How to 'Hear' the Russian Meteor Explosion

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

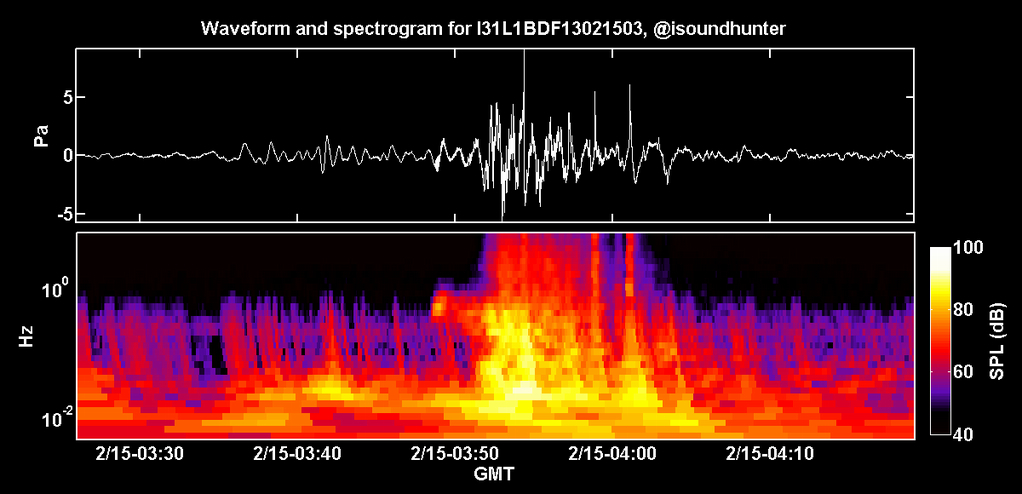

A new recording lets human ears listen in on the largest infrasound blasts ever recorded, created by the meteor that exploded over Russia last week.

Infrasonic waves from the Russian meteor fireball were picked up by 17 infrasound stations around the world, part of a network for detecting nuclear weapon explosions. Stations as far away as Antarctica tracked the blast's low-frequency waves as they traveled through Earth's atmosphere.

The signal was filtered and sped up 135 times to make it audible to human ears, according to the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), which runs the stations. [Listen to the recording]

The meteor blast was not a fixed explosion, Pierrick Mialle, an acoustic scientist for the CTBTO, said in a statement. Instead, the meteor was traveling faster than the speed of sound, burning up as it went. "That's how we distinguish it from mining blasts or volcanic eruptions," he said.

Mialle said that scientists around the world will use the infrasound data to learn more about the meteor's final altitude, how much energy it released and how it disintegrated.

Based on scrutiny of infrasound records, NASA scientists initially concluded the fireball released about 300 kilotons of energy, Bill Cooke, head of the Meteoroid Environments Office at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., said Feb. 17.

Reach Becky Oskin at boskin@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus