Chile Quake & Tsunami Dramatically Altered Ecosystems

The earthquake and tsunami that rocked Chile in 2010 unleashed substantial and surprising changes on ecosystems there, yielding insights on how these natural disasters can affect life and how sea level rise might affect the world, researchers say.

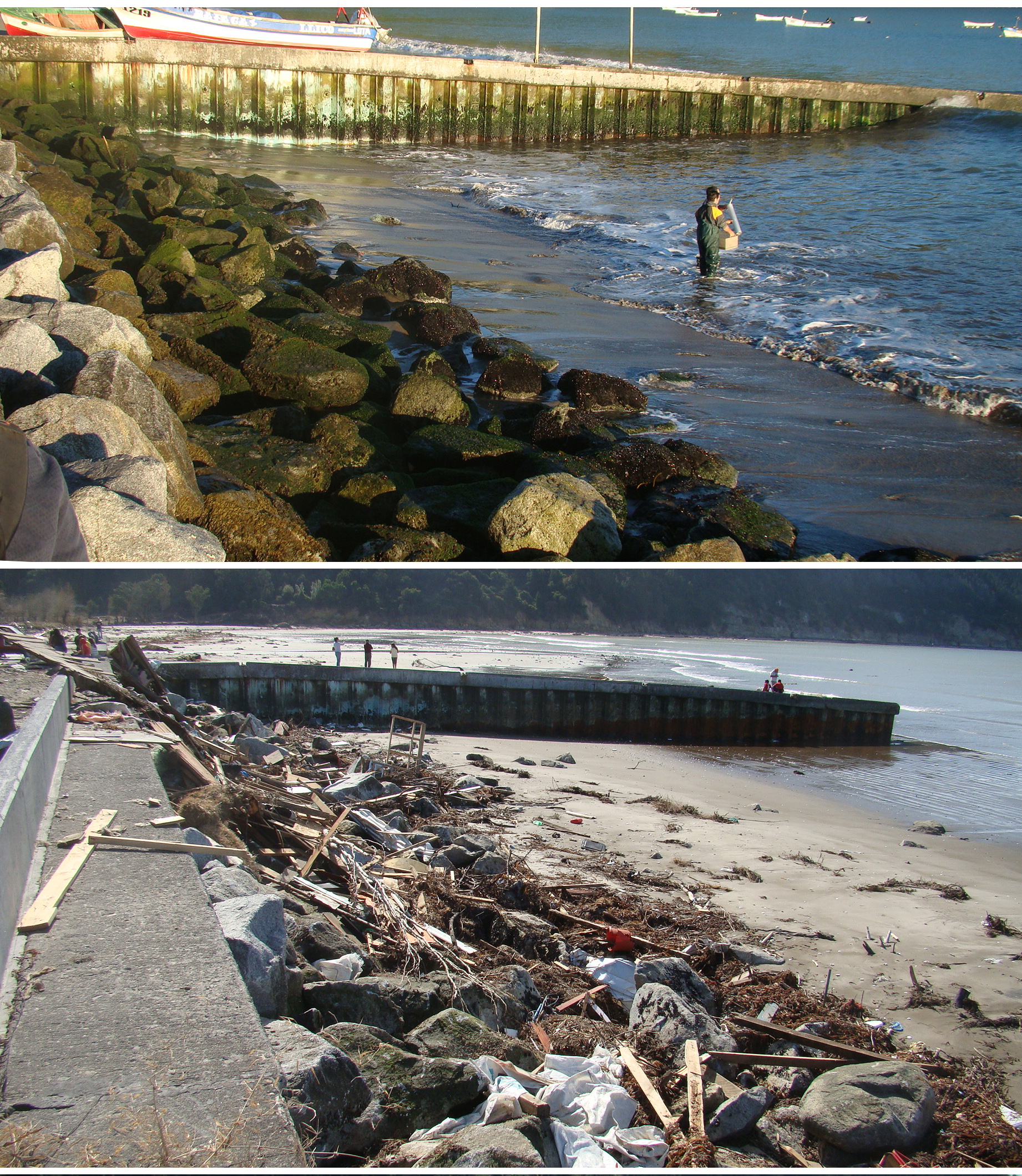

The magnitude 8.8 earthquake that hit Chile struck off an area of the coast where 80 percent of the population lives. The massive quake triggered a tsunami reaching about 30 feet (10 meters) high that wreaked havoc on coastal communities: It killed more than 500 people, injured about 12,000 more, and damaged or destroyed at least 370,000 houses.

It makes sense that such earthshaking catastrophes would have drastic consequences on ecosystems in the affected areas. However, if researchers lack enough data about the environment before a disaster strikes, as is usually the case, it can be difficult to decipher these effects. With the 2010 Chile quake, scientists were able to conduct an unprecedented report of its ecological implications based on data collected on coastal ecosystems shortly before and up to 10 months after the event.

The sandy beaches of Chile apparently experienced significant and lasting changes because of the earthquake and tsunami. The responses of ecosystems there depended strongly on the amount of land level change, how mobile life there was, the type of shoreline, and the degree of human alteration of the coast. For instance, in places where the beaches sank and did not have manmade sea walls and other artificial "coastal armoring" to keep water out, intertidal animal populations — ones living in the part of the seashore that is covered at high tide and uncovered at low tide — all dropped, presumably because their habitats were submerged.

The most unexpected results came from uplifted sandy beaches. Previously, intertidal species had been kept from these beaches due to coastal armoring. After the earthquake, these species rapidly colonized the new stretch of beach the quake raised up in front of the sea walls.

"This is the first time this has been seen before,"said researcher Eduardo Jaramillo, a coastal ecologist at the Southern University of Chile.

"Plants are coming back in places where there haven't been plants, as far as we know, for a very long time," said researcher Jenny Dugan, a biologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara. "This is not the initial ecological response you might expect from a major earthquake and tsunami."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These findings could help inform future human alterations to coastlines. For instance, as sea levels rise globally, it might be wise to consider how beach habitats in front of sea walls might get changed.

"Around the Pacific coast, there may be another earthquake tomorrow, the day past tomorrow, we don't know," Jaramillo told OurAmazingPlanet. "With this kind of research, hopefully we can learn something from them." [7 Ways Earth Changes in Blink of an Eye]

The scientists detailed their findings online May 2 in the journal PLoS ONE.

Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.