Fate of a Fertilized Egg: Why Some Embryos Don't Implant

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

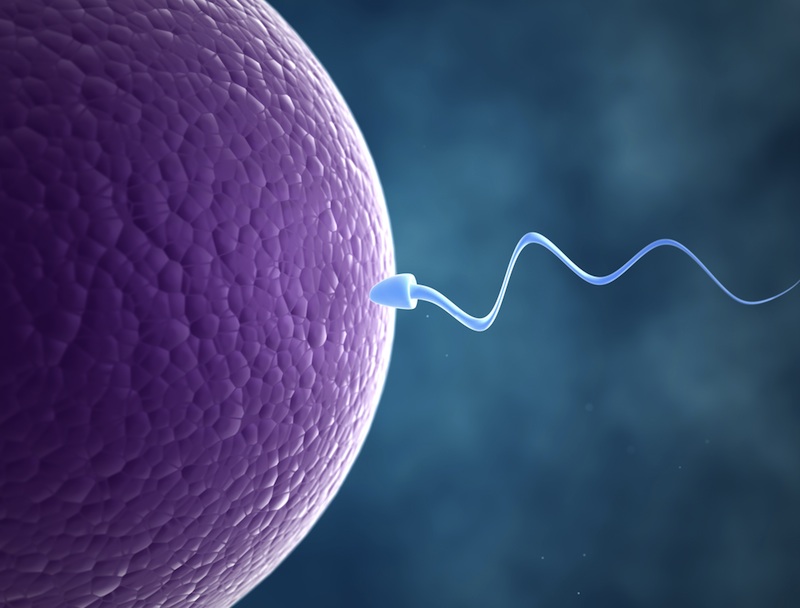

Some embryos fail to implant in the womb, while others implant successfully, leading to pregnancy, and a new study sheds light on why that's the case.

In the study, researchers found that human embryos typically produce a chemical called trypsin, which signals the womb to prepare its lining for implantation.

But in embryos with significant genetic abnormalities, this chemical signal was altered, and it produced a stress response in the womb that could make implantation unlikely, the researchers said. [9 Conditions That Pregnancy May Bring]

The researchers likened this process to an "entrance exam" set by the womb — an embryo needs to pass this test in order to implant.

But sometimes, the womb may make this exam too difficult or too easy, which could lead to the rejection of healthy embryos, or the implantation of embryos with development problems, the researchers said.

The new findings may have implications for fertility treatment, because one of the main reasons fertility treatments like in vitro fertilization (IVF) fail is that embryos don't implant.

With future research into the factors that govern implantation, it may be possible to identify women at risk for miscarriage or other pregnancy complications by taking a sample of her uterus lining, said Jan Brosens, a professor at the University of Warwick in the United Kingdom.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Certain drugs may also help the uterus set the stage for implantation, Brosens said.

"What we're looking at now is how to alter the lining of the womb so it can set this 'entrance exam' at the right level, and prevent implantation failure and miscarriages," Brosens said.

Human embryos are genetically diverse, and some have mutations that impair normal development. In some cases, these impaired embryos will not implant in the uterus, but often, they implant only to undergo miscarriage later.

In the study, the researchers used four-day-old human embryos that had been created by IVF. Some of the embryos were later implanted in women, and led to successful pregnancies, while others were not suitable for implantation because of developmental impairments. In both cases, the researchers took some of the liquid in which the embryos were growing, and transferred it to lab dishes containing cells of the uterus lining to conduct their experiments.

The study is published today (Feb. 6) in the journal Scientific Reports.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science@livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus