Sumatran Rhino Goes Extinct in the Wild in Malaysia

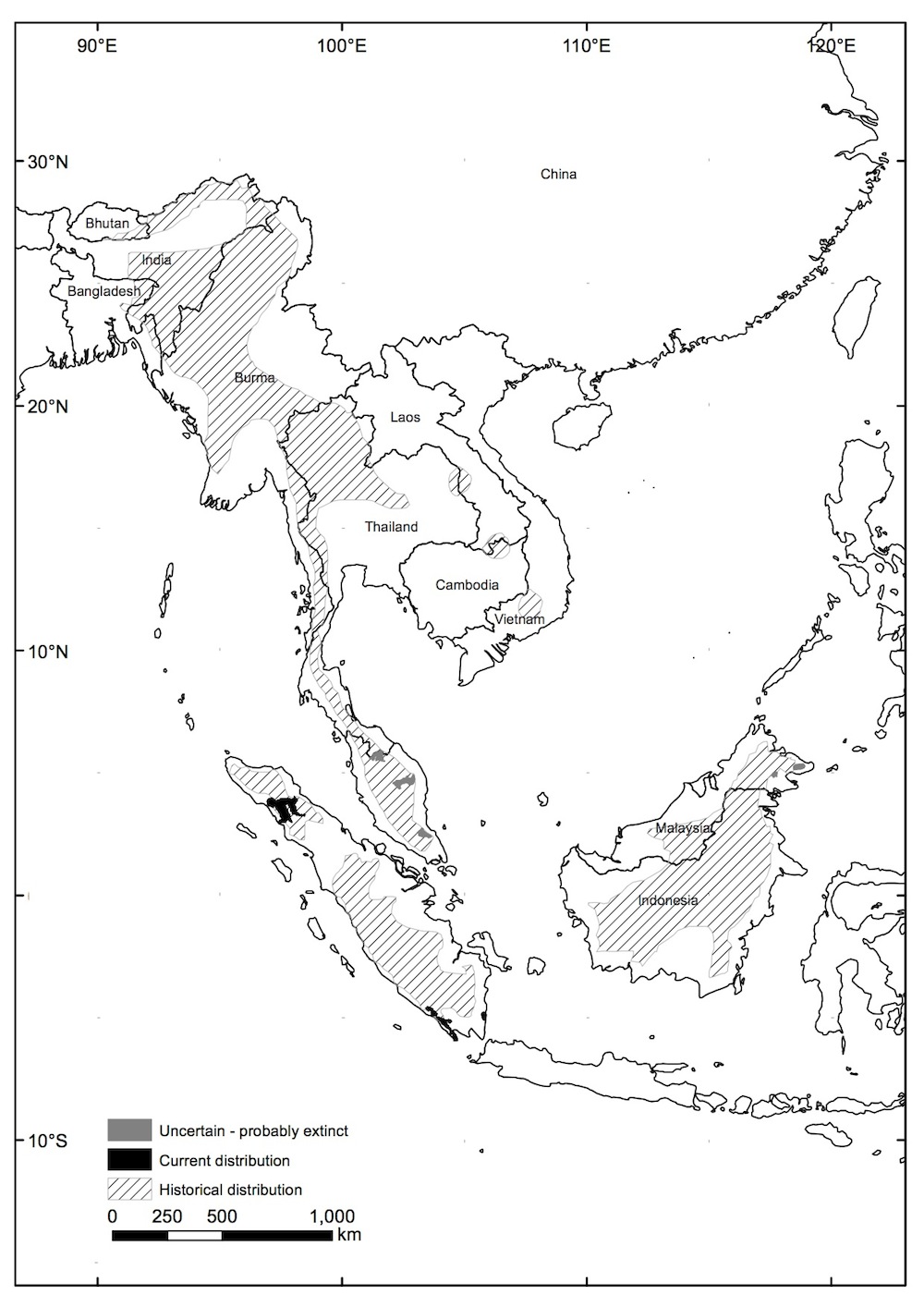

The Sumatran rhino is now considered extinct in the wild in the Southeast Asian country of Malaysia, according to a new study.

No wild Sumatran rhinos (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) have been found on the Malaysian peninsula since 2007, and what are thought to be the last two female rhinos in Malaysian Borneo were caught and placed in captive breeding programs in 2011 and 2014.

Now, fewer than 100 of the species remain in the wild, researchers estimate, distributed among three wild populations on the Indonesian island of Sumatra. [See Photos of All 5 Rhino Species]

In order to save the Sumatran rhino from extinction, it will be necessary to designate the regions where rhinos breed as protected areas, called intensive management zones (IMZs), and to consolidate other, isolated rhinos into these zones to maximize their chances of reproducing, the researchers said. While Asian governments approved the IMZ strategy (along with several others) in 2013, they have yet to be implemented, the scientists wrote in the study.

"We've reached a point of no return," said study lead author Rasmus Havmøller, a graduate student at the Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate at the Natural History Museum of Denmark (affiliated with the University of Copenhagen)."[Sumatran rhino] densities are so low. What we need to do is go out, find out where the rhinos are, firstly, bring them together, secondly, … and then ensure their protection within these areas."

Sumatran rhinos once ranged across most of Southeast Asia, but now Indonesia is the only nation where they breed in the wild.

The rhino's major decline, from both poachingand logging, took place in the 1980s, Havmøller said. Now, the problem is that so few rhinos live in the wild that males and females rarely meet in their native habitats.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Thus they just spiral into extinction by themselves," Havmøller told Live Science. "After being heavily poached and getting into low numbers, it's been the lack of breeding that's the primary cause for their extinction."

A compounding problem is that when female rhinos go for too long without being pregnant, they tend to develop cysts and tumors in their ovaries that may prevent them from carrying a pregnancy if and when they do mate, the researchers said.

In April 2013, at the Sumatran Rhino Crisis Summit in Singapore, rhino experts outlined four strategies for protecting the region's remaining rhinos, which the governments of Indonesia, Malaysia, Bhutan, India, and Nepal agreed upon in the Bandar Lampung Declaration that same year. The new study reviews these strategies, which, the authors argue, must be put into practice to prevent the Sumatran rhino's total extinction.

The first strategy is to manage the remaining Sumatran rhinos not as three separate populations but as one "meta-population." A related goal is to create intensive management zones, the researchers said. Key to the success of these protected areas, Havmøller said, is the ability to capture wild rhinos outside the IMZs, bring them in, move animals from one area to another — to prevent inbreeding, for example — and perhaps, as assisted reproductive technologies in rhinos become more feasible, transport eggs and sperm from one region to another. The animals also need to be able to cross international borders, the researchers added. [Up and Away! Photos of Rhinos in Flight]

The summit attendees also recommended establishing Rhino Protection Units — teams of people, usually including armed park rangers, charged with monitoring the animals, looking for signs of rhinos, and scouting for and arresting poachers — at rhino breeding sites. These units have been established already, but they need to be fortified, by adding more people, running more frequent patrols, and better training unit members, Havmøller said.

The last strategy is to improve captive breeding programs, which currently include nine rhinos. Attempts to breed rhinos in captivity began in 1985; from then until 2001, 45 rhinos in captivity at different breeding sites produced no offspring. Since 2001, four Sumatran rhinos have been born in captivity from two breeding pairs through traditional mating. Scientists are working to add assisted reproductive technologies, such as artificial insemination and in vitro fertilization, to their toolkit in hopes of increasing captive breeding success, the researchers said.

"The political will to actually make this happen is definitely what's the greatest barrier," to putting these strategies into practice, Havmøller said. Managing the remaining Sumatran rhinos as a meta-population would require countries to establish policies for rhino capture and transport among management zones and across international borders he added. Funding is another limitation, the researchers said.

But saving the Sumatran rhino will require governments and other parties involved to make changes quickly because, as the researchers wrote in the study,"the current conservation actions for the Sumatran rhinoceros may not be adequate to prevent the species' extinction."

The research was published online Aug. 3 in Oryx, the International Journal of Conservation.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Ashley P. Taylor is a writer based in Brooklyn, New York. As a science writer, she focuses on molecular biology and health, though she enjoys learning about experiments of all kinds. Ashley's work has appeared in Live Science, The New York Times blogs, The Scientist, Yale Medicine and PopularMechanics.com. Ashley studied biology at Oberlin College, worked in several labs and earned a master's degree in science journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.