Women Who Freeze Eggs Wish They Had Done It Sooner

Women who freeze their eggs in hopes of improving their fertility later in life feel positive about the experience, but wish they had done it at an earlier age, a new study finds.

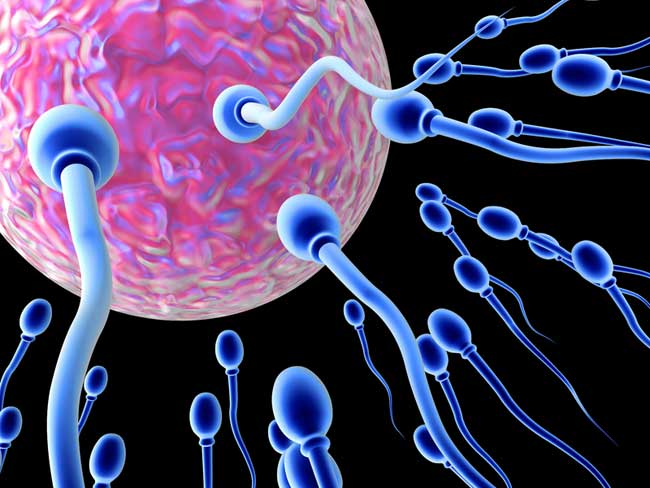

"Egg banking" — the practice of freezing eggs to circumvent age-related infertility — is becoming common in many countries, according to the researchers. Women may freeze their eggs for medical reasons, such as cancer treatment that may affect their fertility, but the new study involved women who underwent the procedure for social reasons, such as wanting to delay childbearing until they found the right partner, or until later in life.

While many women in the study said they did not expect they would ever have to actually use their frozen eggs, most also said they would do it again, according to the study, which was presented today (July 9) at the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology in Belgium. [5 Myths About Fertility Treatments]

However, Bonnie Steinbock, a professor of philosophy and bioethics at the University at Albany-SUNY, said the study's results are troubling.

Steinbock, who was not involved in the study, questioned how well-informed about egg banking the women in the study were, as well as the motives of the fertility clinics that perform egg freezing.

Egg banking does have risks, including a small risk of death. Furthermore, frozen eggs are not always successful in attempts to produce a pregnancy.

With regard to the women's positive response to egg donation, "When people have already done something, they rarely say they wouldn’t do it again," Steinbock told LiveScience.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study was a survey of 140 women in Belgium whose average age was 37. The women had considered egg banking between 2009 and 2011. The survey asked the women about their relationships, their attitudes toward egg banking and their future reproductive plans.

About 60 percent of the women surveyed wound up actually having their eggs harvested and frozen. Of the remaining women, some decided not to have the procedure, while for others, it wasn't successful.

More than a third of women who banked their eggs said they did not expect they would need to use them to have a child, the results showed. But still, more than 95 percent of these women said they would freeze their eggs again, with 70 percent saying they would do it at a younger age.

The women in the study who did bank their eggs were more willing to accept motherhood at a later age, compared with those who did not bank their eggs (43.8 years and 42.5 years, respectively. But women who banked their eggs were similar to those who didn't with regards to relationships, attempts to conceive and frequency of infertility.

The researchers said egg banking may provide psychological comfort to women, as shown by their positive feelings about the procedure. "Our results indicate that most women who have had [egg freezing] have no regrets about it, but do wish they had done so at a younger age," study researcher Dominic Stoop of the Free University of Brussels, Belgium's Centre for Reproductive Medicine said in a statement.

But Steinbock said, "We don’t want women spending a ton of money on procedures that may or may not be necessary." She estimated the cost of one cycle of egg freezing could be about $10,000, and the procedure is not always covered by insurance.

While it's true that fertility declines with age, women in their 20s still have years of fertility ahead of them, so freezing their eggs then may be unnecessary, Steinbock said. By contrast, she said, "women should not delay childbearing on grounds that they've got frozen eggs."

If society made it easier for parents of both sexes to take time off work, women might not need to put off childbearing, Steinbock said.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com .