Underwater Eruption Strews Ocean Surface with Dead Fish

An underwater volcano that erupted near the Canary Islands off the coast of Africa is giving scientists a closer look at how ocean ecosystems could respond to climate change, from dying fish to adapting plankton.

The ecosystem responded much as the researchers would have expected to the high temperatures and changes in acidity caused by the uneasy volcano south of El Hierro island. But the strength of the response was a surprise, study researcher Eugenio Fraile-Nuez of the Instituto Español de Oceanografía in Spain told LiveScience.

"The physical and chemical response of the system was predictable, but we never have imagined that we would reach this magnitude," Fraile-Nuez said. [Images: Wild Volcanoes]

The eruption killed or drove away all of the fish in the region (though many were seen floating dead on the ocean's surface), the researchers found. Some phytoplankton, or the floating plants that sit at the bottom of the ocean food chain, were able to adapt.

Underwater eruption

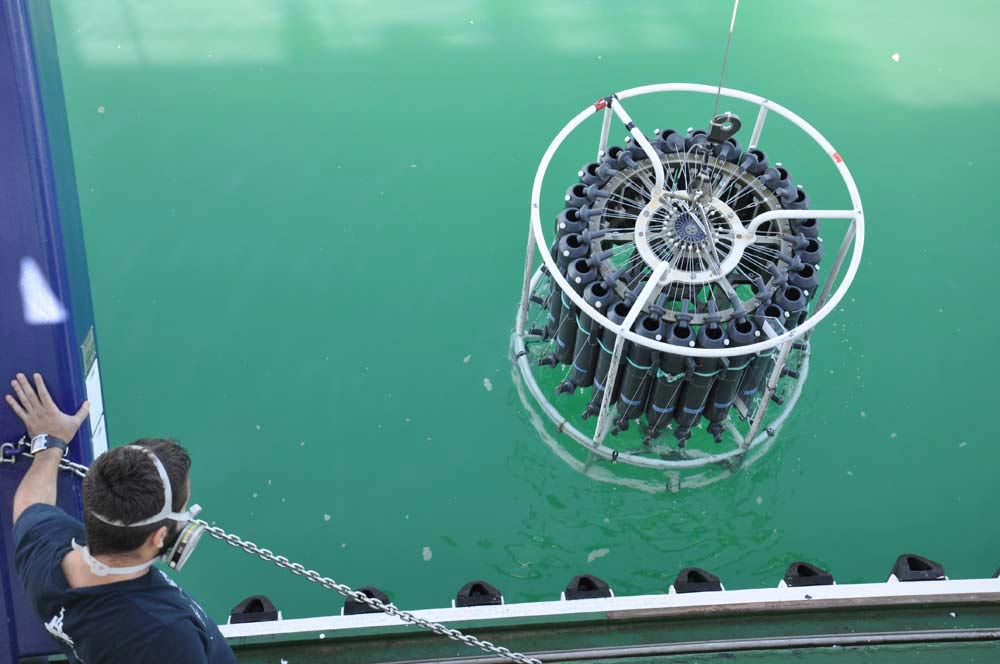

In October 2011, a new volcano formed south of El Hierro island, which is part of Spain. It was the first chance in 500 years to watch the local ecosystem evolve in response to an eruption, Fraile-Nuez said. He and his colleagues have been monitoring the volcano since then, measuring its effect on ocean temperature, salinity, carbon dioxide content and more.

Over the crater, the water heated up by as much as 65 degrees Fahrenheit (18.8 degrees Celsius), the researchers found. Dissolved oxygen in the water all but disappeared, decreasing by 90 percent to 100 percent in places. Meanwhile, carbon and carbon dioxide values shot up, and the pH of the water went down by 2.8, meaning it became more acidic.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fish died or disappeared in the wake of the underwater eruption, which also killed a massive amount of plankton in deep waters. In their place, a community of carbon-eating bacteria sprung up, many of which shone with bright green fluorescence. At the surface, plankton seemed to adapt to warmer waters and the addition of new elements such as copper, Fraile-Nuez said.

Link to climate change

Increase in temperature, decrease in oxygen and a more acidic pH is exactly what scientists would expect to be the result of global warming for the ocean, Fraile-Nuez said. As the oceans take up more and more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, scientists predict they'll respond much as the area around El Hierro has to the volcanic eruption — though not necessarily on the same scale.

Understanding the changes caused by the volcanic eruption will help researchers predict how the oceans will respond to certain levels of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide, Fraile-Nuez said.

"The orders of magnitude in which we are moving will help us to have a future vision of how the marine ecosystem of El Hierro would adapt to such changes," he said.

Fraile-Nuez and his colleagues detailed their results online this week in the open-access journal Scientific Reports.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus