Galileo's Optical Illusion Explained by Neuroscience

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

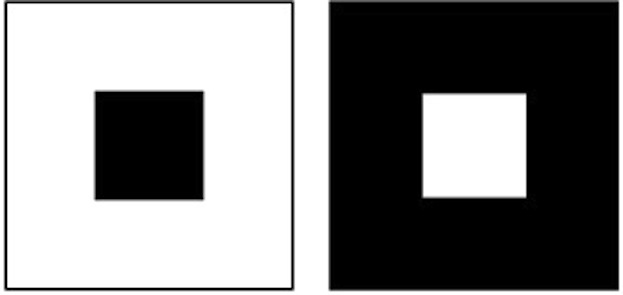

A light-colored object on a dark background appears larger than a dark object on a light background, but until recently, no one knew why.

Now, a study suggests that a difference in how the brain's cells respond to light and dark could explain the illusion. Neurons that respond to light objects may distort the objects more than neurons that respond to dark objects — possibly an advantage for human ancestors who needed to see in low-light conditions such as nighttime on the African savanna.

The distorted response to light might even hint at why reading in dim lighting may be bad for your eyes, the researchers said. [Eye Tricks: Gallery of Visual Illusions]

Article continues below"Every time we think about blur in an image, we usually think about optics," said Dr. Jose-Manuel Alonso, a neuroscientist at the State University of New York's College of Optometry and leader of the study detailed today (Feb. 10) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. "But what we're seeing is, there is another component — the neurons themselves," Alonso told Live Science.

Galileo's observation

When the Italian astronomer Galileo was making his observations of the planets, he noticed something strange. With the naked eye, the brighter of the two planets Venus appeared larger than Jupiter, but when viewed through a telescope, Jupiter was clearly larger.

Galileo believed the lens of the human eye caused this so-called "irradiation illusion." But the German physicist Hermann von Helmholtz showed that if the optics of the human eye were to blame, dark objects should be distorted just as much as light ones, which they were not.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the new study, Alonso and his colleagues used electrodes to record the electrical signals from neurons in the visual areas of anesthetized cats, monkeys and human brains while the researchers showed the animal and human participants dark shapes on a light background, light shapes on a dark background, or light or dark shapes on a gray background.

The visual system has two main channels: Neurons sensitive to light things are called "ON" neurons, whereas neurons sensitive to dark things are called "OFF" neurons. The researchers recorded from both types of neurons in the experiments.

The scientists found that the OFF neurons responded in a predictable, linear way to the dark shapes on light backgrounds, meaning the more contrast between a dark and light object the more active those neurons. But the ON neurons responded disproportionately to light shapes on dark backgrounds, meaning for the same amount of contrast they had a bigger response.

The distortion of light-sensitive neurons finally provides an answer to Galileo's puzzle. Venus, a light object on a dark background, appears disproportionately larger than Jupiter, a more distant, and thus darker, object.

Light in the night

The distorted vision turns out to very useful for humans, Alonso said, "because when you're in a very dark place, it allows you to see small amounts of light." This would be helpful to, say, alert you to predators at night. But during the day, more dark objects are visible, so it's better that these aren't distorted, Alonso said.

The study's results suggest the distortion may actually occur at the level of photoreceptors, the light-sensitive cells in the eye itself, rather than deeper in the brain. (This contrasts with Galileo's view that the lens of the eye was somehow to blame for the illusion.)

Having a stronger response to light than dark may be important when a baby's vision is developing. During the first few weeks after a baby is born, its vision is blurry, which could result in the light-dark distortion.

The findings could also open new windows into understanding problems with vision. Scientists believe that blur causes conditions such as myopia, or shortsightedness. "We now think 'neuronal blur' could be important part of this story," Alonso said.

Neuronal blur might even support the notion that reading in low light is bad for a person's eyes, though that subject remains for another study.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus