A 1,500-year drought in Australia may have led to the demise of an ancient aboriginal culture, a new study suggests.

The results, published Nov. 28 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, show that geological traces of a mega-drought in the northwest Kimberley region of Western Australia coincide with a gap and transition in the region's rock art style. The finding suggests that the people who lived prior to the drought, called the Gwion, either left the region or dramatically altered their culture as a result of the drought, and a new culture called the Wanjinda eventually took its place.

"There is this significant gap in rock art. A possible reason for that is that the climate at that time changed so markedly that the artists who produced the Gwion Gwion art moved on from the Kimberley region," said study co-author Hamish McGowan, a climatologist at the University of Queensland in Australia.

But not everyone agrees with that interpretation. While the evidence for a drought is very convincing, archaeological sites show continuous occupation during that time, said Peter Veth, an archaeologist at the University of Western Australia who is an expert in the Kimberley's rock art and was not involved in the study.

"They reconfigure themselves on the land and often do portray things quite differently, but I don't see it as a different people," Veth told LiveScience.

Ancient inhabitants

Aboriginal cultures have inhabited Northwest Australia for the past roughly 45,000 years, McGowan said. But at least 17,000 years ago during the Pleistocene Era, a culture called the Gwion began depicting aspects of their life on the rocks in the region. The Gwion art depicted some extinct animals (such as a marsupial lion that went extinct during the last ice age) but also groups of slim figures in what look like ancient celebrations. [Image Gallery: Europe's Oldest Rock Art]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

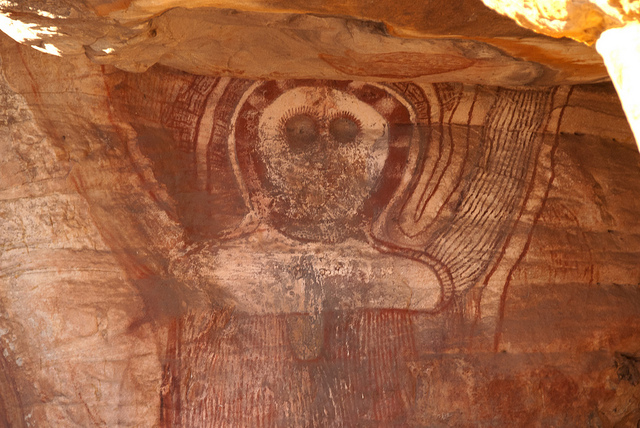

But between 5,000 and 7,000 years ago, traces of the Gwion rock art disappeared, and it wasn't until around 4,000 years ago when a new style of rock-art painting called the Wandjina, which depicts round faces with big eyes, emerged. It is still practiced today.

Pollen record

To understand why the rock art changed, McGowan and his colleagues analyzed sediments drilled from Black Springs, Australia. They found that around 6,300 years ago, the type of pollen started to change, suggesting a transition from a lush environment to one characterized by scrubby forests and open grasslands. The sediments also show an increase in dust, suggesting much drier conditions.

The results painted a picture of an ancient mega-drought that roughly coincided with the disappearance of Gwion art, McGowan said.

"The northwest of Australia can undergo very substantive natural changes in climate, which in the past have severely impacted Aboriginal society," he told LiveScience, adding the climate change and disappearance of Gwion art suggest these people left the region.

But while it's likely that the drought radically altered the local societies, the rock art from the area isn't dated well enough to make conclusions about the complete disappearance of the culture, Veth said.

What's more, archaeological evidence suggests the area was continuously occupied, he told LiveScience. For instance, archaeologists find very similar stone tools throughout the drought, Veth said.

"They have identified a very interesting climate episode and it does seem to correlate with this switch — and that's the word I would use — a switch in the way people are portraying art," he said.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.