Lost 19th-century Tlingit fort discovered in Alaska

The battle was a pivotal moment in Tlingit history — and in Russia's colonization of the Americas.

The remains of a long-lost 19th-century fort in Alaska, once the site of a fierce battle between First Nations clans and Russian soldiers, has been revealed by radar scans. It was a stronghold of the Tlingit people, a Northwest Coast Indigenous group, and it was the last fort to fall before Russia colonized the land in 1804, launching six decades of occupation.

The Russians first invaded Alaska in 1799, and three years later Tlingit clans successfully repelled their would-be colonizers. Tlingit fighters then fortified their territory against future Russian attacks by building a wooden fort they named Shís'gi Noow — "the sapling fort" in the Tlingit language — at a strategic spot in what is now Sitka, Alaska, at the mouth of the peninsula's Indian River.

But two years later, Shís'gi Noow gave way to the second wave of Russian invaders; the Tlingit abandoned the fort, and the Russians destroyed it. For more than 100 years, historians and archaeologists searched for clues about where it once stood, identifying several promising locations. But the recent combination of two ground-scanning methods have finally revealed the trapezoid outline of the fort's perimeter, researchers reported in a new study.

Related: Photos: The hidden fortress beneath Alcatraz

On Oct. 1, 1804, the Russians launched a fresh attack on the fort, aided by allies from the Aleut and Alutiiq Indigenous groups, and the Tlingit promptly decimated their foes. But the Tlingit's reserve gunpowder blew up in a supply canoe; knowing that they could no longer defend the fort, the Tlingit defenders began planning their retreat, and by the time the Russians regrouped for a second assault, the stronghold was already abandoned, according to the U.S. National Parks Service (NPS).

"Russian/Aleut forces razed the abandoned structure, but not before recording a detailed map," the scientists reported in the study.

Skirmishes between Russian and Tlingit forces continued, but the Russians were there to stay — at least, until they sold their Alaskan interests to the U.S. government in 1867, according to the NPS.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Historical descriptions of the fort's whereabouts relied on nearby landscape features, offering only a general suggestion of where the fort stood. But the exact location was always uncertain, "with several alternative spots suggested over the years," lead study author Thomas Urban, a research scientist in the College of Arts and Sciences at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, told Live Science in an email.

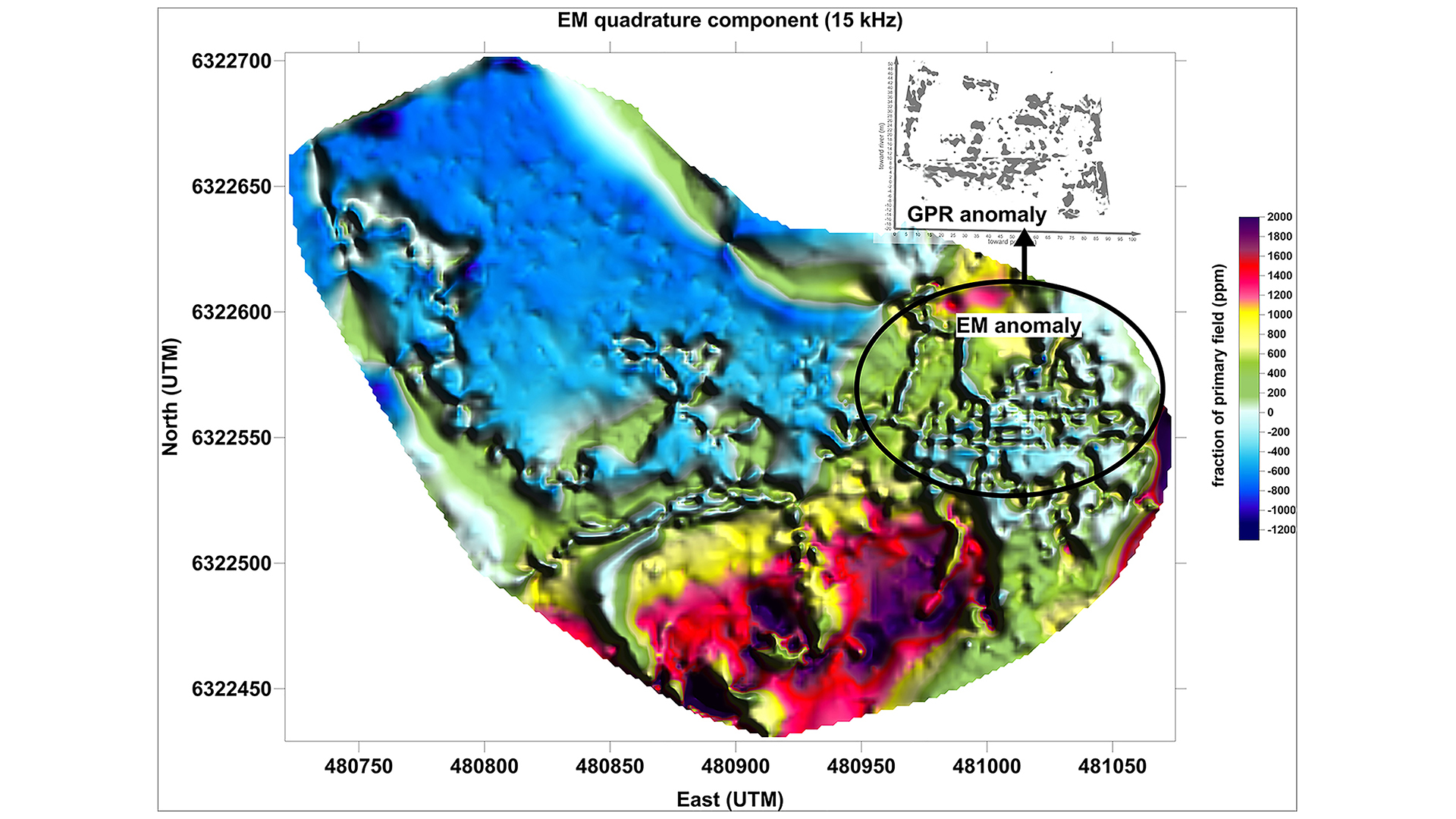

"An early investigation in the 1950s claimed to have found wood from the western wall of the fort, and investigations in the 2000s located shot and cannon balls in roughly the same vicinity," Urban said. These clues were promising, but the picture remained incomplete, so Urban and study co-author Brinnen Carter, a cultural resource program manager at Shenandoah National Park in Virginia, conducted a large-scale geophysical survey using electromagnetic induction (EM) and ground-penetrating radar (GPR).

Throughout the process, the team consulted with Sitka Tribe of Alaska, getting permission for the nondestructive survey and having tribal councils review the findings, Carter said.

GPR scans subsurface structures with radar pulses in the microwave band of the spectrum, while EM scans underground structures by measuring electrical conductivity. The researchers scanned an area measuring 0.07 square miles (0.17 square kilometers, or 17 hectares), "the largest archaeological geophysical survey ever undertaken in Alaska," the authors reported.

When Urban and Carter compared the results of their surveys, they found that both methods detected similar patterns underground that matched historic descriptions of the fort's size and shape. Metallic "anomalies" in the data may have come from stray cannonballs, which prior excavations had already identified in the area, according to the study.

What's more, the EM survey, which covered more ground than GPR scans, did not reveal any other plausible signals in the region that could indicate an alternative location for the long-lost fort.

"We therefore believe that the geophysical survey has yielded the only convincing, multi-method evidence to date for the location of the sapling fort — a significant cultural resource in New World colonial history and an important cultural symbol of Tlingit resistance to colonization," the scientists reported.

The findings were published online Jan. 25 in the journal Antiquity.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus