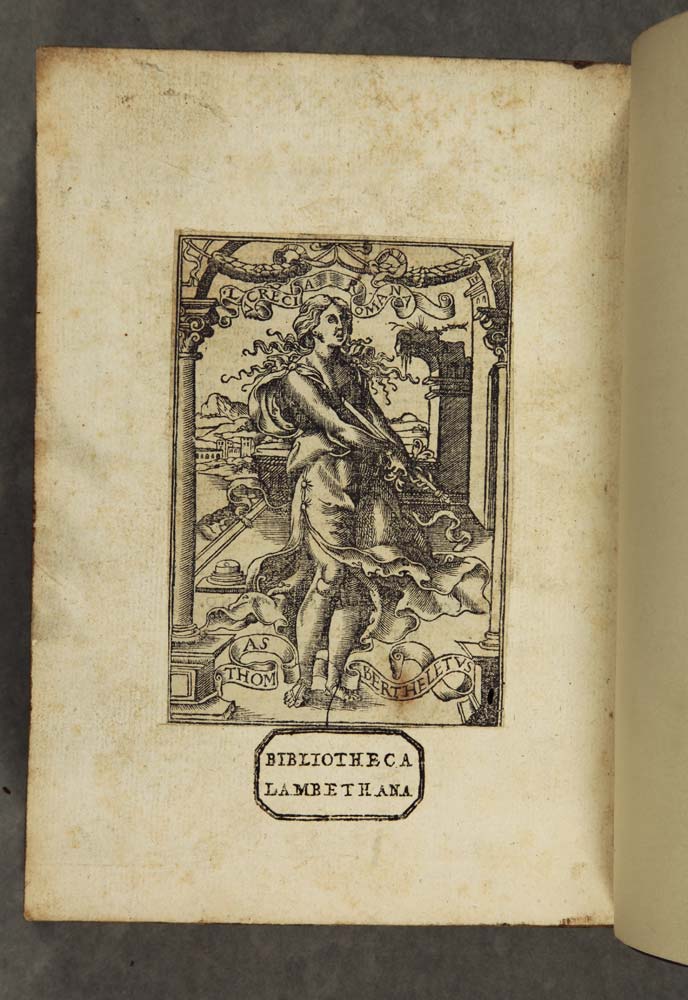

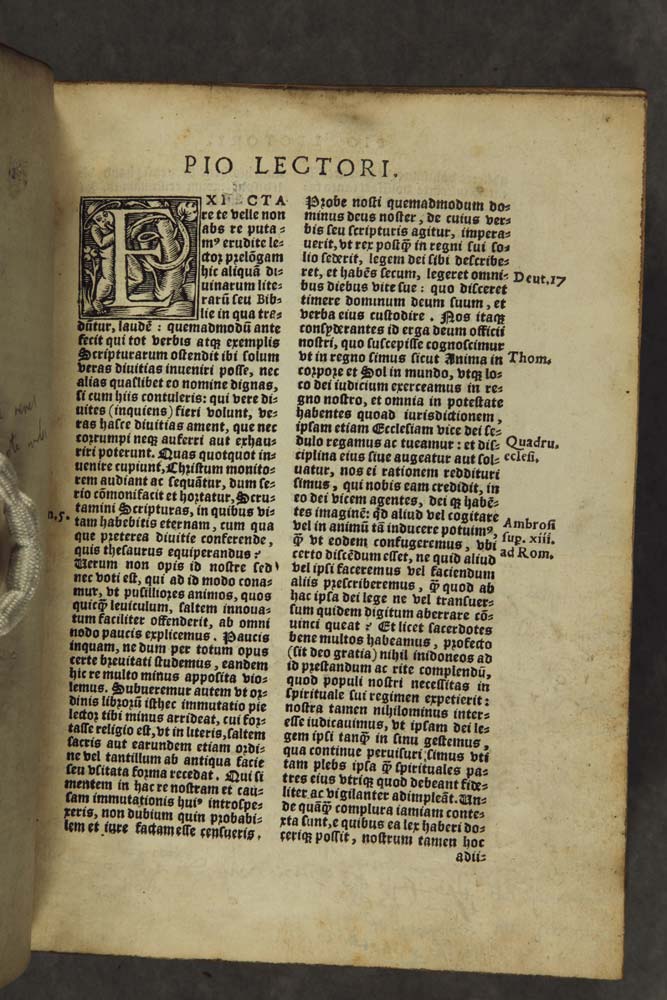

First glance

An illustration in the 1535 Latin Bible, which looks to be a pristine, unmarked copy. Pristine and unmarked books are a disappointment for historians, who use marginal notes to learn how texts were used.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

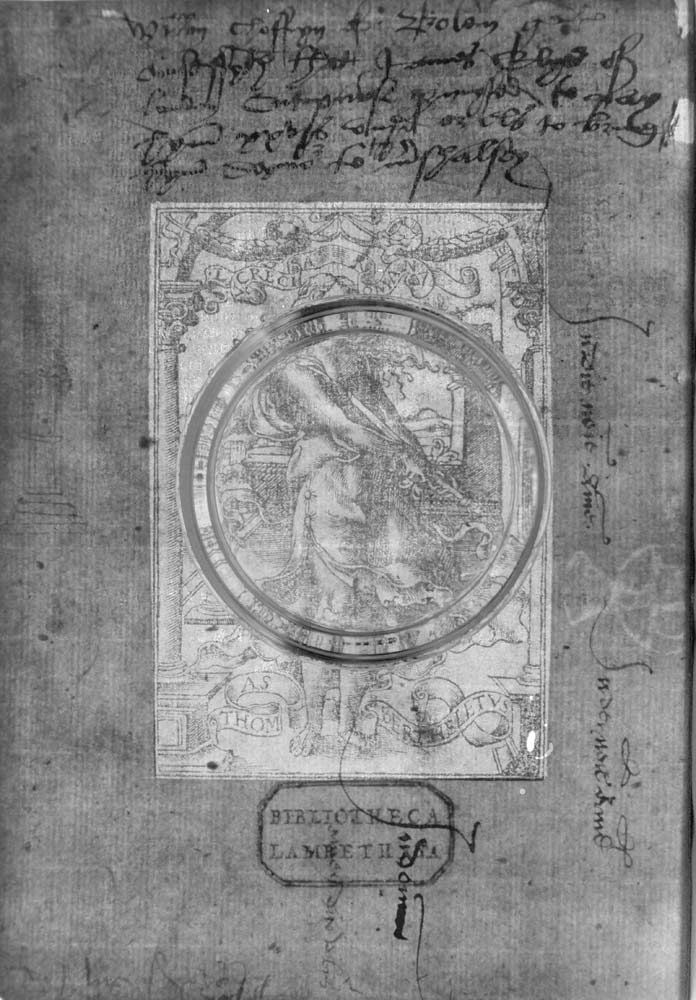

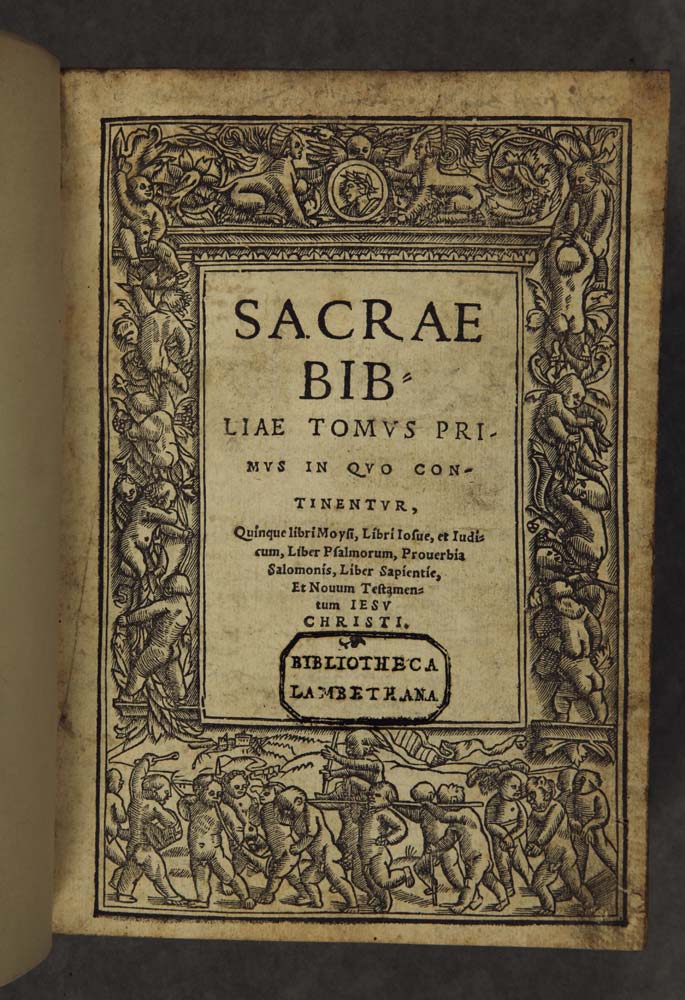

Book by its cover

The Latin title page of the 1535 Bible. The next year, scholar William Tyndale would be executed by strangulation for translating much of the Bible directly from Greek and Hebrew into English. But only a few years after that, King Henry VIII would support the English Bible, and his secretary Thomas Cromwell would commission one that would be printed in 1539. The annotations in the 1535 Bible are copies of the tables of lessons (a sort of liturgical schedule) from this authorized English Bible.

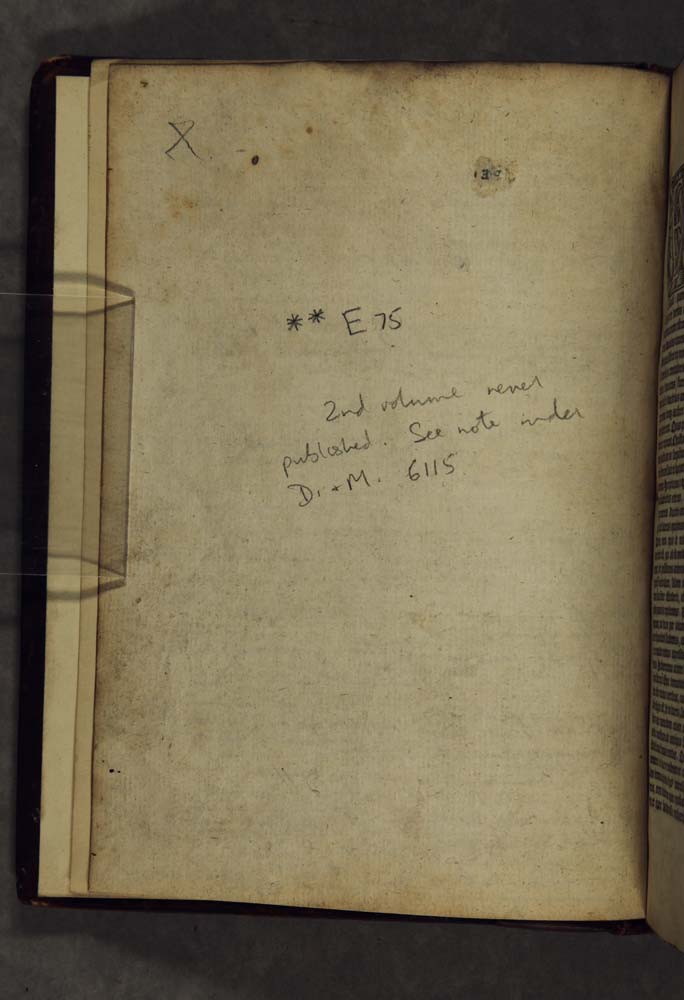

Make a note

Later librarians missed the English annotations, which had been expertly covered with heavy paper. Some even wrote their own notes on cataloguing on top of the covered-up history.

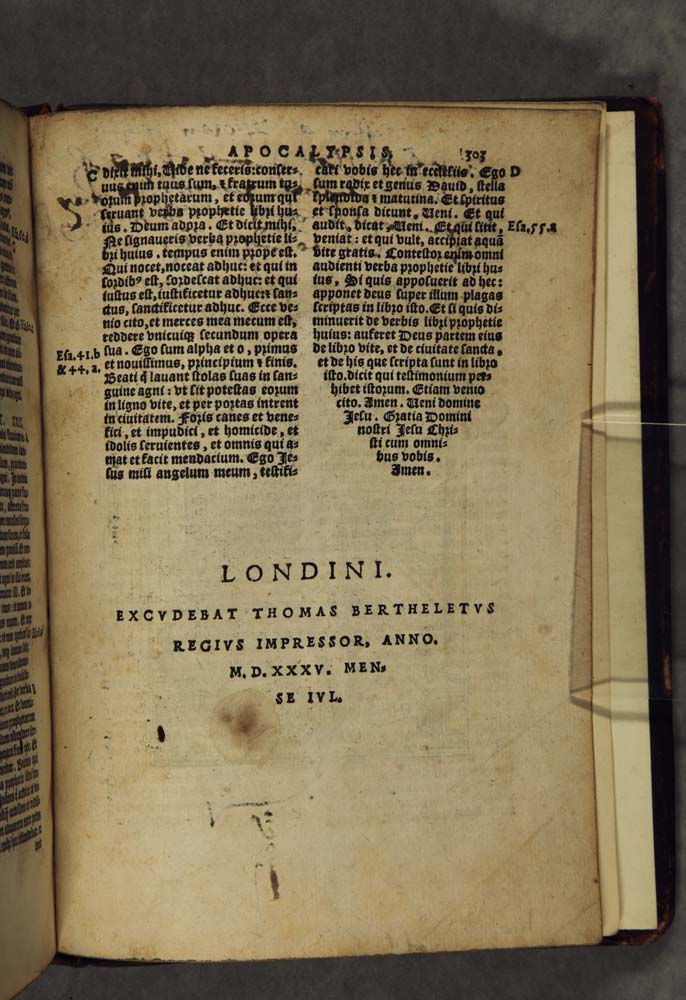

Latin scripture

The seemingly unmarked Latin of a page of the 1535 Bible.

Covered writing

Graham Davis, an X-ray specialist at Queen Mary University of London's School of Dentistry, wrote software to "subtract" the printed text from images of the Latin Bible, leaving behind only the annotations. The method made it possible to read the handwriting for the first time in more than 400 years.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.