Has Global Warming Taken a Rest? Not So Fast, Study Suggests

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

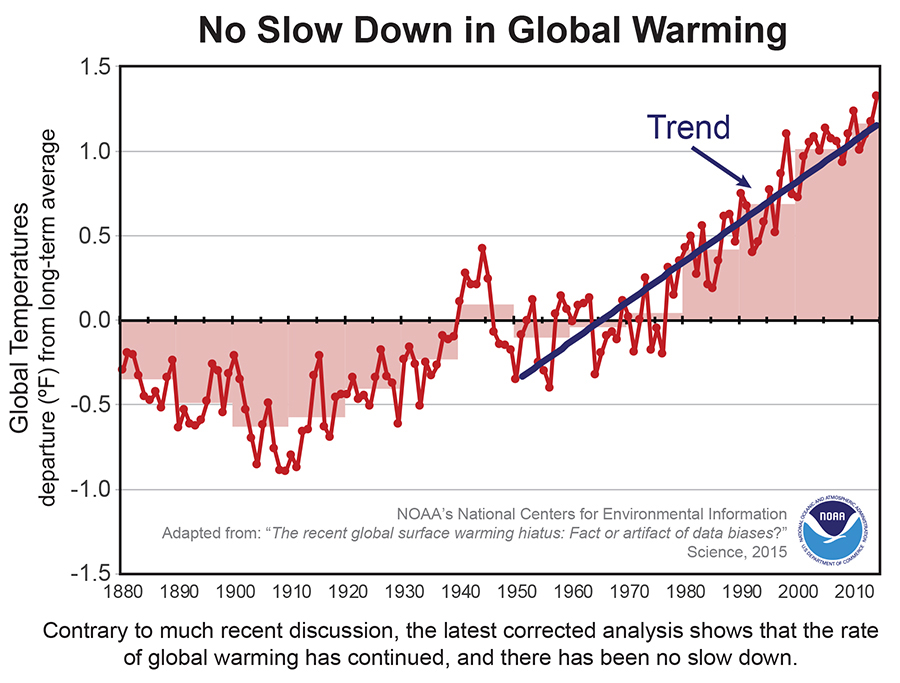

The global warming hiatus — a decade-plus slowdown in warming — could be chalked up to some buoys, a few extra years of data and a couple buckets of seawater.

That’s the finding of a new study published on Thursday in Science, which uses updated information about how temperature is recorded, particularly at sea, to take a second look at the global average temperature. The findings show a slight but notable increase in that average temperature, putting a dent in the idea that global warming has slowed over the past 15 years, a trend highlighted in the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report.

The term “ global warming hiatus” is a bit of a misnomer. It refers to a period of slower surface warming in the wake of the 1997-98 super El Niño compared to the previous decades. However, make no mistake, the globe’s average temperature has still risen over that period (including record heat in 2014) and temperatures now are the hottest they’ve been since recordkeeping began in the 1880s. So let’s call it what it really is: a slowdown, not a disappearance of global warming.

The new findings show that even the concept of the slowdown could be overstated.“There is no slowdown in global warming,” Russell Vose, the head of the climate science division at the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), said. “Or stated differently, the trend over the past decade and half is in line with the trend since 1950.”

- Pacific Winds Tied to Warming Slowdown, Dry West

- Heat is Piling Up in the Depths of the Indian Ocean

- Small Volcanic Eruptions Add to Larger Impact on Climate

Vose helped author the new study, which uses new information about how data is collected at sea to reanalyze surface temperature records. The new analysis essentially doubles the rate of temperature rise since 1998. That puts it more in line with warming trends since the 1950s, though some researchers said there were still some periods of faster warming on record since the 1950s.

Of course this discussion is all centered around changes in hundredths of degrees.

“The fact that such small changes to the analysis make the difference between a hiatus or not merely underlines how fragile a concept it was in the first place,” Gavin Schmidt, the head of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Temperatures have warmed 1.6°F since the 1880s. Projections indicate the temperatures could rise as much as 11°F by century’s end if greenhouse gas emissions aren’t slowed and that the rate of warming could reach levels unseen in 1,000 years by 2030s.

The study was inspired by some new metadata, the data behind the data, that provided clues that scientists weren’t properly accounting for certain types of measurements. Specifically, there have been a proliferation of buoys over the past 40 years and the survival of an antiquated measurement technique used by ships.

Buoys have increased global coverage of the oceans by up to 15 percent since the 1970s, but they have a known cold bias compared to measurements taken from ships.

Another more quirky feature of how global temperature is determined comes from ships. Prior to World War II, the most common way to measure ocean temperatures was dropping a bucket over the side of a ship and scooping up some seawater and dunking a thermometer in.

The process was thought to have pretty much stopped as ships moved to more modern measurements by taking temperatures directly in the water right by their engine intake valves. But the new metadata show that the bucket method is still alive and well and the new findings account for that, something previous analyses haven’t done.

The final piece of the puzzle was the Arctic, which is historically hard to measure given the harsh conditions but is incredibly important to the world’s climate. It also happens to be warming twice as fast as the rest of the globe.

Vose said their new analysis includes updates based on all three of these areas and the result shows warming hasn’t really slowed.

“It is clear that Karl et al., have put a lot of careful work into updating these global products,” Lisa Goddard, director of the International Research Institute for Climate and Society, said. “The impact on our estimates of the trends, especially over the oceans, does seem noteworthy.”

However, Goddard said the results don’t fully show the slowdown has disappeared when comparing the past 15 years to the decades preceding that period and that understanding the natural fluctuations in climate on a year-to-year (or even decade-to-decade) basis provides important context to the warming trends driven by carbon dioxide.Peter Stott, the head of climate monitoring at the U.K. Met Office, agreed, noting in an email that, “The slowdown hasn’t gone away, however, the results of this study still show the warming trend over the past 15 years has been slower than previous 15 year periods.

“My view on this is that the research needs to broaden out to have more of a focus on variability more generally so that a) we can predict the next few years better b) we can refine our estimates of the sensitivity of the climate system to increases in greenhouse gas concentrations.”

Much work has already been done to understand the cause of the slowdown. Some research has tied it to a series ofsmall volcanic eruptions around the globe while other findings have linked it to the changes in winds and ocean circulation.

“The fact that Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said that there’s this hiatus inspired a whole lot of studies,” Vose said. “Here’s why that’s good: a lot of those studies are correct. There probably would’ve been additional warming if those factors hadn’t taken place.”

NCEI is a member of the Fab Four global temperature analysts — the other three being NASA, the U.K. Met Office and the Japan Meteorological Agency — and each uses slightly different techniques to analyze the data but they’re all in general agreement that the planet is warming.

Stott said the Met Office is also refining its estimate of the global temperature and that the new analysis is within the range of uncertainty the Met Office agency includes in its analysis.

You May Also Like: Climate Change Poses a Brewing Problem for Tea The Climate Context for India’s Deadly Heat Wave

Originally published on Climate Central.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus