Dogs Domesticated 33,000 Years Ago, Skull Suggests

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

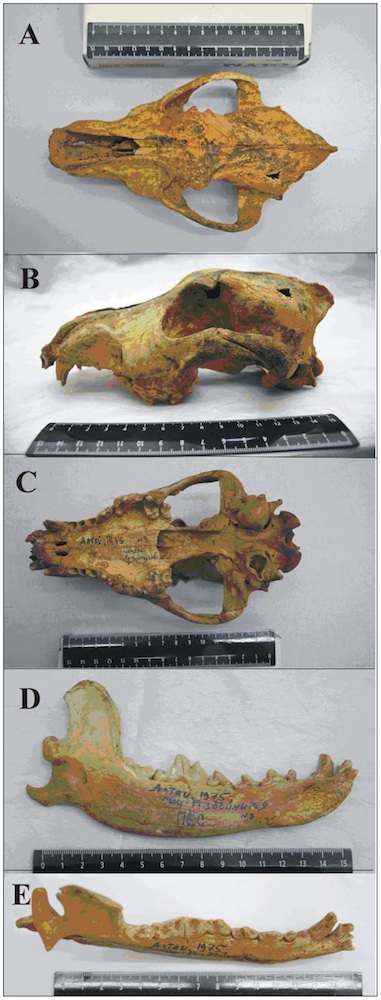

A canine skull found in the Altai Mountains of Siberia is more closely related to modern domestic dogs than to wolves, a new DNA analysis reveals.

The findings could indicate that dogs were domesticated around 33,000 years ago. The point at which wolves went from wild to man's best friend is hotly contested, though dogs were well-established in human societies by about 10,000 years ago. Dogs and humans were buried together in Germany about 14,000 years ago, a strong hint of domestication, but genetic studies have pinpointed the origin of dog domestication in both China and the Middle East.

The Altai specimen, a well-preserved skull, represents one of the two oldest possible domestic dogs ever found. Another possible domestic dog fossil, this one dated to approximately 36,000 years ago, was found in Goyet Cave, in Belgium.

Anatomical examinations of these skulls suggest they are more doglike than wolflike. To confirm, researchers from the Russian Academy of Sciences and their colleagues drilled a tiny amount of bone from the Altai dog's incisor and jaw and analyzed its DNA. They conducted all of the work in an isolated lab and used extra precautions to prevent contamination, as ancient DNA is extremely fragile.

The researchers then compared the genetic sequences from the Altai specimen with gene sequences from 72 modern dogs of 70 different breeds, 30 wolves, four coyotes and 35 prehistoric canid species from the Americas. [10 Breeds: What Your Dog Says About You]

They found that the Altai canid is more closely related to modern domestic dogs than to modern wolves, as its skull shape had previously suggested. That means that the Altai canid was an ancient dog, not an ancient wolf — though it had likely diverged from the wolf line relatively recently, the researchers report today (March 6) in the journal PLOS ONE.

If the Altai dog was really domesticated, it would push back the origin of today's house pets more than 15,000 years and move the earliest domestication out of the Middle East or East Asia, as previous studies have suggested. However, the analysis was limited to only a portion of the genome, the researchers wrote.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Additional discoveries of ancient doglike remains are essential for further narrowing the time and region of origin for the domestic dog," they said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas @sipappas. Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience, Facebook or Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus