A brain circuit that helps create new memories to erase scary ones has been identified, at least in mice.

The circuit connects two brain regions associated with emotion and decision making, researchers said in a new study. Other studies have suggested that these brain circuits operate very similarly in both humans and rodents.

"It translates across species very effectively," said study co-author Andrew Holmes, a neuroscientist at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the National Institutes of Health. "Immediately, we've got an idea of what may be going awry in the human brain in those folks who experience [post-traumatic stress disorder] and anxiety." [What Really Scares People: Top 10 Phobias]

Perpetual fear

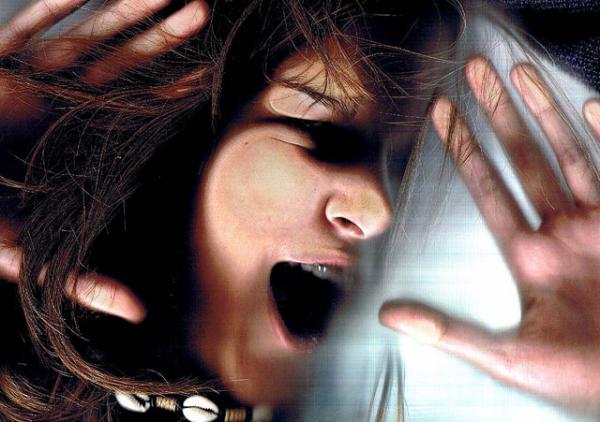

With post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), people who have experienced trauma — such as war, sexual assault or a car accident — may associate a trigger, such as a loud noise or a certain smell, with their past terror. This can lead to flashbacks, anxiety and compulsive thoughts about the terrifying situation. One of the common treatment methods is exposure therapy, in which doctors expose people gradually to the triggers in a safe environment, so that they can "unlearn" their fears. However, exposure therapy doesn't always work, and can sometimes exacerbate PTSD.

Past rodent studies found that mice do better at erasing their fear if they have high activity in a few key brain regions. In particular, scientists zeroed in on the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which plays a role in both decision making and restraining emotion, and the amygdala, which also plays a role in decision making and emotion. By contrast, animals that face the equivalent of rodent PTSD tended to have higher activity in other areas, including in so-called "fear neurons," the researchers wrote in the paper, which was published Friday (July 31) in the journal Science Advances.

The findings led many scientists to propose that the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the amygdala created a kind of fear-killing brain circuit. In this model, overcoming anxiety or the trauma of PTSD isn't just erasing the terrifying memories, but rather creating new, "extinction" memories that serve to overwrite the traumatic ones. Alternatively, the "extinction" memories may act as a kind of mental gate that prevents horrifying or scary memories from being re-experienced, the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Erasing fear

To test out this theory, Holmes and his colleagues used a technique called optogenetics. They injected light-sensitive proteins into mouse brain cells in two brain regions involved in fear extinction. These proteins essentially incorporated themselves into the genes in the brain cells, or neurons. The team also implanted fibers that could shine light on the neurons in those brain regions. When the light shone, the neurons in those brain regions fired. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

Next, they trained the mice to associate a certain sound with a shock to their paws. The next day, they played the same tone 10 times but did not shock the mice's feet. At the same time, the team turned on the "fear-extinction" neural circuit in some of the mice by shining light inside their brains.

Compared to the group of mice without this light-based activation, mice that got a light-based boost to the fear-extinction circuits seemed to form better long-term extinction memories — essentially telling them the stimulus was no longer frightening.

What seemed to be happening was that the brain circuit was "neutrally laying down this new memory — this cognitive reappraisal — that something that was previously frightening was no longer something to be frightened of," Holmes said.

New boost to treatment?

The new results also suggest a way to improve treatment for PTSD in humans, Holmes said.

For instance, a 2012 study in the journal Molecular Psychiatry found that a particular class of brain chemicals called endocannabinoids may play a role in extinguishing fear. (Receptors for endocannabinoids are found throughout the brain and other parts of the body, and marijuana contains numerous chemicals, called cannabinoids, that bind to these receptors.)

Unlike other neurotransmitters (brain chemicals) that are constantly being produced by the brain, endocannabinoids seem to be released on demand, Holmes said.

"They're quiescent until something says, 'OK, we need to activate this circuit,'" Holmes told Live Science. It's possible then, that when someone is reappraising a fearful situation, their brain releases endocannabinoids just in the fear-extinction circuitry and not elsewhere in the brain, Holmes said.

So, in the future, doctors could give patients an endocannabinoid drug just before exposure therapy. The drug would stimulate their fear-extinction circuitry and increase the effectiveness of the exposure therapy, he said.

And because endocannabinoids are released only when they're needed, the risk of unwanted side effects could be lower, Holmes added. Of course, lots of kinks need to be worked out before such methods could be used: showing the same circuits work in humans, identifying a drug that works to selectively activate the fear-extinction circuit and making sure it has no worrisome off-target effects, he said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus