Autopsies from Space: Who Killed the Sea Lions?

This article was originally published on The Conversation. The publication contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

A decade ago, we set out to unravel deep ocean crime scenes we weren’t even sure existed. The crime? Endangered Steller sea lions were rapidly disappearing in parts of Alaska. Their numbers dropped by 80% in three decades, yet only rarely did anyone see or sample dead sea lions. Live sea lions studied in the summer when they haul out to breed seemed healthy and had healthy pups.

We wanted to know when, where, and why sea lions die. To unravel the mystery, we needed information from those animals that we don’t see, those that might not breed, those that might never come back ashore. So we developed a special monitoring tag that could send us data about the sea lions we can’t directly observe.

This so-called Life History Transmitter or LHX tag is a small electronic monitor surgically implanted into the gut cavity of young sea lions under anesthesia. Don’t worry, we checked that this does not alter the behavior or survival of the animals. After all, we don’t want to influence the data we need!

A tag monitors the host animal throughout its life. After the host dies, tags are freed from the decomposing, dismembered or digested carcass. They float quickly up to the ocean surface and begin to transmit previously stored data to orbiting satellites. No matter where these sea lions go, we eventually get a sad email that confirms one of our study animals has died. Since tag data is relayed by satellites, we call these “autopsies from space.”

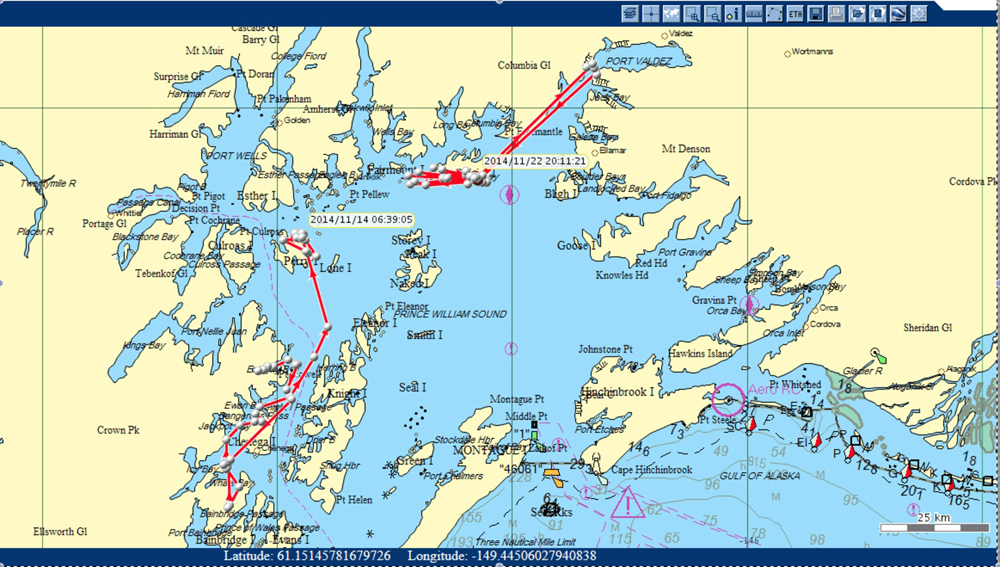

Since 2005, we’ve placed tags in 45 young sea lions in the Prince William Sound area of the Gulf of Alaska. So far, 17 of these sea lions have died. That’s actually about how many deaths we expected. Young sea lions have a tough life and most don’t even reach the age of reproduction.

In two cases, we did not receive enough data to conclude how these sea lions died. Tags from the other 15 sea lions did give us complete data sets. As it turns out, these 15 animals died at sea. Much to our surprise, all 15 apparently died from an attack by a predator. How can we tell?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

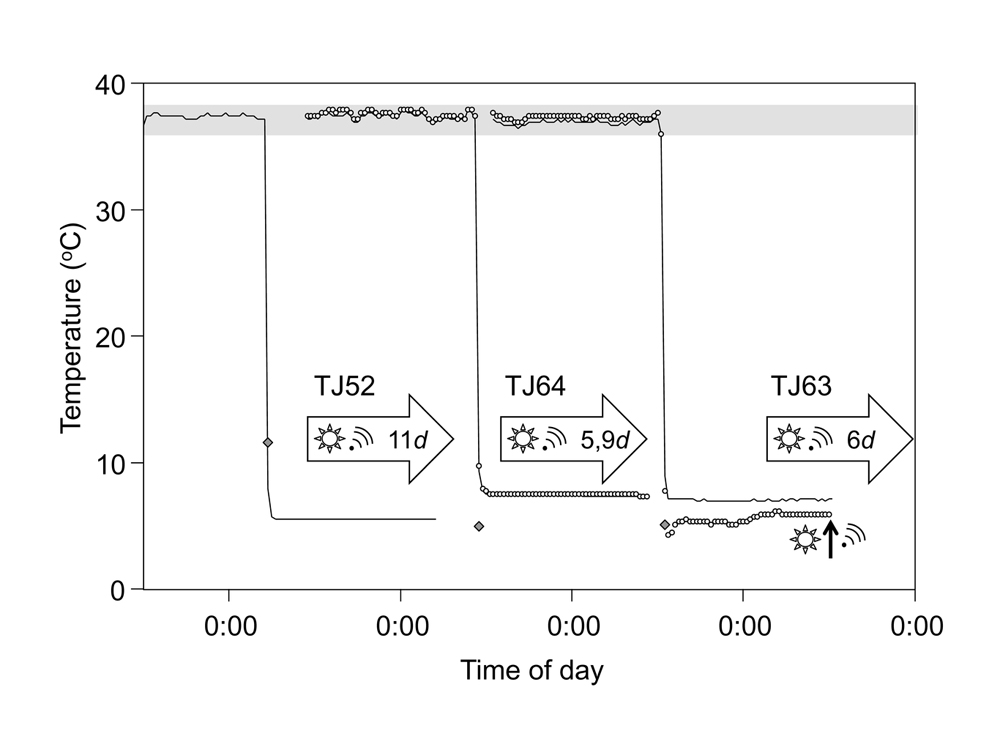

LHX tags record temperature and light levels. They can also distinguish between being surrounded by tissue, saltwater or air. The data we received via satellite from the first few “crime scenes” all followed the same pattern: the tags very quickly cooled from 98F (37C), the normal body core temperature for a healthy warmblooded animal like a sea lion, to the temperature of the ocean surface at time and place of the attack. At the same time, the tags sensed light and air, and began to transmit. Pretty much the only way this could happen is if the sea lion was dismembered by a predator and the tag came flying out.

We could only guess who might have done this: killer whales, white sharks, salmon sharks and maybe sleeper sharks have all been reported as predators of sea lions. Killer whales are considered the most common predator, but that could simply be because killer whale attacks – which happen near the ocean surface – are more likely to be observed than other attacks that may occur at depths as deep as 500m, the deepest known dive for Steller sea lions.

More recently however, three of our “autopsies from space” revealed some puzzling patterns: tags still recorded rapid temperature drops, but they remained in the dark and didn’t sense any air. Even more baffling, the temperatures they recorded after the attack did not match ocean surface temperatures. Instead, the temperatures corresponded to deep water values. These tags only sensed light and air, and surface temperatures, anywhere from five to 11 days later. That’s when they began to transmit. What was going on?

We think these tags were swallowed by a cold-bodied predator and passed or regurgitated a few days later. This eliminates killer whales from the suspect list for these three attacks, since they are also warmblooded. Even white and salmon sharks have the ability to raise their body temperature well above ambient. This leaves the sluggish, slow-moving, poorly understood and truly cold-blooded Pacific sleeper shark as our prime suspect.

Why is this important? To promote the recovery of Steller sea lion populations, fishing has been restricted in some regions of Alaska. These regulations are based on the assumption – not backed by hard evidence – that sea lions are suffering from lack of food. When people take less fish, there’s more left for the sea lions. However, sleeper sharks are killed as bycatch in many fisheries. So one unintended consequence of fishing restrictions may be more sleeper sharks in the sea. Counterintuitively, these measures meant to help sea lions by preserving more of their food might be hurting them by leaving more predators to eat them.

Piecing together all the clues from our sea lion crime scenes, we’re confident we’ve narrowed in on one of the suspects. This investigation is not about bringing a killer to justice, but our new understanding of the crime might affect future fisheries management decisions.

Markus Horning receives funding from the National Science Foundation, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the North Pacific Research Board, the Pollock Conservation Cooperative Research Center, the North Pacific Fisheries Foundation. This research was authorized under all required institutional and federal permits under the Marine Mammal Protection Act and Endangered Species Act, including NMFS #1034-1685, 1034-1887, 881-1890, 881-1668, 14335, and 14336.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus