Gallery: The Haunting Splendor of Chile's Atacama Desert

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Atacama

The driest place in the world, Chile's Atacama Desert, certainly feels it. The air is so dry lips chap and skin cracks easily. But the climate is soothing too, with almost no humidity and occasional refreshing breezes.

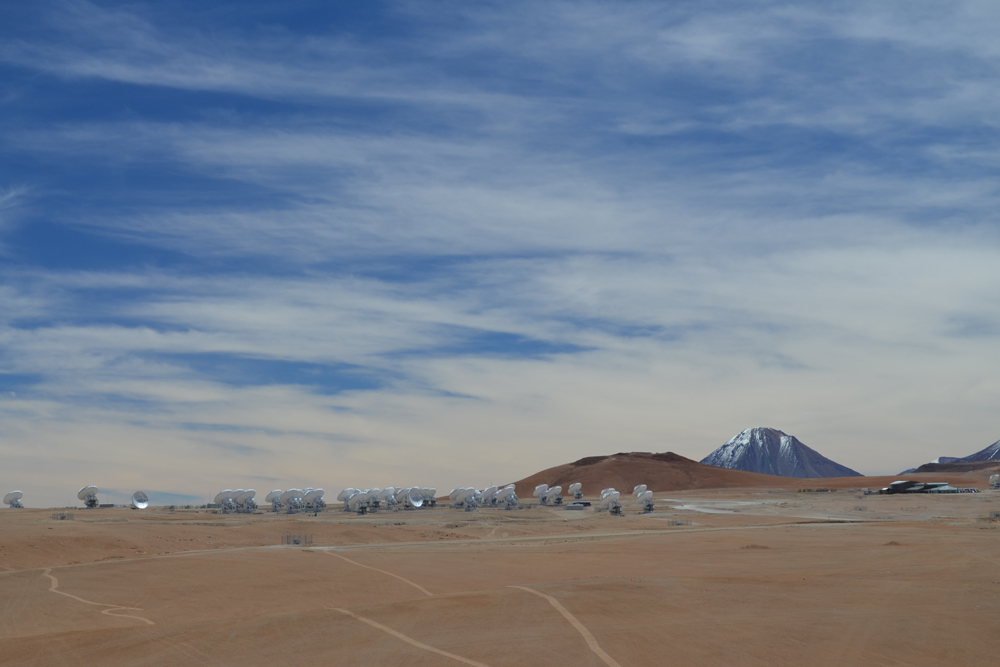

In March 2013 I was lucky enough to travel to the Atacama for the inauguration of the ALMA telescope (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) a new collection of 66 astronomical radio dishes on a trip sponsored by the U.S. National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

In addition to the cosmic splendor of the observatory, I relished the desert experience, and soaked up as much as I could of the otherworldly atmosphere of the Atacama. My desert journey began in the northern Chilean mining town of Calama, where I flew in from the capital Santiago.

Wrinkly Hills

Driving from Calama to the small oasis town of San Pedro de Atacama, the landscape is instantly stunning. Wrinkled hills of sand quickly dominate the terrain, stretching out as far as the eye can see.

The Atacama Desert is a 600-mile-long (1,000 kilometers) plateau in the north of Chile, near the borders of Peru, Bolivia and Argentina. The harsh land is sparsely populated, with few signs of humanity between the airport and the outpost of San Pedro.

Salt

The desert is littered with salt flats, and salt can be seen as a thin layer of white coating much of the red rock of the Atacama. The salt originated in volcanic eruptions from the nearby Andes, stirred up by the collision of the Nazca Plate in the eastern Pacific Ocean with the South American Plate on the continent.

The Andes

The Atacama Desert is bordered by the Andes Mountains on the east, and their snow-capped peaks can be seen from almost everywhere in the Atacama. Extending about 4,300 miles (7,000 km) from north to south, the Andes are the longest continental mountain range in the world. They define the entire eastern boundary of Chile and extend past it northward through Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Columbia and Venezuela.

San Pedro de Atacama

The tiny town of San Pedro de Atacama arose around a rare oasis in the desert. Now it is the taking-off point for many tourists visiting the wonders of the Atacama, as well as astronomers passing through on their way to ALMA and other famous telescopes nearby. The town is home to about 5,000 people, including some who can trace their lineage back to the region's first inhabitants, the Atacameños.

The town is dusty and dry with a liveliness that comes as a surprise after the miles and miles of serene desert all around it. In addition to an archaeological museum and a historic church, San Pedro has sprung up with shops, restaurants and hotels catering to the sizable number of tourists who pass through.

Rare vegetation

The terrain of the Atacama varies quite a bit, and while some regions are cracked and dry as bone, others do have some green vegetation, especially near San Pedro de Atacama. This vegetation can also vary, from scrub brush to green tufts of grass to prickly cacti. Still, living things of all kinds are rare in this harsh environment.

While some spots in the desert do occasionally get rain, other areas have gone hundreds of years without precipitation, and some river beds show evidence of being dry for 120,000 years. The area of San Pedro de Atacama gets an average of about 1.4 inches (35 mm) of rainfall a year.

ALMA Operations Center

The Operations Support Facility for the ALMA telescope lies high above the desert. The telescope itself is at an altitude of about 16,500 feet (5,000 meters) on the Chajnantor Plateau, but the main control center for the scientists and technicians running it is lower down the hill. When scientists do venture up to the high site, they often breathe supplemental oxygen to compensate for the thin atmosphere available there.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Volcano Views

The Atacama is near a large concentration of white-capped volcanoes, many of them active, in the Altiplano-Puna volcanic plateau. Volcanoes are striking in person, looking like perfect triangles with their top corners lopped off. Ominous smoke can even be seen leaking from the top of some Chilean volcanoes, casting a pall over the desert below them.

Atacama Cactus

A lone cactus stands on a ridge dotted with low green scrub on the road winding up toward the ALMA telescope's Chajnantor Plateau site.

The sky in the desert can be strikingly blue, and the night skies are stunningly clear. The ALMA site was chosen because of the high, dry climate, where clouds are rare and image-blurring moisture is at a minimum.

Martian Landscape

Some parts of the Atacama are so red and dry they seem more like Mars than Earth. This resemblance has not gone unnoticed by NASA, in fact, and the agency has even used the area to test some technologies intended for robotic Mars explorers. Film crews have also shot scenes set on Mars in this desert.

High & Dry

The 66 radio antennas in the ALMA array stand out as man-made objects against the stark natural backdrop of the desert scene. Here, 16,500 feet (5,000 meters) up on the Chajnantor Plateau, the telescope escapes much of the moisture of Earth's atmosphere, which blurs light coming in from above.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus