90% Chance 2012 Will Be Warmest Year on Record for US

Continuing a hot trend, October was the fifth warmest across the globe since record keeping began in 1880. And climate scientists say it's likely, about 90 percent so, that 2012 will become the warmest year on record for the contiguous United States.

The last 36 Octobers, including this one, have experienced global temperatures above the 20th-century average; in fact, the past 332 months have all shown above-average temperatures globally, according to a report by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

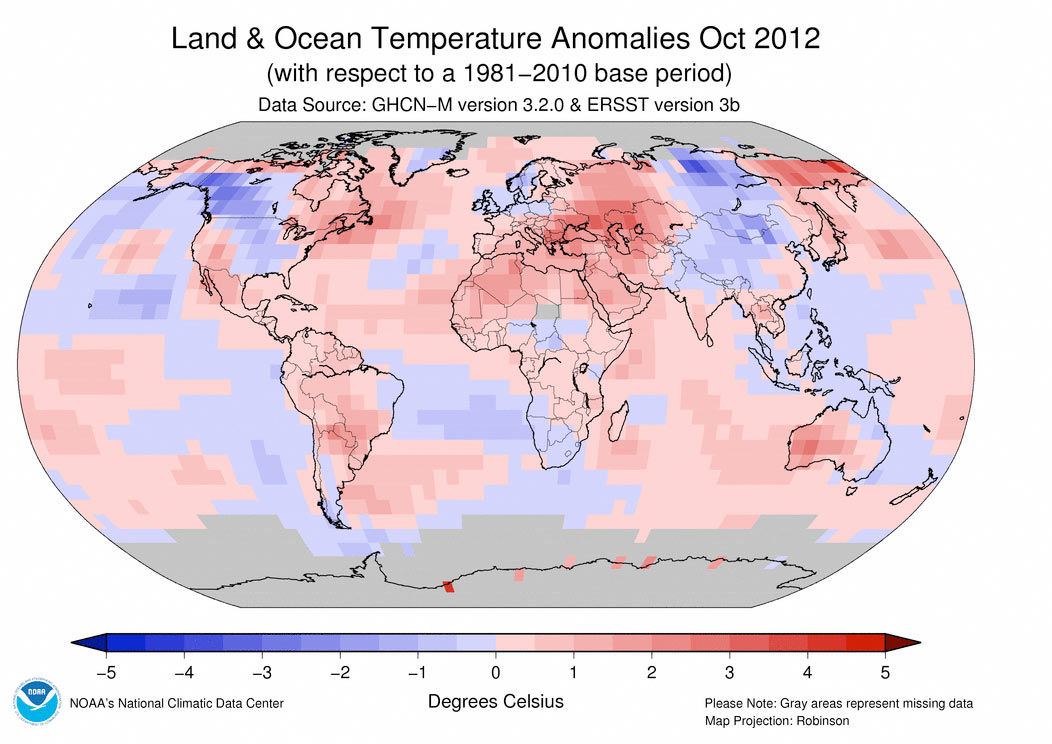

"There were no parts of the globe that were record cold during October 2012," said climatologist Jake Crouch, of NOAA's National Climatic Data Center, during a press briefing today (Nov. 15).

The last October with global temperatures dipping below the 20th-century average occurred in 1976, while the last month to do the same was February 1985, according to NOAA.

The record October temperature — 58.23 degrees F (14.63 degrees C) — refers to the combined average temperature across the planet's land and sea surfaces, reaching 1.13 degrees F (0.63 degrees C) above the 20th-century average; this also tied with the global temperature measure in October 2008. To date, this year stands as the eighth warmest on record for global average temperatures.

And based on historical records, Crouch says it's likely 2012 will end up as the warmest on record for the contiguous United States. "That's based only on historical data and doesn't take into account the forecast," Crouch told LiveScience, referring to historical data for November and December temperatures. "If we look at the forecast that the Climate Prediction Center is [giving] it's much more likely" that we'll see a record-warm year.

The current warmest year on record globally, 2010, experienced an El Niño, which is marked by warmer-than-average waters in parts of the Pacific and which drives up global temperatures.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As for what's behind the warming trends, Crouch said, "It's a combination of longer-term trends and local effects or regional effects like the drought." [8 Ways Global Warming Is Already Changing the World]

Not every region experienced above-average warmth in October, though. Below-average temperatures were seen across much of northwestern and central North America, central Asia, southern Africa and parts of western and northern Europe. For instance, the United Kingdom experienced its coldest October since 2003, with temperatures dipping about 2.3 degrees F (1.3 degrees C) below the 1981–2010 average.

Even so, record warmth dominated. Across the Republic of Moldova temperatures in October soared 4.5 to 6.3 degrees F (2.5 to 3.5 degrees C) above average. Meanwhile, in Australia, every state and territory reported above-average maximum temperatures for October, according to the NOAA report.

The Arctic sea ice doubled in size in October, the first full month of its "growing season." The ice covering Arctic waters grows and shrinks on a yearly cycle, with summer melt wrapping up in September, when it reaches its annual minimum. Through the winter, cooler temperatures cause ice to reform.

This past September saw a record low sea-ice extent, shrinking to just 1.32 million square miles (3.41 million square kilometers), according to the U.S. National Snow & Ice Data Center. And though the extent increased in October, reaching 2.7 million square miles (about 7 million square km), it was still the second smallest on record for October, behind that of October 2007.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.