Conservation's Biggest Challenge? The Legacy of Colonialism (Op-Ed)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Species appear and disappear in the blink of a geologic eye; that's a rule of life. There have been five mass extinctions in Earth's past, when changes to the climate, the emergence of new adaptations and even cosmic interventions caused many unique life-forms to die off. A sixth mass extinction is currently underway, and the only thing that distinguishes it from its predecessors is the cause: humans.

Why are so many of Earth's species going extinct? The reasons are myriad and include loss of habitat, overhunting and competition with non-native species that were introduced by people. But how did we get to this point, so soon after an era in which the world's bounty seemed endless, with flocks of passenger pigeons so large that they covered the sun and herds of bison that numbered in the thousands?

Some would explain that these sudden declines in the past century stem from modern overconsumption. But we must look back even further, to the period of European colonization that began in the 1500s and ended 400 years later. [10 Species You Can Kiss Goodbye]

Article continues belowIn fact, many of the European nations that are even now forcing conservation measures on countries across the world are to blame for the current conservation crisis.

Tigers, for example, are the darlings of conservation efforts worldwide. An estimated 80,000 tigers were slaughtered in India between 1875 and 1925, when the country was under British rule; currently, the global tiger population is less than 4,000 individuals, according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

American bison, on the other hand, represent a modern conservation success story — or so it would seem. Federal protections saved bison from extinction in the mid-1900s, but the iconic animals were brought to the brink of extinction by European colonizers. Driven largely by a desire to destroy a much-needed indigenous resource, colonizers' widespread slaughter reduced bison populations from over 30 million animals to fewer than 100 individuals in less than a century, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reported.

Indigenous traditions

Conserving and managing natural resources isn't a modern concept; indigenous peoples across the world have practiced it for generations. They might not have had the statistical models and the technology available today, but they had experience-based knowledge, traditions, rituals.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In pre-colonial Zimbabwe, it was taboo to cut the muhacha tree, also known as the Mobola plum tree, as it was nutritionally and culturally important. It was also forbidden to kill certain rare animals like the pangolin without permission from the local chief, researchers reported in 2018, in the journal Scientifica. In Guatemala, the mythical status of the resplendent quetzal, a brilliantly colored bird, helped promote its conservation, according to a study published in 2003 in the journal Ecology and Society.

Totemic relationships limited or outright banned the hunting of certain species such as elephants among ethnic groups like the Ikoma in Tanzania, while Inuits saw themselves not as land owners, but as land inhabitants, playing a part in a larger cycle that helped to sustain them.

It was through these mores that indigenous peoples conserved and sustainably used their natural resources.

In most cases, the poachers and small-time loggers in the news stories are local individuals: a Congolese man with a rusted axe in the forest, or a Vietnamese boy setting snares, for example. However, a look back in history reveals that the people who have historically dealt the most devastating damage to forests and wildlife worldwide were European colonizers.

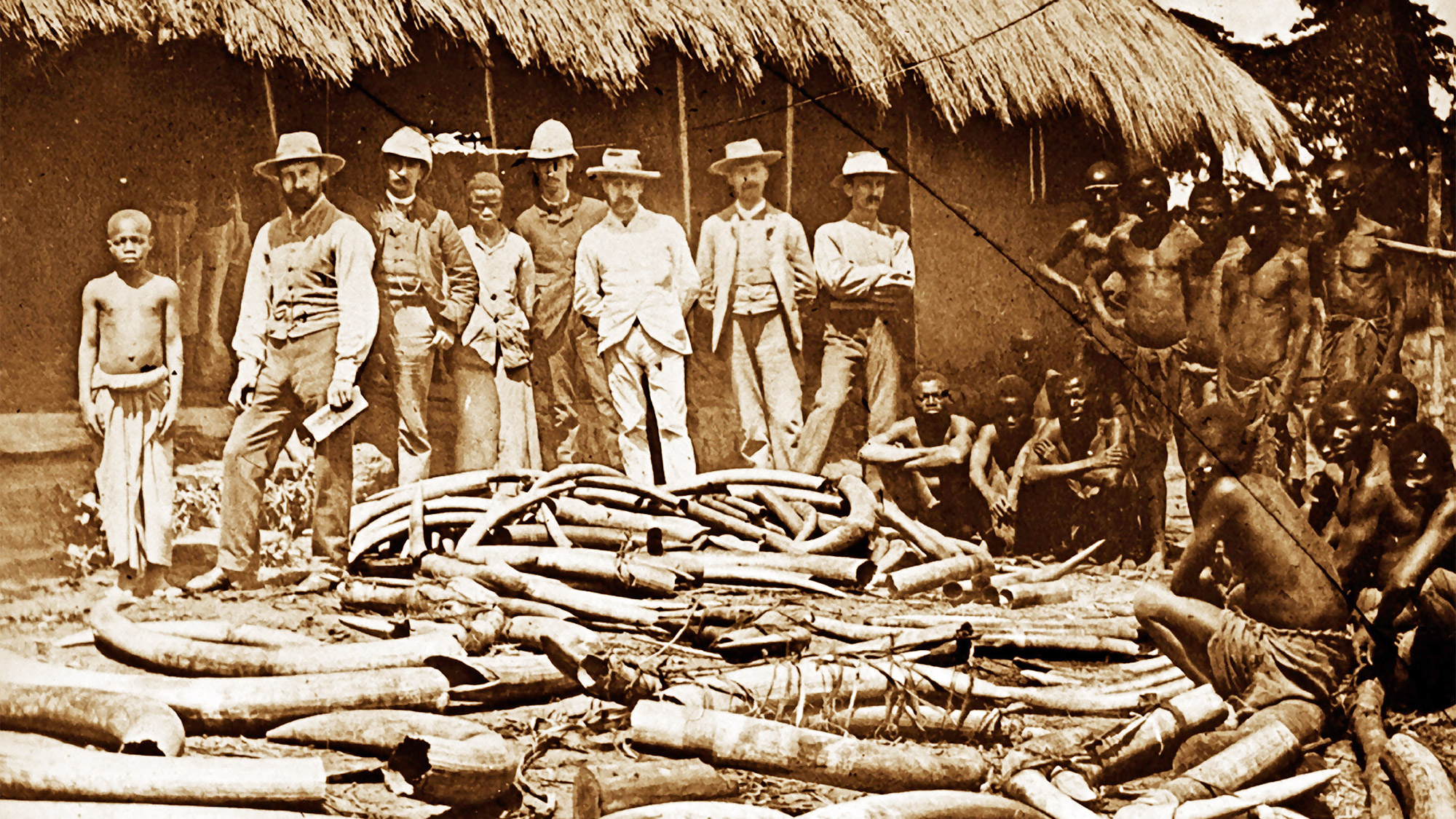

European colonization brought not only a clash of cultures, but also an almost total decimation of those traditions that kept order within indigenous societies and helped to conserve natural resources, according to the Scientifica study . Europeans saw that Africa, the Americas and Asia were rich in fur and feather, skin and wood, gold and ivory; using a mixture of religious supremacy and scientific racism, colonizers gave themselves permission to carve up those continents like so much meat, descending upon exotic so-called Edens like locusts.

Forests were cut down. Precious metals were dug up. Wild animals were killed. All of this natural wealth was stolen from indigenous peoples and used to enrich what is now called the "developed" world. [Photos: Wild Animals of the Serengeti]

Too little, too late

Decades after white colonialists ravaged the world’s natural resources, concerns arose — locally and globally — about conserving what little of those precious resources remained. And indigenous people, as they had before, paid the price then, and are still paying today. From Virunga to Rajasthan, Yellowstone to Kruger, indigenous people were barred from areas declared protected by someone hundreds of miles away, and were forced to relocate from lands they had occupied for generations.

Horrific acts are committed in the name of conservation: kidnapping suspected poachers in the dead of night, beatings for imagined infractions, sexual assaults and even murder. In 2017, Newsweek reported that an estimated 500 men were shot in 2016 while in or near Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique, on suspicion of poaching. National Geographic also reported accounts of suspected poachers who were tortured or raped by military officers in Tanzania.

Today, on social media, millions across the world sit in judgment on reports of poaching, ready to favorite, retweet, share or call for blood in the comments, and throw money at a problem they're sure they understand based on one-sided conservation narratives.

As in most stories, conservation has heroes and villains. The villains — poachers — are indigenous people across the world who have historically been defrauded, violated, murdered and displaced. Though they may no longer be under colonial rule, they are still criminalized in the name of conservation, even when their own survival is at stake.

Meanwhile, so-called conservation heroes act as gatekeepers to resources that were never theirs to begin with, regulating what little remains from the people who have already lost the most.

In past centuries, colonialism perpetrated great crimes that affected millions; the lasting impact of that legacy is carried by those still living and will be shouldered by those who have yet to be born. According to a United Nations report published online May 9, thousands and thousands of species are currently faced with extinction, and humanity’s ability to live in the only home we have (and most likely ever will know) is swiftly eroding.

The nations that built empires across the world — and in doing so, fueled today's conservation emergencies — will be cushioned against the worst of the fallout as ecosystems collapse worldwide. And yet, the most ethical action would be to voluntarily relinquish the wealth and resources that protect them, extending that protection to everyone. We who benefit from colonialism’s violent past must acknowledge our role in causing the crises that face humanity, and seek to recompense those who have been wronged.

- 10 Easy Ways to Help Wildlife, Every Day (Photos)

- Species Success Stories: 10 Animals Back from the Brink

- Wipe Out: History's Most Mysterious Extinctions

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus