Extreme Impacts Study Aims to Build Captain America's New Shield

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

When a material undergoes a fast, hard impact — such as armor being struck by a bullet — what happens next? Johns Hopkins University is opening an institute just for the study of what happens to materials during high-impact collisions and other examples of "extreme materials science."

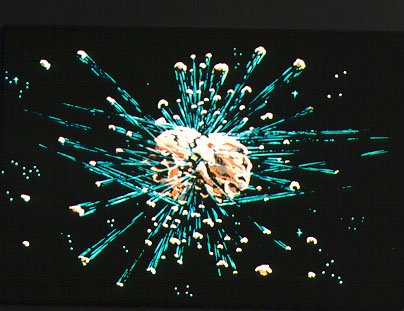

In an example of what they'll examine, engineers from the Baltimore university have posted a video that shows a cube of basalt and glass shattering after being struck by a Pyrex sphere traveling one kilometer (0.6 miles) per second, or three times the speed of sound. The video itself was recorded at 23,000 frames per second.

Johns Hopkins received a $90 million grant from the U.S. Army earlier this month to assemble a team of experts from various sectors, including other universities, and develop new lightweight protective materials for people and vehicles.

"The vision of the institute is to tackle the science issues associated with extreme events, and in this case to work with the Army to better protect our troops," new institute director K.T. Ramesh said in a statement.

Researchers at the Hopkins Extreme Materials Institute will study what happens at the atomic level when metals, ceramics, polymers and more are hit at high velocities. They'll focus on basic research; the manufacture of armoring materials based on their findings will be left to others.

"This is how I think about our effort with the Army: Captain America needs a new shield, and we're going to work with the Army to build it," said Ramesh, a Johns Hopkins engineering school professor.

Their work won't just apply to shielding and armoring, according to the university. High-impact studies can help scientists understand the dust particles that explosions create, and even can help them plan how to divert or break up an asteroid aimed at Earth,

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to Live Science. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus