Ancient Warming Spelled Boon, Not Doom, for Tropical Forests

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Evidence unearthed from ancient pollen may offer the Amazon and other tropical rainforests new hope in the face of climate change. According to a new study, a period of rapid warming nearly 60 million years ago actually boosted tropical plant diversity.

"We found that the tropical forests generally didn't suffer any damage from the warming," said study co-author Diana Ochoa of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, in central Panama. "We weren't expecting that."

However, the researchers caution that differences in today's conditions, including far fewer "pristine" forests and substantially speedier warming, limit the optimism that can be extrapolated from the natural record.

Ancient warming

The Late Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) occurred about 56 million years ago and may have lasted 200,000 years. During this time, a massive release of carbon dioxide increased atmospheric levels of that greenhouse gas to about 2.5 times what they are today, which translated into an abrupt warming of about 8 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees Celsius) over the PETM's first 10,000 years.

While various climate records from around the world date back to this period, including evidence that North American plants responded to the temperature rise by migrating northward, the ancient fate of tropical ecosystems remained a mystery. Some scientists simply made assumptions based on experiments conducted in chambers with high carbon dioxide concentrations: The plants usually died, or were at least damaged.

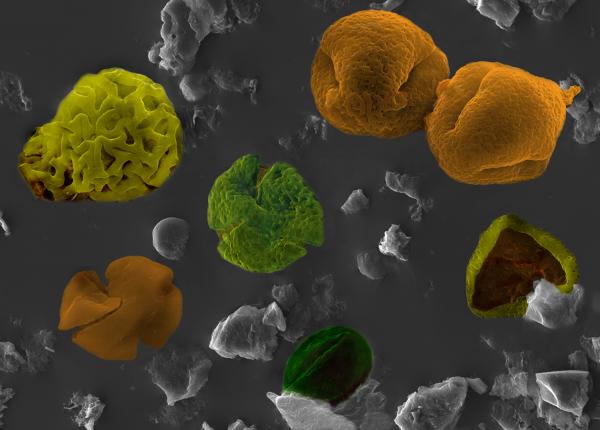

But when Ochoa and her colleagues split open old rocks from three regions of Colombia and Venezuela and analyzed the pollen preserved inside, they saw another story.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Different plants, such as oak and hickory, have very specific pollen morphologies, so we can compare families of plants," she explained. "Just by looking at the pollen, we found a marked increase in diversity. There were an important number of species added to the pre-existing vegetation." Most of the additions were flowering plants.

The researchers aren't certain just how the warming may have triggered the boon in diversity. All they know for sure is that the pattern appeared consistent in all three regions they analyzed.

"This change in diversity is not limited to plants," added Ochoa. "Somehow this warming triggered great diversity in many groups."

Comparisons to today

Still, the team emphasizes that while the PETM may be the closest historic scenario to compare with current warming, the ancient event differed substantially.

For one, it was a natural process. "No human activity was influencing the event," noted Ochoa. Deforestation , hunting and other human activities continue to weaken today's forests, potentially hampering their resilience to the current warming trend.

Further, although rapid in the context of the planet's 4.5-billion-year history, the 10,000 years it took Earth to warm up at the beginning of the PETM is about 10 times slower than the speed with which Earth is heating up today. Average global temperatures have climbed about 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit (0.8 degrees C) over the last century. Tropical temperatures are expected to increase by an additional 5.4 degrees F (3 C) by the end of this century.

During the PETM, species may have had enough time to genetically adjust themselves to the system, Ochoa posited.

"Plants may be genetically adapted to survive under hot conditions, at least when human activity is not applied," she said. "But we are heating things up so fast today that we may not be allowing them enough time and space to adjust even if they know how, and have the genetic pool to do it."

The study is detailed in the Nov. 12 edition of the journal Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus