Mysterious Mud Waves Found on Arctic Seafloor

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

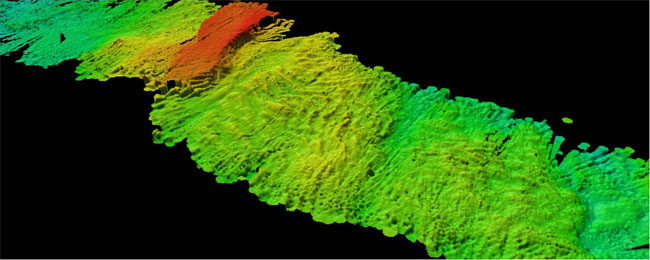

SAN FRANCISCO—Along parts of the Arctic Ocean floor, currents have driven mud into huge piles, with some "mud waves" nearly 100 feet across.

Around the world, strong currents can produce these features, piling up sediments from the ocean floor to create a wavy surface, but researchers had thought the Arctic was too calm to produce the mud waves.

The Arctic mud waves were discovered on recent expeditions to map the ocean bottom with sonar, which can view layers of sediment up to 1,000 feet below ground.

The expeditions were looking mainly for signs of the ancient ice sheets that once covered the Arctic and found evidence of massive scrapes in the ocean bottom about half a mile (1 kilometer) deep. Sonar images clearly showed these grooves running in parallel, plus boulders and other debris were revealed, left by the giant ice sheets.

In the continental shelf north of Greenland, sonar found deep scours that were undoubtedly left by ancient ice, the scientists said.

"It shows very, very clearly iceberg scours," said expedition scientist Martin Jakobsson of Stockholm University in Sweden.

The mud waves, however, were an unexpected surprise. The scientists aren't sure what formed them.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The mud waves could be caused by tidal fluctuations," said expedition scientist Leonard Polyak of Ohio State University. "But that’s really just speculation at this point."

- Video: Loss of Arctic Sea Ice

- North vs. South Pole: 10 Wild Differences

- Images: Glaciers Before and After

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus