Itty-Bitty Algae Create Colorful Currents Near Namibia

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

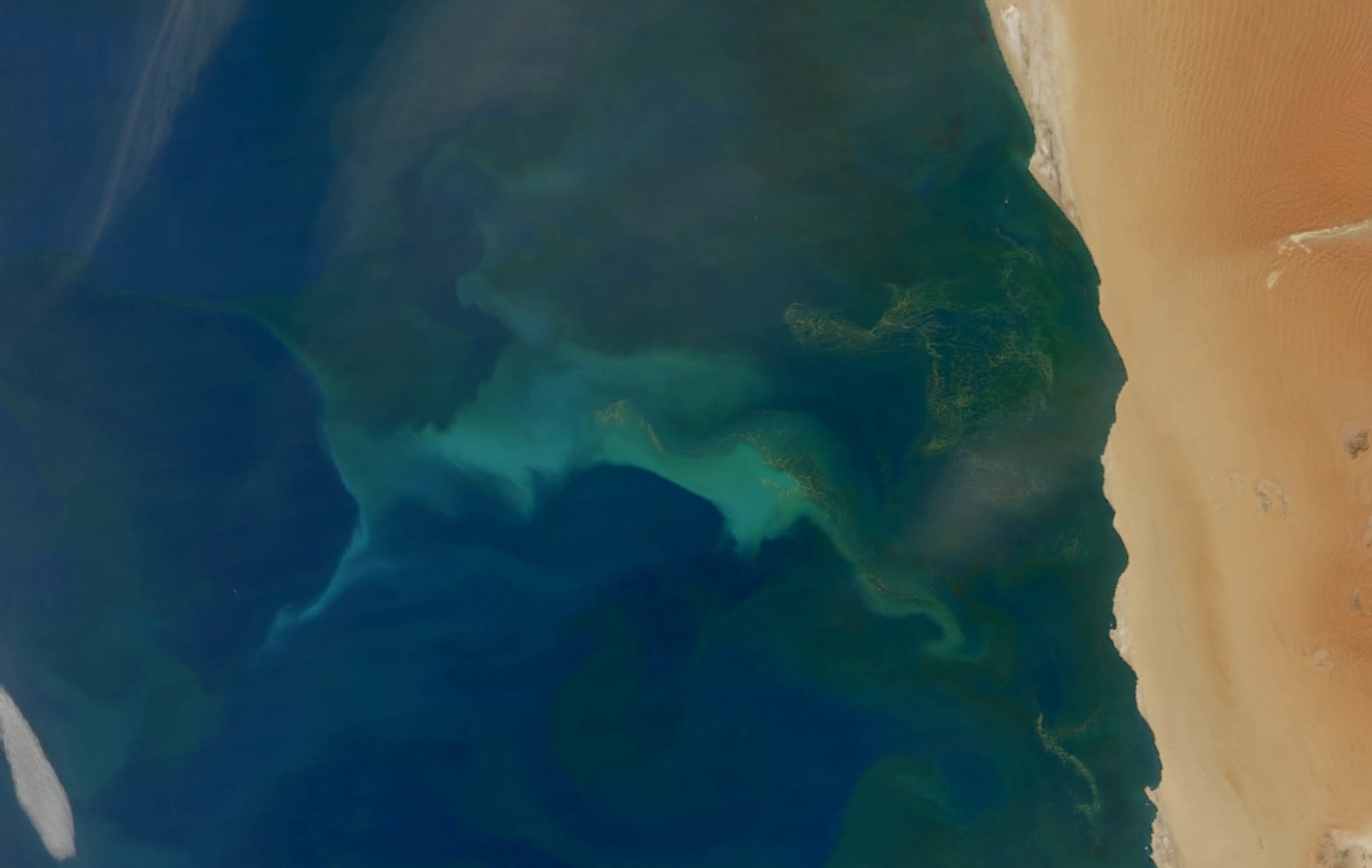

A new satellite photograph of the coast of Namibia shows the ocean in full color — "dyed" green and yellow by microscopic organisms.

The green swirls are masses of phytoplankton, single-celled plantlike organisms that convert sunlight to energy. The growth of phytoplankton is encouraged by the winds and currents along the southwest coast of Africa, according to NASA's Earth Observatory. Winds from the East push surface waters toward the open ocean; as a result, deep ocean water rises, a process called upwelling. This cold, nutrient-rich water feeds a thriving ecosystem, the bottom rung of which is phytoplankton.

Upwelling occurs in many places in the open ocean and along coasts, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Another notable upwelling spot is off the California coast.

Close to the shore in this image, yellow tendrils may be sulfur from bottom-dwelling bacteria, according to the Earth Observatory. Bacteria in the oxygen-poor deep release this sulfur, according to a 2009 study in the journal Progress in Oceanography. Unfortunately for any fish caught in the way of these releases, hydrogen sulfide is very poisonous. It's known as "swamp gas" or "sewer gas" and smells like rotten eggs. The toxin affects the respiratory and nervous systems, and high exposure can lead to rapid respiratory arrest and death.

That means natural hydrogen sulfide releases like those off the coast of Namibia may be fatal to larval or juvenile fish, researchers wrote in the 2009 Progress in Oceanography study.

"The area of the shelf prone to anoxic [no-oxygen] and sulphidic conditions is the nursery ground favoured by commercially important stocks such as pilchard (Sardinops sagax), horse mackerel (Trachurus trachurus capensis), and Cape hake (Merluccius capensis)," the researchers wrote.

If little bacteria can cause such big havoc, perhaps its no surprise that their byproducts are also visible from space. The new image comes from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (MODIS) on NASA's Aqua satellite, which swooped over the Namibian coast on April 10.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Namib desert, visible on the right of the image, is an amazing place in its own right. The desert is famous for its weirdly barren "fairy circles," patches that may be caused by termites.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus