As Desert Dust Blows, Climate Researchers Will Track It

Most people spend their lives trying to avoid dust or get rid of it, but researchers from the University of Alabama in Huntsville are planning to spend the next three years pursuing 770 million tons of dust carried from the Sahara into the atmosphere annually and trying to determine its impact on our climate.

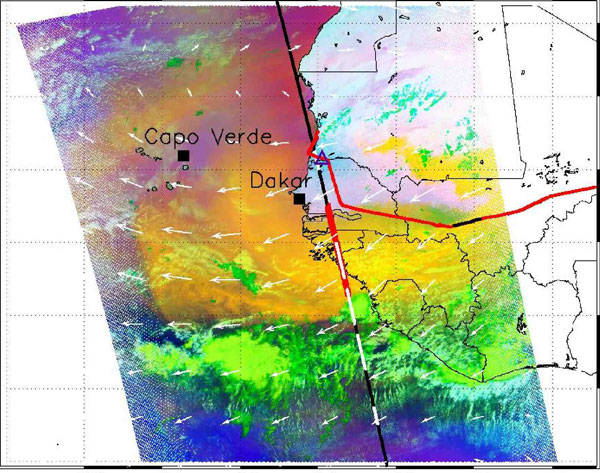

Some of the dust from the world's largest desert falls back to earth before it leaves North Africa. Some of it blows out over the Atlantic Ocean, carried by wind to South America and the United States, or over the Mediterranean Sea.

Wherever the dust goes, these scientists will be using data from several research satellites to assess its effect on the planet.

"The people who build climate models make some assumptions about dust and its impact on the climate," said Sundar Christopher, an Alabama in Huntsville professor of atmospheric science. "We want to learn more about the characteristics of this dust, its concentrations in the atmosphere and its impact on the global energy budget so we can replace those assumptions with real data."

A dust particle measures about 10 microns across, or about one-tenth the width of a human hair. Their particular size gives particles the ability to absorb some solar radiation. That radiation heats up the particle, which then radiates the heat into the air.

Dust particles can also cool the atmosphere by reflecting some incoming solar radiation back into space. To add further to its effects, dust absorbs thermal energy rising from the ground and re-radiates it either toward space or back toward Earth's surface.

"One thing we want to do is calculate how reflective dust is, because not all dust is created equal," Christopher said. "We're trying to calculate reflectivity so we can say with precision how much sunlight is being reflected."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dust from the Sahara was chosen because that vast desert it covers about 3.5 million square miles (9.1 million square kilometers) contributes about half of the dust carried into the atmosphere every year, and Christopher said the dust is more "pristine" than dust from U.S. or Asian deserts, which often contains pollutants.

The composition and shape of dust particles are complex, and the composition varies depending on which part of the Sahara it comes from. Some absorbs more solar energy than others.

Studying the Saharan dust is also a challenge because the dust in the atmosphere looks very much like the surface below it. Only in the past few years have new instruments and techniques been developed that help scientists detect which is dust and which is desert.

Christopher has received a grant of almost $500,000 through NASA's Calipso program ("Cloud-Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation") to support the research for the next three years.

- The World's Weirdest Weather

- Infographic: Earth's Atmosphere Top to Bottom

- 101 Amazing Earth Facts

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus