Cause of Odd Arctic Ozone 'Hole' Found

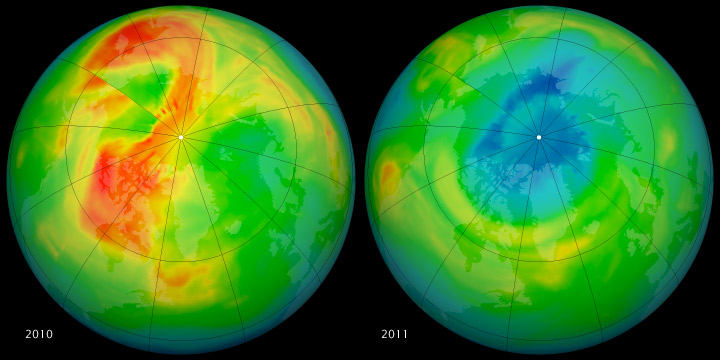

Cold temperatures, chlorine and a stagnant atmosphere caused a thinning in the ozone layer over the Arctic in 2011, a new NASA study finds.

This ozone loss is not the more famous ozone hole, found seasonally over Antarctica, which has been shrinking since the phase-out of chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, that interact with ozone molecules in the atmosphere. These ozone molecules are made of three oxygen atoms bound together. Their high concentration in the stratosphere about 12 miles to 19 miles (20 to 30 kilometers) above the Earth's surface blocks harmful ultraviolet light from the sun.

Arctic ozone depletion is typically not as severe as that in the Antarctic. Over the South Pole, the sun barely or never sets around Christmas, creating a confluence of sunlight and cold in the atmosphere. Under these conditions, chlorine from CFCs eats away at ozone molecules.

Arctic ozone

Up north, however, the sun reappears in the sky in the spring as temperatures start to warm, so the conditions aren't as favorable for ozone depletion. But in 2011, the ozone concentration in the late winter Arctic was about 20 percent lower than average. [North vs. South Pole: 10 Wild Differences]

"You can safely say that 2011 was very atypical: In over 30 years of satellite records, we hadn't seen any time where it was this cold for this long," study researcher Susan Strahan, an atmospheric scientist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, said in a statement.

Using atmospheric simulations, Strahan and her colleagues found that a mix of cold temperatures, chlorine and an unusually strong Arctic vortex caused the odd thinning. The Arctic vortex is a region of fast-blowing circular winds that get stronger each fall, creating an eddy of chilled air around the pole.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 2011, the atmosphere was unusually quiet, allowing the Arctic vortex to remain strong well into the spring, after it usually breaks up. The reappearance of the sun in March while it was still especially cold created the conditions that led to the ozone thinning, the researchers report in the Journal of Geophysical Research - Atmospheres.

"Arctic ozone levels were possibly the lowest ever recorded, but they were still significantly higher than the Antarctic's," Strahan said. "There was about half as much ozone loss as in the Antarctic," and the levels remained above the threshold for calling the ozone loss an actual "hole," Strahan added.

Future outlook

Strahan and her team calculate that two-thirds of the thinning was caused by a combination of chlorine pollution and extreme cold. The remaining third was caused by the oddly quiet atmosphere, which prevented ozone molecules from elsewhere from moving in to fill the gap.

The ozone layer over the Arctic returned to normal in April 2011. It's unlikely that such thinning will become a reoccurring problem, because the meteorological conditions were so odd, Strahan said. Not only that, but CFC levels in the atmosphere are still declining.

"If 30 years from now we had the same meteorological conditions again, there would actually be less chlorine in the atmosphere, so the ozone depletion probably wouldn't be as severe," she said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas @sipappas. Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience, Facebook or Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus