Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

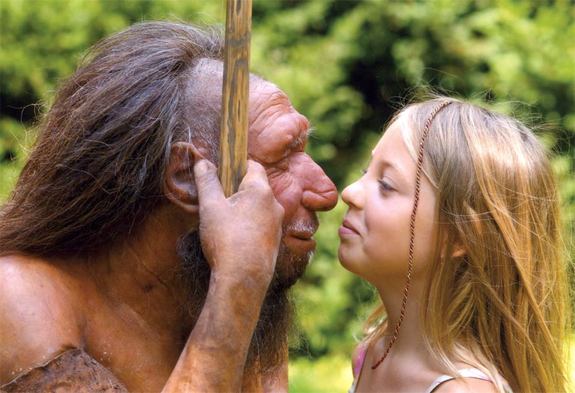

Neanderthals' keen vision may explain why they couldn't cope with environmental change and died out, despite having the same sized brains as modern humans, new research suggests.

The findings, published today (March 12) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, suggest that Neanderthals developed massive visual regions in their brains to compensate for Europe's low light levels. That, however, reduced the brain space available for social cognition.

"We have a social brain, whereas Neanderthals appear to have a visual brain," said Clive Gamble, an archaeologist at the University of Southampton, who was not involved in the study.

As a result, the extinct hominids had smaller social and trading networks to rely on when conditions got tough. That may have caused Neanderthals to die off around 35,000 years ago.

Brain size riddle

Just how smart Neanderthals were has been a long-standing debate.

"Either they get regarded as lumbering brutes, or the other side says, 'No, they weren't that stupid. They had enormous brains, so they must have been as smart as we are,'" said study co-author Robin Dunbar, an evolutionary psychologist at the University of Oxford.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To help solve the riddle, Dunbar and his colleagues looked at 13 Neanderthal skull fossils dating from 25,000 to 75,000 years ago and compared them with 32 anatomically modern human skeletons. The researchers noticed that some of the Neanderthal fossils had much larger eye sockets, and thus eyes, than do modern humans. [10 Odd Facts About the Brain]

Low lighting

The team concluded that Neanderthals used their oversized eyes to survive in the lower-light levels in Europe, where the northern latitude means fewer of the sun's rays hit the Earth. (Modern humans also tend to have slightly bigger eyes and visual systems at higher latitudes than those living in lower latitudes, where light levels are higher.) The researchers hypothesized that Neanderthals must, therefore, also have had large brain regions devoted to visual processing.

And in fact, Neanderthal skulls suggest that the extinct hominids had elongated regions in the back of their brains, called the "Neanderthal bun," where the visual cortex lies.

"It looks like a Victorian lady's head," Dunbar told LiveScience.

Anatomically modern humans, meanwhile, evolved in Africa, where the bright light required no extra visual processing, leaving humans free to evolve larger frontal lobes.

By calculating how much brain space was needed for other tasks, the team concluded that Neanderthals had relatively less space for the frontal lobe, a brain region that controls social thinking and cultural transmission.

Isolated and dying

The findings explain why Neanderthals didn't ornament themselves or make art, Gamble told LiveScience.

These results may also help explain the Neanderthals' extinction, Dunbar said.

Smaller social brain regions meant smaller social networks. In fact, artifacts from Neanderthal sites suggest they had just a 30-mile (48.3 kilometers) trading radius, while human trade networks at the time could span 200 miles (321.9 km), Dunbar said.

With competition from humans, a bitter ice age and tiny trading networks, the Neanderthals probably couldn't access resources from better climates, which they needed in order survive, he said.

Follow Tia Ghose @tiaghose. Follow us @livescience , Facebook or Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus