Huge cemetery with at least 250 rock-cut tombs discovered in Egypt

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

About 250 tombs, some with fancy layouts and hieroglyphics, have been discovered cut into a hill at Al-Hamidiyah cemetery to the east of Sohag, in Egypt's Eastern Desert, about 240 miles (386 kilometers) southeast of Cairo, Egypt's antiquities ministry said.

The tombs were constructed at different times in Egypt's history, the archaeologists said in a statement from the ministry. The earliest were constructed about 4,200 years ago, at a time when Egypt's "Old Kingdom," as modern-day Egyptologists call it, was collapsing. At this time, the pharaohs of Egypt were losing control of the country, as a number of local governors gained power. Why these tombs were cut into the hill is not clear but it was not an uncommon practice in ancient Egypt.

Related: See photos of Egypt's majestic Valley of the Kings

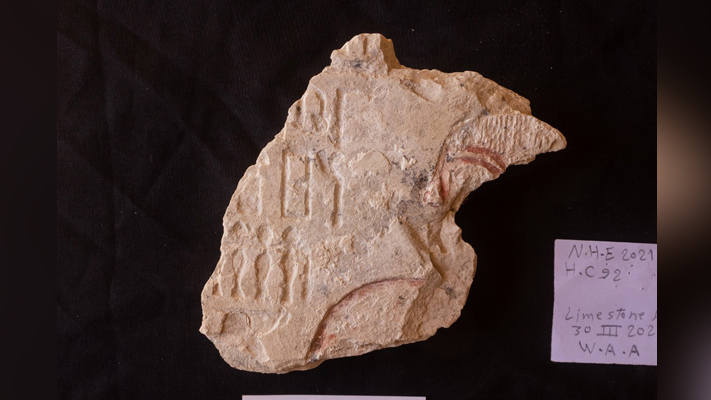

The tombs in the cemetery that date to the end of the Old Kingdom tended to have more elaborate architecture that included an entrance corridor leading down to a gallery with a burial room located in the southeast part of the structure. The archaeologists also found pieces of limestone with hieroglyphic inscriptions in some of these tombs; they also discovered what may be the remains of plates that were placed as funerary offerings to tomb owners, the ministry said in the statement.

In one tomb that dated to the end of the Old Kingdom, archaeologists found paintings that depict the tomb owner slaughtering animal sacrifices, and people making offerings for the deceased, Mostafa Waziri, secretary-general of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities, said in the statement.

The latest of the tombs found in the cemetery date to almost 2,100 years ago, the end of what modern-day scholars call the "Ptolemaic Period." At this time, pharaohs descended from Ptolemy I, who was one of Alexander the Great's generals, ruled Egypt. Roman power in the region was growing around 2,100 years ago, and in 30 B.C., after Cleopatra VII died by suicide, Egypt became a Roman province.

The team discovered numerous artifacts inside the tombs, including cups, jars and plates — some of which were full-sized examples that may have been used in daily life, and others that were miniature vessels possibly used as symbolic offerings for the deceased, the ministry said in the statement. The tombs also contained painted spherical vessels that could have been used to store liquids. What was left of a round metal mirror was found in one tomb, and many of the tombs held both animal and human remains.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Research at the site is ongoing and more tombs may be found in the future, Waziri said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus