What a Gas! Arctic's Ozone Hole Looking Good

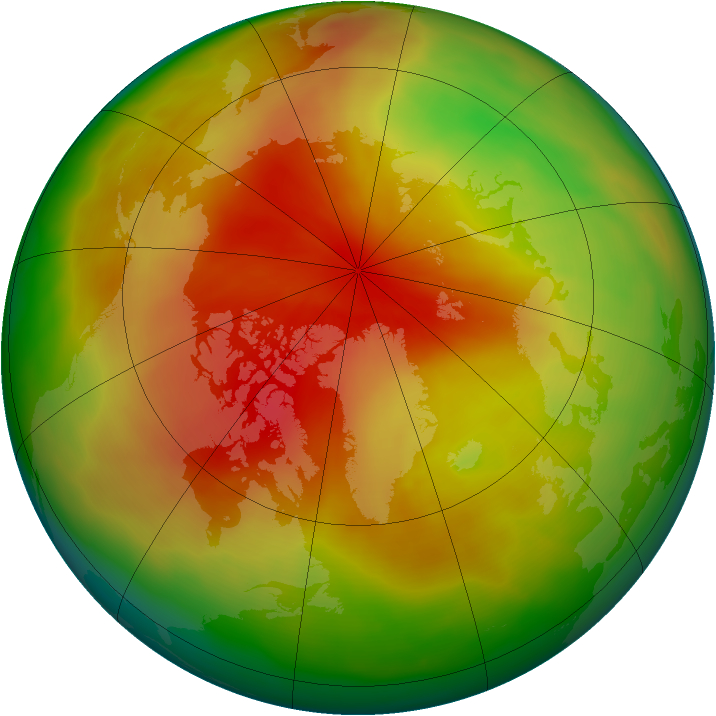

With a boost from Mother Nature, the worldwide ban on ozone-depleting chemicals stopped Arctic ozone from disappearing and forming an "ozone hole" similar in size to Antarctica's, a new study finds.

"It seems like we did just the right thing at the right time," said Susan Solomon, an atmospheric chemist at MIT and lead study author. "It's quite a success story."

Looking back at some 50 years of Arctic ozone records, Solomon and her co-authors found no evidence that Arctic ozone levels have dropped to the extremes seen above Antarctica. Though described as a "hole," the area over Antarctica actually represents the partial to complete disappearance of Earth's protective ozone layer. This protective ozone layer has yet to vanish above the Arctic.

But it turns out that Arctic ozone is protected by more than just environmental limits, the study also finds.

Natural differences between the Arctic and Antarctica, including warmer temperatures over the Arctic, different geographies and different sunlight amounts, kept ozone above the North Pole from disappearing as quickly it did above the South Pole. [North vs. South Pole: 10 Wild Differences]

"The main difference is a few degrees of extra cold temperature," Solomon told Live Science. "Antarctica really is the coldest place on Earth. The few degrees of extra cooling make a big difference in how effectively you destroy ozone."

The findings were published today (April 14) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ozone in the stratosphere helps block damaging ultraviolet-B (UV-B) radiation from the sun. The stratosphere is the layer of Earth's atmosphere above the one humans live in, which is called the troposphere.

The ozone-destroying chemicals are chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), banned in 1987 by the Montreal Protocol. Manufacturers had used CFCs in aerosols like hairspray, as well as in air conditioners, refrigerators and cleaning solvents.

Researchers confirmed the link between the recurring Antarctic ozone hole and CFCs in the early 1980s. The chemicals linger for decades in the atmosphere, slowing recovery of ozone, which is constantly made and destroyed in the stratosphere. Chlorine from CFCs tilts this chemistry more toward destruction.

Solomon and her co-authors compared how CFCs attack protective ozone in different layers of the atmosphere above the Arctic and Antarctica. One of the biggest Arctic ozone losses in 30 years, in 2011, sparked the study. Unusually cold temperatures in the Arctic drove that loss.

The researchers compared the 2011 Arctic extreme to conditions in Antarctica, and also looked at ozone data extending back to the 1960s.

The lowest ozone concentrations occur when air temperatures are minus 112 degrees to minus 121 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 80 degrees to minus 85 degrees Celsius), the researchers found. These extremely cold temperatures are closely linked with low nitric acid levels in the air, a key step in the chemical chain that destroys ozone, the study shows. And such bitter cold is much more common above Antarctica.

"You just don't get down to these cold temperatures in the Arctic," Solomon said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.