What Ever Happened to the Richter Scale?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The Richter scale is perhaps the most famous of earthquake magnitude scales. But it was only intended for limited use, according to the United States Geological Service (USGS).

Created by Charles Richter in 1935, the scale was meant to assess the relative size of an an earthquake in quake-prone California and was created specifically for that area only, the USGS' Lisa Wald told Live Science.

While other magnitude scales are available, there is one that the science community prefers today, said Wald. She is a geophysicist and science communicator for the USGS Earthquake Hazards Program who has written before about the science of earthquakes.

"There is one magnitude scale that tends to work most of the time, and become kind of the standard that most people use now, and it's moment magnitude," Wald said.

The Richter scale only was accurate in California for those earthquakes that hit within about 370 miles (600 kilometers) of seismometers. These days, however, scientists detect temblors on the other side of the Earth.

Another issue with Richter was that the scale was calculated from one type of earthquake wave, a kind that doesn't help much when measuring truly massive quakes, like Japan's magnitude-9 in 2011.

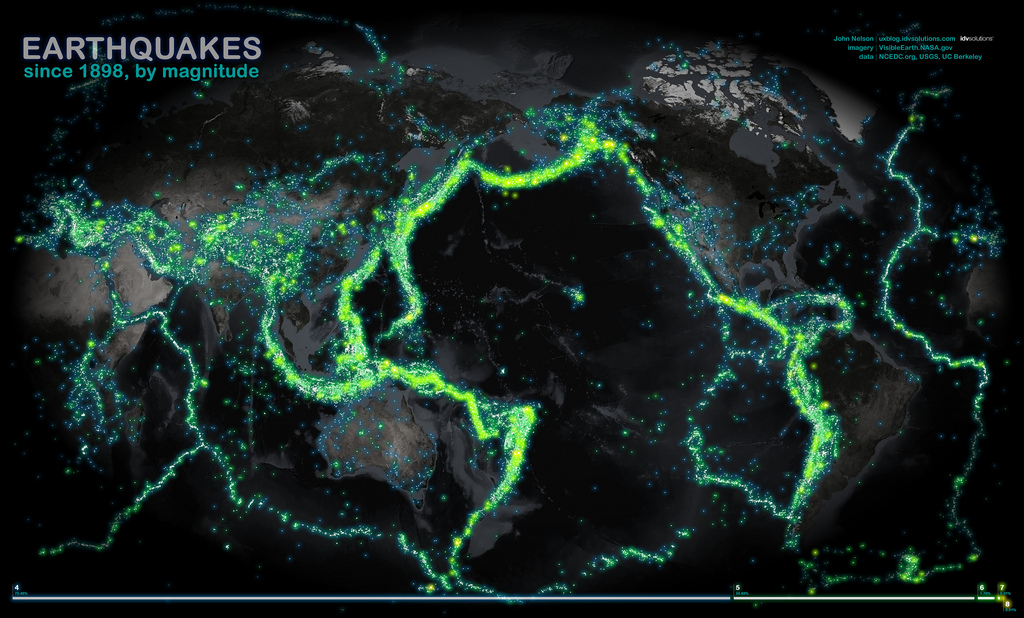

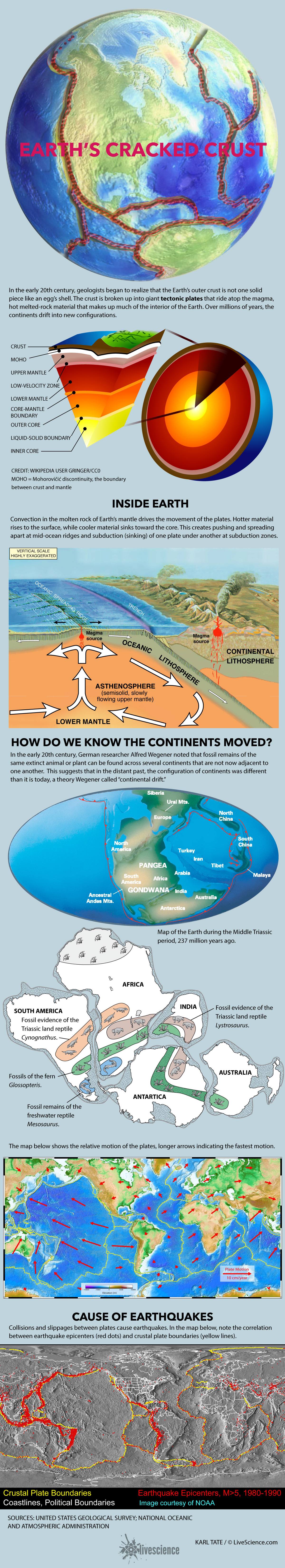

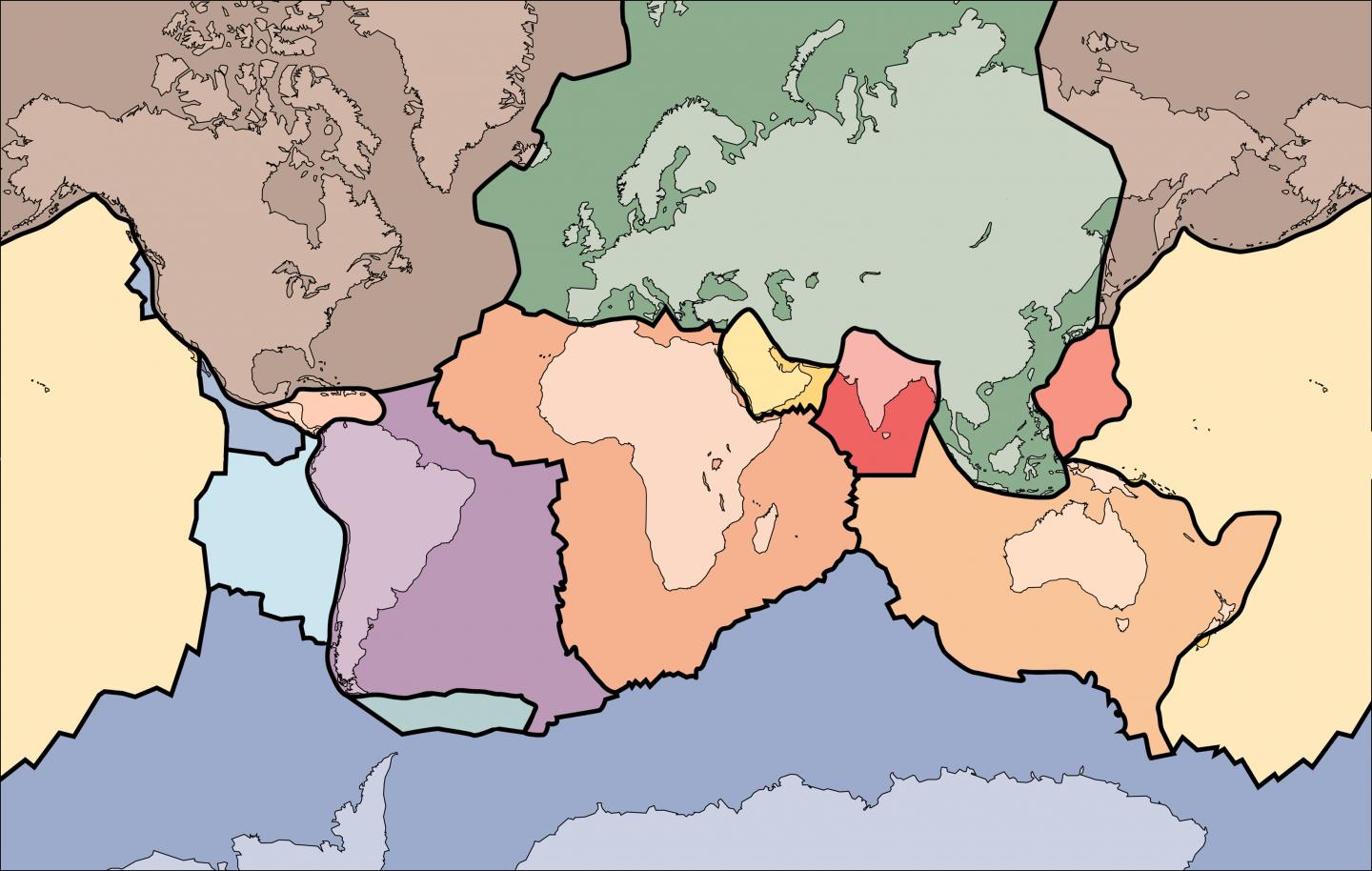

The moment magnitude scale, by contrast, captures all the different seismic waves from an earthquake, giving a better idea of the shaking and possible damage. Earthquakes arise from movements of tectonic plates deep underneath the surface, and Wald said moment magnitude can show the size of the fault, the amount of fault slippage and friction, among other factors.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Wald added there are numerous scales available that assess different types of earthquake waves. The main ones used by scientists are S-waves (surface waves) and P-waves (pressure waves.)

For example, as some very large earthquakes have large surface waves, seismologists might use surface wave magnitude to assess the energy produced. It's also common for seismologists to compare moment magnitude with these more localized scales to see how they agree or disagree, Wald said.

"I have to tell you that magnitude is one of the most difficult concepts to understand," added Wald. Magnitude describes the size of the earthquake at the source in terms of the energy that was released.

Shaking, by contrast, is "more diagnostic for the impact of the earthquake on structures, utilities, things under the ground," she said. Naturally, shaking is greatest at the source of the earthquake and diminishes by distance, although other variables like soil type can influence this metric.

Earthquakes are measured by numerous networks around the world. The United States' Advanced National Seismic System includes a backbone of USGS-managed stations and numerous regional networks that contribute data to the system as well, Wald said.

Particularly dense networks like the Southern California Seismic Network, managed by the California Institute of Technology, are very helpful in assessing smaller earthquakes due to the number of stations available, she added.

On a larger scale, there is also the Global Seismographic Network that is operated by the USGS, which can record moderate- to large-sized earthquakes anywhere in the world.

Wald cautioned that the science of earthquakes more generally is quite young, with only about 100 years of data compared to very old disciplines like medicine and biology. As such, the data tends to change rapidly as the community's experience accumulates.

"Our capabilities are getting better all the time, so we can include more details as techniques are being discovered, and all of those things that are improved may change the answer," Wald said.

While usually the answer only "incrementally" changes, Wald said the public needs to realize that earthquake data may be very different in five- or 10-year increments.

"We weren't necessarily wrong, but it was just the best answer we could come up with [at the time] with the available data and tools that we had."

Originally published on Live Science.

- Elizabeth HowellLive Science Contributor

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus