More Evidence Says Ancient Mars Was Really Wet

Several studies over the past decade or so have shown Mars used to be warmer and wetter, but scientists are still trying to pin down the details of the Red Planet’s early history. A new study finds additional evidence that early Mars was wet — really wet — and also that its atmosphere was much thicker than today.

Early Mars would have been saturated, with air density 20 times what it is now, according to Georgia Tech Assistant Professor Josef Dufek.

Currently, the Martian atmosphere is less than 1 percent the density of Earth’s. Liquid water can’t last long, if at all, on the surface (though other studies indicate there is much ice, and perhaps liquid water, beneath the surface).

Dufek is analyzing ancient volcanic eruptions and surface observations by the Mars rover Spirit. His new findings are published by the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

“Atmospheric pressure has likely played a role in developing almost all Mars’ surface features,” he said. “The planet’s climate, the physical state of water on its surface and the potential for life are all influenced by atmospheric conditions.”

Dufek’s first research tool was a rock fragment propelled into the Martian atmosphere during a volcanic eruption roughly 3.5 billion years ago. The deposit landed in the volcanic sediment, created a divot (or bomb sag), eventually solidified and remains in the same location today. Dufek’s next tool was the Mars rover. In 2007, Spirit landed at that site, known as Home Plate, and took a closer look at the imbedded fragment. Dufek and his collaborators at the University of California-Berkeley received enough data to determine the size, depth and shape of the bomb sag.

Dufek and his team then went to the lab to create bomb sags of their own. They created beds of sand using grains the same size as those observed by Spirit. The team propelled particles of varying materials (glass, rock and steel) at different speeds into dry, damp and saturated sand beds before comparing the divots with the bomb sag on Mars. No matter the type of particle, the saturated beds consistently produced impact craters similar in shape to the Martian bomb sag.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By varying the propulsion speeds, Dufek’s team also determined that the lab particles must hit the sand at a speed of less than 40 meters per second to create similar penetration depths. In order for something to move through Mars’ atmosphere at that peak velocity, the pressure would have to be a minimum of 20 times more dense than current conditions, which suggests that early Mars must have had a thicker atmosphere.

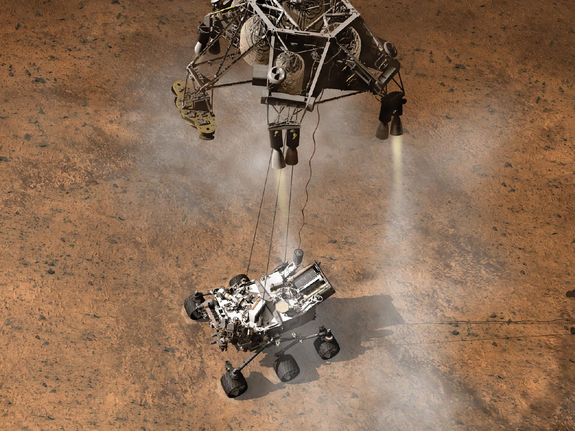

“Our study is consistent with growing research that early Mars was at least a transiently watery world with a much denser atmosphere than we see today,” said Dufek. “We were only able to study one bomb sag at one location on the Red Planet. We hope to do future tests on other samples based on observations by the next rover, Curiosity.”

Curiosity is scheduled to land on Mars in early August.