Tomorrow's Diapers May Be Made from Greenhouse Gas

A chemical found in diapers and other materials could be made more cheaply and sustainably from carbon dioxide, research shows.

Each year, companies produce billions of tons of the chemical known as acrylate, which is used to make the superabsorbent material that lines polyester fabrics and diapers. The polymer it forms is one of the components in diapers, along with the polyethylene in their outer layer, that makes them resist degradation in landfills. Companies usually make acrylate by heating propylene, a chemical found in crude oil. Now, researchers have developed a way to produce the chemical using carbon dioxide and a strong acid.

"What we're interested in is enhancing both the economics and the sustainability of how acrylate is made," chemist Wesley Bernskoetter of Brown University, who led the study, said in a statement. The research was published in the journal Organometallics. "Right now, everything that goes into making it is from relatively expensive, nonrenewable carbon sources."

Scientists have been working on alternative ways to produce the diaper chemical since the 1980s, for instance by mixing carbon dioxide gas with ethylene gas using a metal catalyst like nickel. The planet certainly has no shortage of carbon dioxide, and ethylene can be made from plant biomass (and is cheaper than propylene).

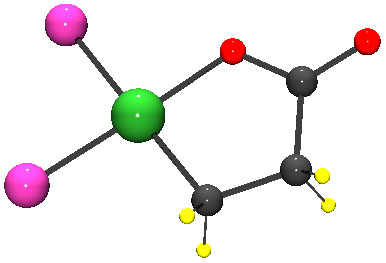

Ethylene and carbon dioxide undergo a chemical reaction to form a molecule with a five-atom ring of oxygen, nickel and three carbon atoms. To form acrylate, this ring must be broken so that a double bond can form between two of the carbon atoms, a process known as elimination.

Breaking open that ring has proven challenging. But Bernskoetter and colleagues found that chemicals known as Lewis acids can crack this ring open by stealing electrons away from the bond between nickel and oxygen. Using this method, the researchers were able to quickly slice open the ring to produce acrylate.

The process could ultimately be scaled up to produce acrylate in an industrial setting, Bernskoetter said. The next step will be adjusting the strength of the Lewis acid. As a proof of concept, the researchers used the strongest acid possible, one made from boron. This acid cannot be used in a repeatable process, however, because it bonds to the acrylate.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Bernskoetter is optimistic about finding an acid that will work, because Lewis acids come in a wide array of strengths.

The payoff for developing a successful new method of creating acrylate could be big, Bernskoetter said. "It's around a $2 billion-a-year industry," he said. "If we can find a way to make acrylate more cheaply, we think the industry will be interested."

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus