Ancient Volcano Tattooed the Earth with Giant Rings

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

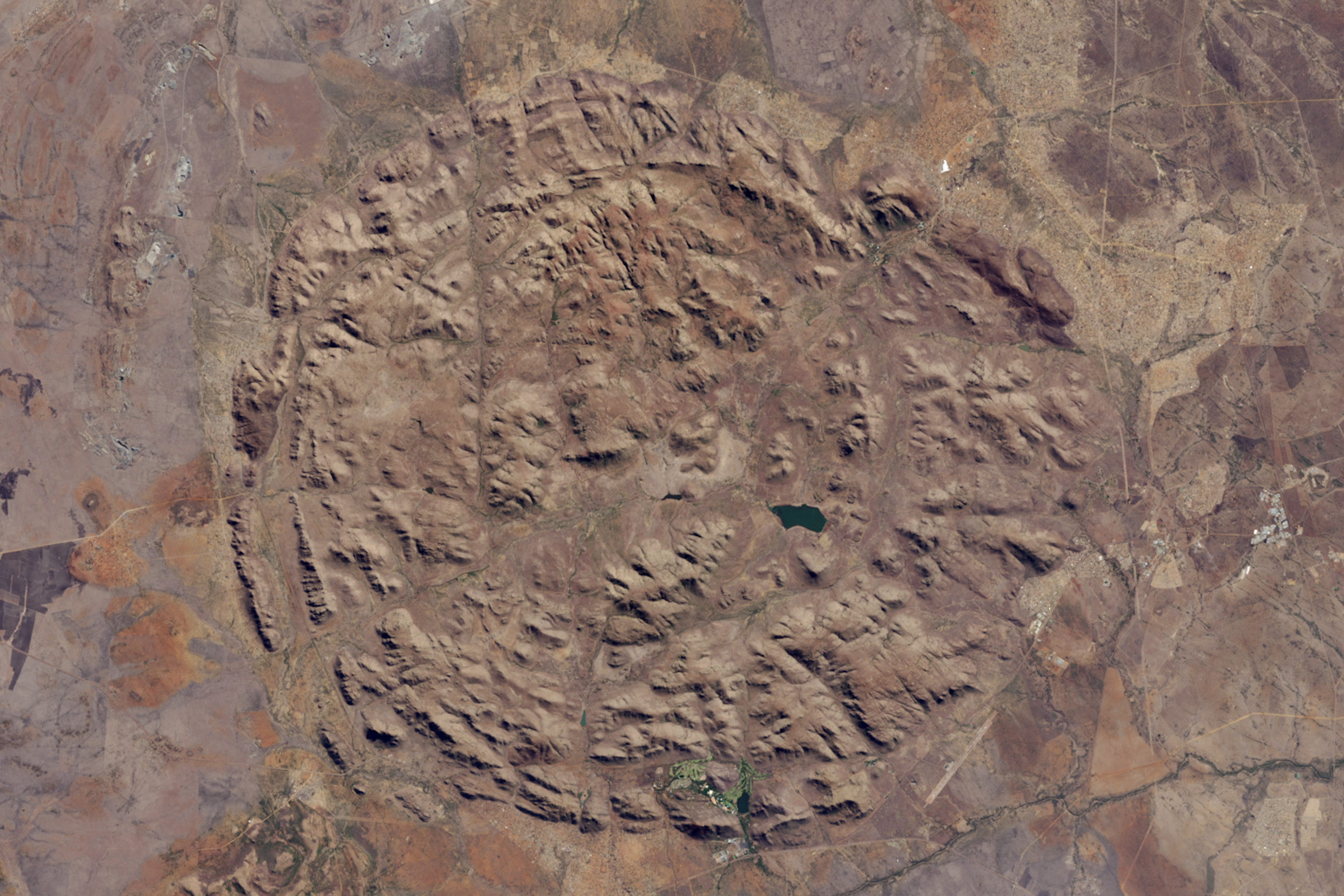

Concentric circles of rocky hills and valleys in South Africa tell the story of a billion-year-old collapsed volcano in newly released photos from NASA.

The circular Pilanesberg caldera is located in the South African province known as North West, in Pilanesberg National Park. The caldera, or cauldron-shaped crater, features different rings of rock that make up a near perfect circle, with structures that rise about 330 to 1,640 feet (100 to 500 meters) above the surrounding landscape. The tallest point, Matlhorwe Peak, soars 5,118 feet (1,560 m) above sea level.

Several streams typically flow through the valleys of these structures, but the Earth-watching Landsat 8 satellite captured the landscape when it was dry, according to NASA Earth Observatory. Man-made dams trap water for the many animals in the region, and Mankwe Lake, the largest body of water in the park, is located in the lowlands east of the center of the rings. [Photos: The World's Weirdest Geological Formations]

The Pilanesberg's story begins about 1.3 billion years ago, when only very simple organisms, like algae, roamed the Earth and volcanoes frequently spewed magma. This molten rock is created in a large pool (called a "hot spot") just below the Earth's crust. When there's enough of the substance, the pressure rises and magma eventually forces its way through the crust, bursting in a shower of fiery, boiling rock, ash and gas.

After the eruption, the ruptured crust collapses into the magma chamber, similar to how skin subsides after a pimple is popped. Magma remaining underneath the crust is propelled upward, just as pus seeps out from under the skin after a pimple bursts, and floods the landscape as lava. The lava then solidifies into volcanic rocks, which can look dark and glassy (obsidian) or grey and spongy (basalt), and can display other characteristics.

Magma that does not make it to the surface as lava cools and hardens, clogging the cracks inside the Earth. These solidified magma formations are called dikes, and in Pilanesberg, many of the dikes are circular because of the circular cracks. As such, these formations are known as ring dikes, NASA officials said.

This cycle occurred many times during this volcano's active period of about 1 million years, according to NASA. Each time new cracks opened, melted magma erupted and formed different rocks. Tectonic activity, or the movement of continental plates, eventually drifted the volcano away from its hot spot, so Pilanesberg is now dormant, according to NASA Earth Observatory.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the millions of years since Pilanesberg stopped erupting, erosion from rain, wind and other natural processes removed the volcanic rocks and exposed the inside of the original volcano and its erosion-resistant ring dikes, which are the strangely circular features seen today.

Ring dikes are not common features, NASA said. Only a few such structures are known in the world, including the Ossipee Mountains in New Hampshire. The Ossipee ring dike formed around 90 million years ago, during the second of three major eruptions throughout the active period of the volcano that created the structure. The original volcano was thought to be around 10,000 feet tall (3,048 m), though the region's current highest peak is Mount Shaw, which rises 3,200 feet (975 m) above sea level.

In the Pilanesberg caldera, a valley that resulted from a crack in the Earth's crust (caused by tectonic activity) cuts from the southwest to the northeast of the ring dikes. Life eventually took over the region's circular hills and valleys, morphing the barren rocks into grassy grazing grounds for elephants, buffalos, giraffes, and white and black rhinoceroses, among other creatures.

Elizabeth Goldbaum is on Twitter. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus