Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

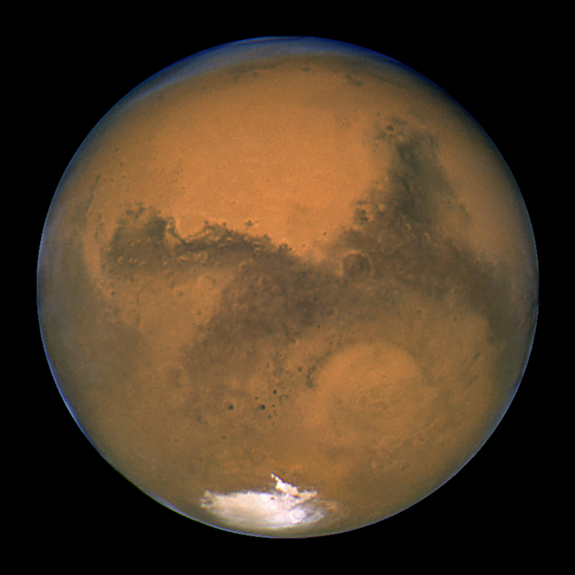

The hunt for life on Mars took a new turn today (Nov. 2), with the news that NASA's Mars rover Curiosity detected no methane in its first few sniffs of Red Planet air.

The search for Red Planet life has long been intertwined with the search for methane, which is why so many scientists and laypeople alike were probably disappointed by the initial atmospheric readings from Curiosity's Sample Analysis at Mars instrument, or SAM.

"Everybody is excited about the possibility about methane from Mars, because life as we know it produces methane," SAM co-investigator Sushil Atreya, of the University of Michigan, told reporters today.

A possible biosignature

At least 90 percent of the methane in Earth's atmosphere is biologically derived, Atreya said. As a result, many researchers regard Martian methane as a possible indicator of Red Planet life.

Further, scientists think the gas disappears rapidly from the Martian atmosphere, meaning any methane swirling there today was likely produced in the recent past.

"The conventional destruction mechanism of methane is photochemistry, as on Earth, and that results in a several-hundred-year lifetime of methane on Mars," Atreya said, adding that some of the gas is probably absorbed by the Red Planet surface as well.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But detecting lots of methane on Mars would not be convincing evidence of life by any stretch. The gas can also be produced by abiotic processes, such as the degradation of interplanetary dust particles by ultraviolet light and interactions between water and rocks. Comet strikes may also deliver methane to Mars, Atreya said.

An evolving story

Other research teams using several different ground-based and space-based instruments have detected methane in Mars air. The observed concentrations have been very low, between 10 and 50 parts per billion or so.

SAM's initial readings don't necessarily invalidate these previous measurements, researchers say. But the rover's results do highlight the need to better understand the sources and sinks of Martian methane.

Toward that end, the Curiosity team plans to keep hunting for methane over the course of Curiosity's two-year mission, which aims to determine if the Red Planet could ever have supported microbial life.

"At least for now, the sinks seem to be winning over the sources," Atreya said. "But that also could change with time."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus