SAN FRANCISCO — The permafrost in some of Alaska's most iconic national parks could all but disappear this century, new research suggests.

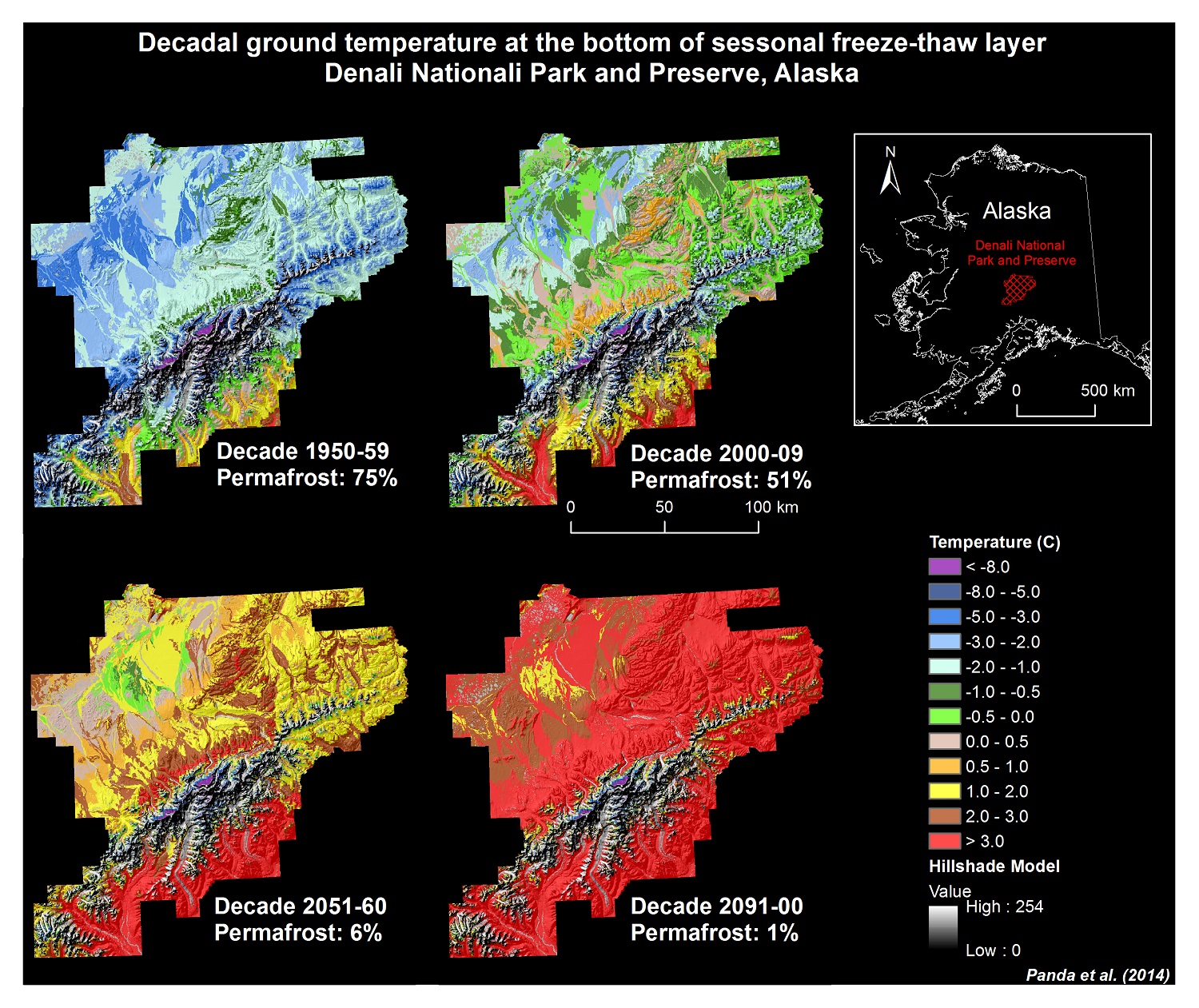

Right now, half of the ground in Denali National Park's is frozen year-round, but if global warming continues at the current pace, just 1 percent of this land could remain permafrost by the year 2100, according to new research presented here at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

Not only could vast swaths of the Alaskan tundra transform into swampy bogs, but the melting ice could release troves of the climate-warming carbon locked beneath the frozen ground.

"If the climate continues to warm as it has been for the last 30 or 40 years, permafrost will degrade, and only in a few pockets will you have permafrost," said study co-author Santosh Panda, a permafrost scientist at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. ['Street View' Images of Denali National Park]

Melting arctic

Though human-caused climate change is affecting the whole world, dozens of studies have documented that the Arctic is warming faster than the rest of the planet. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has predicted that most of the permafrost in the Northern Hemisphere will disappear this century. Many of the current models predict that the climate in the Arctic will warm by 7 to 9 degrees Fahrenheit (4 to 5 degrees Celsius) by 2100, Panda told Live Science.

But Panda said one study found that the climate models that the IPCC uses are good at predicting temperature and precipitation changes in some areas, and not so good in others. So his team looked specifically at five of the 30 climate models that perform well in Alaska.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

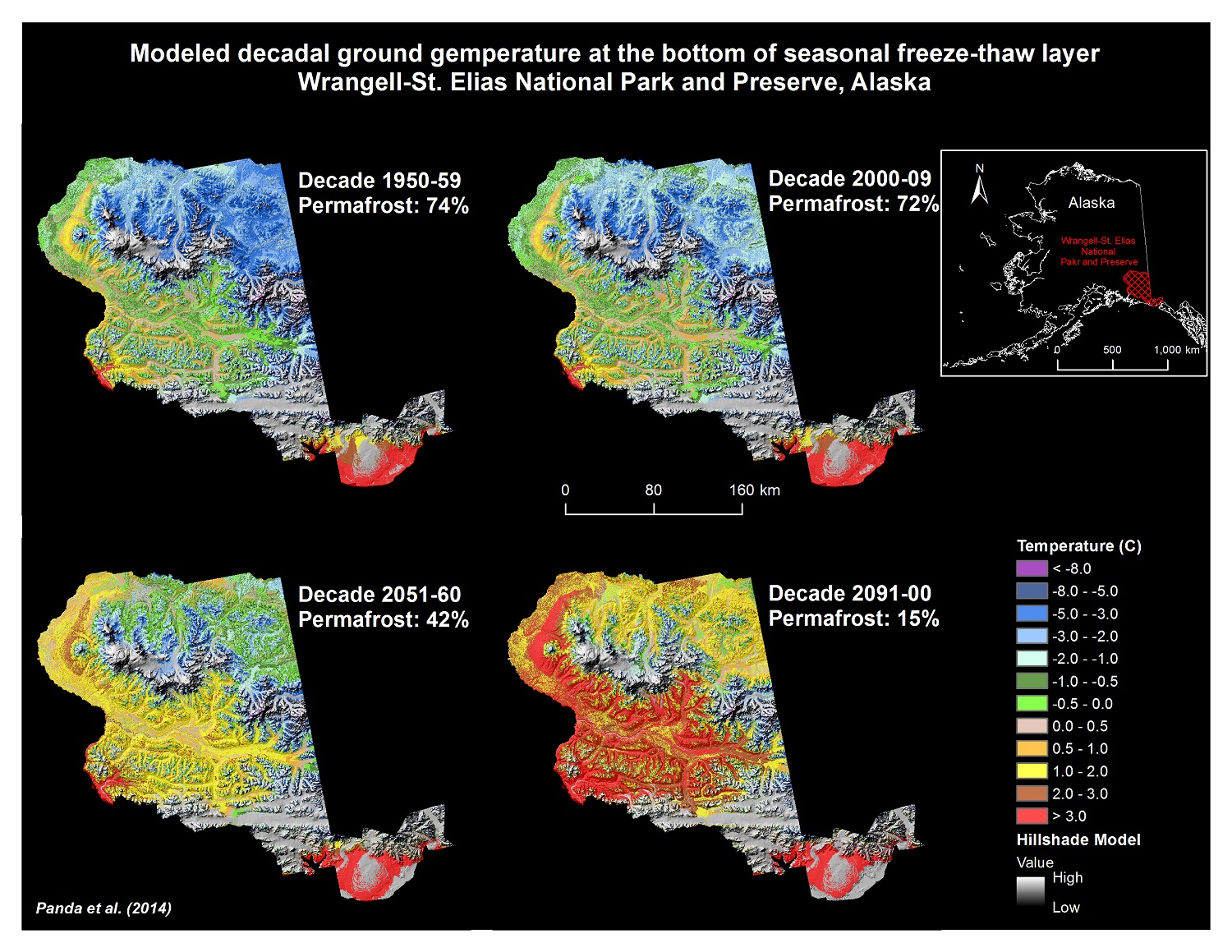

The team used those models, along with data on the type of soil and ground cover in regions throughout Alaska's eight national parks, to model the change in permafrost over time. Clay, sand and silt have different thermal properties, so the ground's composition may determine how well it is buffered from warming air temperatures.

Ground cover can also make a big difference. Moss, for instance, helps to buffer permafrost against thawing, because it insulates the frozen ground from the warmer air in the summer, and conducts heat from the ground to the air when it freezes over in the winter, Panda said. In contrast, spruce forests aren't as likely to insulate the permafrost soils that they grow in from warming temperatures, he added.

National parks

Panda's team found that the vast majority of permafrost in Denali National Park in central Alaska will disappear by the 2090s, with only tiny bits clinging to the higher-altitude mountaintops, where the air is colder. Farther south, in Wrangell-St. Elias Park and Preserve, nearly three-fourths of the ground is permanently frozen today. But by the 2090s, just 15 percent of the permafrost will remain.

This massive Arctic melting could wreak havoc on the state's infrastructure, which is built on frozen ground. As the Earth thaws, the water will seep out of the ground, and some portions of the ground will collapse, Panda said.

If the Arctic permafrost were to thaw, it could transform much of the ground into swampy peatland, potentially devastating some of the creatures that had adapted to live on the frozen tundra.

In addition, scientists estimate that 800 gigatons of carbon are locked in the top 10 feet (3 meters) of the Northern Hemisphere's permafrost, Panda said. If the climate continues to warm, that carbon could be released into the atmosphere, fueling a vicious cycle.

"We are already in that loop," Panda said. "If the climate continues to warm, then that loop will continue to get more and more intense."

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus