Just two decades after discovering the first world beyond our solar system, astronomers are closing in on alien planet No. 1,000.

Four of the five main databases that catalog the discoveries of exoplanets now list more than 900 confirmed alien worlds, and two of them peg the tally at 986 as of today (Sept. 26). So the 1,000th exoplanet may be announced in a matter of days or weeks, depending on which list you prefer.

That's a lot of progress since 1992, when researchers detected two planets orbiting a rotating neutron star, or pulsar, about 1,000 light-years from Earth. Confirmation of the first alien world circling a "normal" star like our sun did not come until 1995. [The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)]

And the discoveries will keep pouring in, as astronomers continue to hone their techniques and sift through the data returned by instruments on the ground and in space.

The biggest numbers in the near future should come from NASA's Kepler space telescope, which racked up many finds before being hobbled in May of this year when the second of its four orientation-maintaining reaction wheels failed.

Kepler has identified 3,588 planet candidates to date. Just 151 of these worlds have been confirmed so far, but mission scientists have said they expect at least 90 percent will end up being the real deal.

But even these numbers, as impressive as they are, represent just the tip of our Milky Way galaxy's immense planetary iceberg. Kepler studied a tiny patch of sky, after all, and it only spotted planets that happened to cross their stars' faces from the instrument's perspective.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Many more planets are thus out there, zipping undetected around their parent stars. Indeed, a team of researchers estimated last year that every Milky Way star hosts, on average, 1.6 worlds — meaning that our galaxy perhaps harbors 160 billion planets.

And those are just the worlds with obvious parent stars. In 2011, a different research team calculated that "rogue planets" (which cruise through space unbound to a star) may outnumber "normal" exoplanets by 50 percent or so.

Nailing down the numbers is of obvious interest, but what astronomers really want is a better understanding of the nature and diversity of alien worlds.

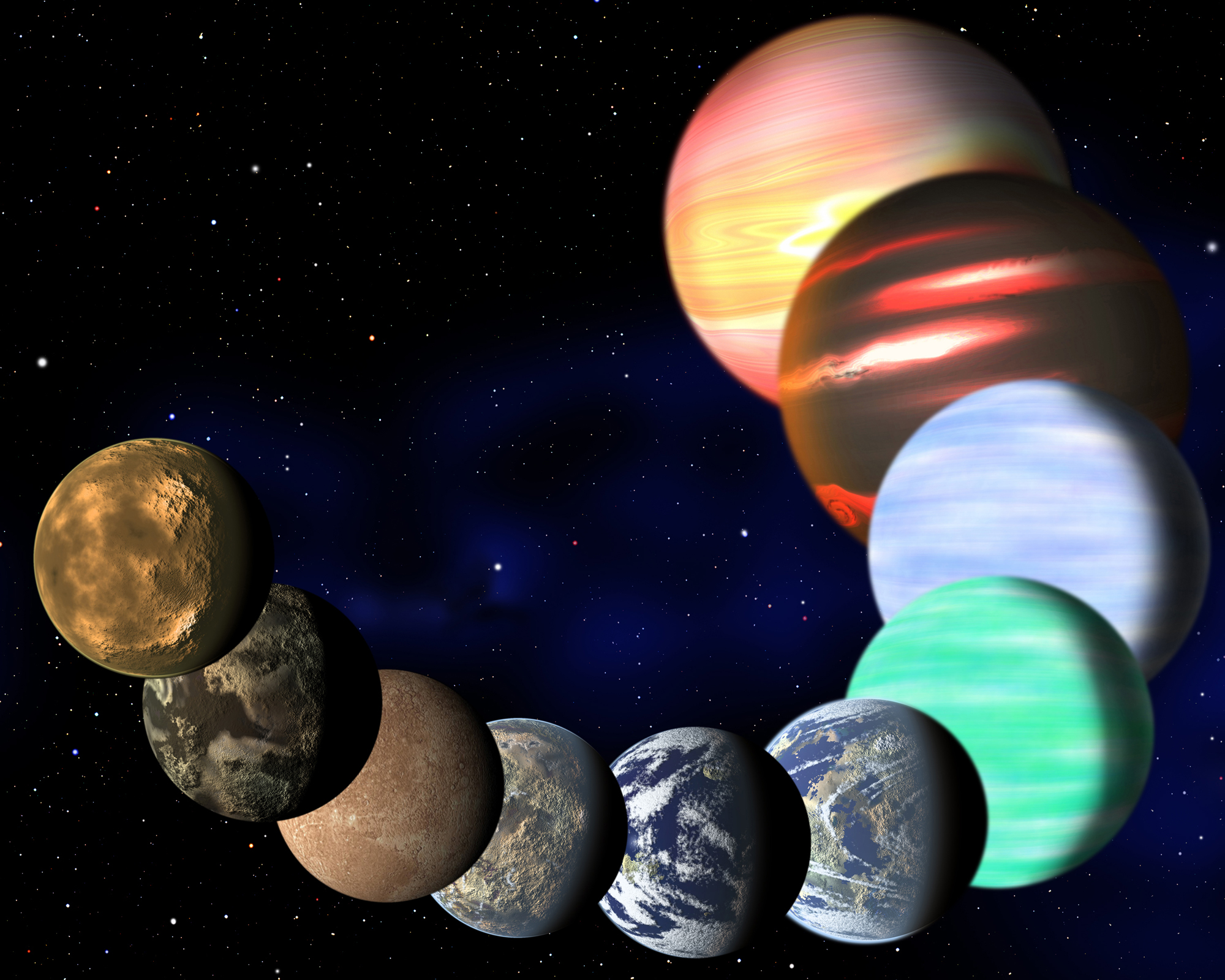

And it's becoming more and more apparent that this diversity is stunning. Scientists have found exoplanets as light and airy as Styrofoam, for example, and others as dense as iron. They've also discovered a number of worlds that appear to orbit in their stars' habitable zone — that just-right range of distances that could support the existence of liquid water and thus, perhaps, life as we know it.

But the search continues for possibly the biggest exoplanet prize: the first true alien Earth. Kepler was designed to determine how frequently Earth-like exoplanets occur throughout the Milky Way, and mission scientists have expressed confidence that they can still achieve that primay goal. So some Earth analogs likely lurk in Kepler's data, just waiting to be pulled out.

The five chief exoplanet-discovery databases, and their current tallies, are: the Extrasolar Planets Encyclopedia (986); the Exoplanets Catalog, run by the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo's Planetary Habitability Laboratory (986); the NASA Exoplanet Archive (905); the Exoplanet Orbit Database (732); and the Open Exoplanet Catalog (948).

The Planetary Habitability Lab keeps track of all five databases, whose different numbers highlight the uncertainties involved in exoplanet detection and confirmation.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.