The Making of a Mysterious Renaissance Map

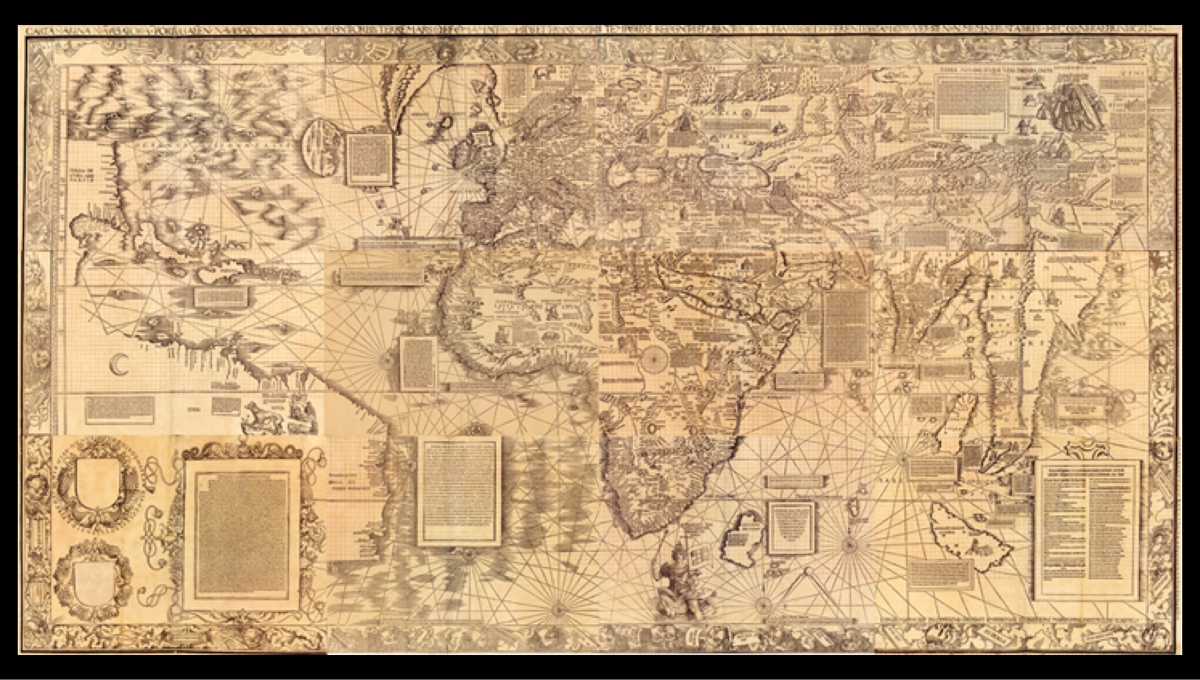

NEW YORK — Not much is known about how Renaissance cartographer Martin Waldseemüller created his 1516 "Carta marina" world map, possibly the most up-to-date conception of the world at the time.

But scholar Chet Van Duzer offered a rare peek into Waldseemüller's process Tuesday night (Oct. 22) during a talk here at the New York Public Library.

"A careful analysis of his sources allows us to go inside his workshop in Saint-Dié [in France] and essentially watch him at work as he made the Carta marina," Van Duzer, who is based at the Library of Congress, said in his talk. [See Photos of the Mysterious Carta Marina Map]

Van Duzer and his colleague John Hessler recently published a book on Waldseemüller's works entitled "Seeing the World Anew: The Radical Vision of Martin Waldseemüller's 1507 & 1516 World Maps," (Levenger Press, 2012).

Waldseemüller is best known for his 1507 world map, the first to call the New World "America." The cartographer began his career, Van Duzer said, by basing his maps on those of the Alexandrine geographer Claudius Ptolemy from the second century A.D. These maps were based on geographic descriptions in books, rather than direct maritime knowledge.

But in making the Carta marina, printed just nine years later, Waldseemüller abandoned his older sources in favor of contemporary nautical charts, maps of maritime regions and coastlines that seafaring explorers of the time would have used.

"When he came to create his new monumental world map, the Carta marina, Waldseemüller made a choice between these two competing cartographic systems, the Ptolemaic tradition and the nautical chart tradition," Van Duzer said — "and he based his map on nautical charts."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Waldseemüller based the Carta marina's coastlines on a nautical chart made by Nicolo de Caverio of Genoa in about 1503. The two maps have similar coastal place names and layouts. For example, the shapes of Greenland, the eastern coast of South America and Africa are nearly identical.

One major difference is that the Carta marina omits a large part of northeast Asia and Japan — probably because these regions were relatively unknown to European explorers, Van Duzer said.

Unlike the Caverio map, Waldseemüller's map is crowded with descriptive texts and illustrations of royal rulers.

The Carta marina depicts King Manuel of Portugal riding a sea monster near the southern tip of Africa, symbolizing Portugal's control of the sea route between Africa and India. The image was most likely inspired by an image of Neptune riding a sea monster in Italian printmaker Jacopo de’ Barbari’s print of Venice, Van Duzer said.

The map also includes an image of Noah's Ark resting in the mountains of Armenia, probably based on similar images in other nautical charts of the time, Van Duzer said.

The Carta marina depicts India as a land of animalistic people and barbarism. For instance, there's an image of "suttee," the Hindu practice of a widow burning herself to death on the funeral pyre of her husband. Other less well-known areas, such as America, contain images of cannibalism.

Despite these seemingly outdated images, the Carta marina still represents a leap forward in cartography, because Waldseemüller relied on much more updated sources than he did for his earlier 1507 map. In addition to nautical charts, Van Duzer's analysis reveals, the Renaissance cartographer relied on books written by recent explorers.

"The Carta marina is Waldseemüller’s most original creation," Van Duzer said. "He began his cartographic career by redrawing Ptolemy, but ended it by creating something entirely new, a mosaic image of the world with each stone of his own careful choosing."

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus