Radiation Blast from Big Solar Flare May Threaten Satellites

A radiation wave kicked up by the eruption of a powerful solar flare late Sunday (March 4) will likely miss the Earth, but could catch several NASA satellites in its crosshairs, scientists say.

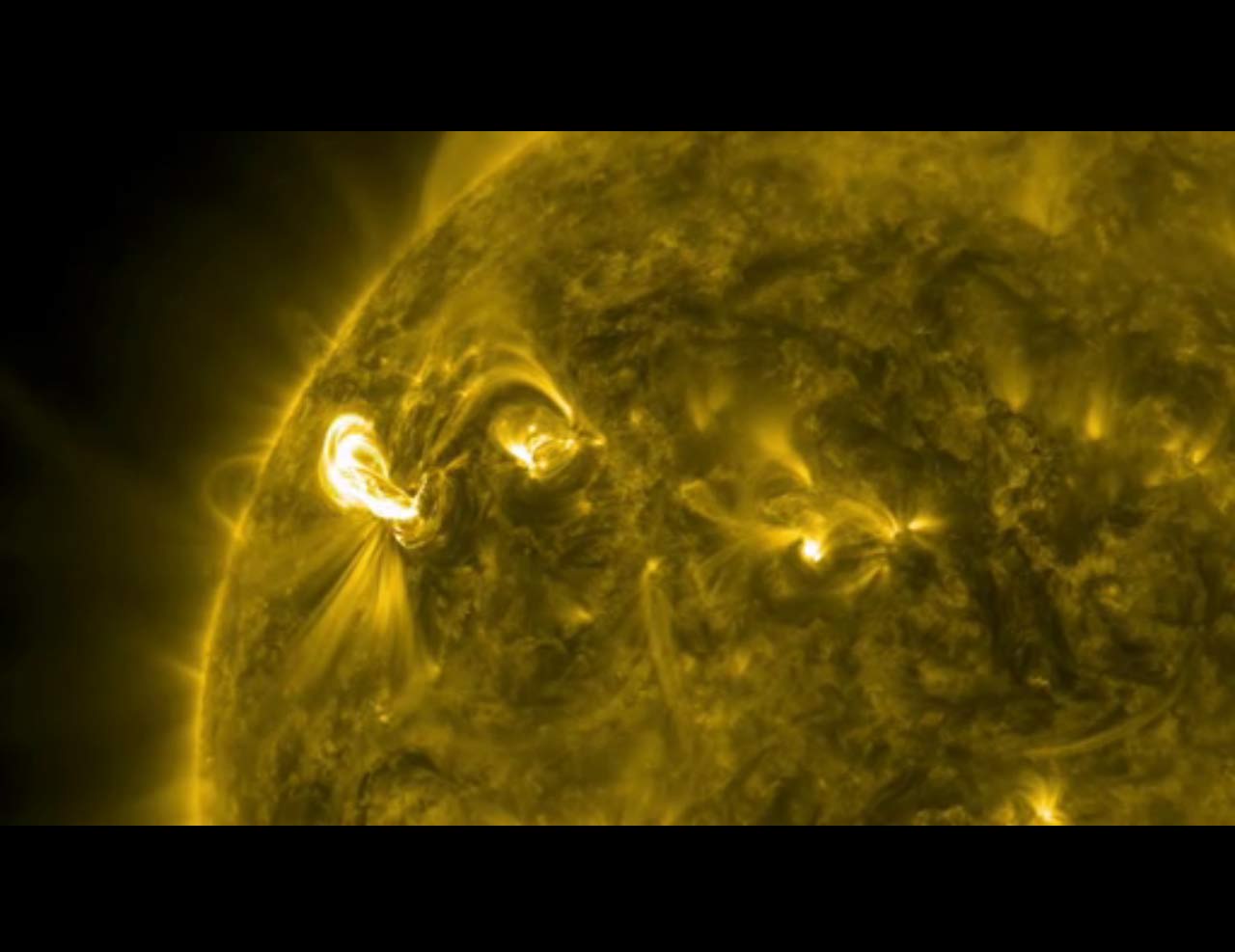

The radiation concern stems from an X1.1-class flare (the strongest type of sun storm) that blasted from the surface of the sun last night at 11:13 p.m. EST (0413 GMT March 5). The flare unleashed a cloud of charged particles, called a coronal mass ejection (CME).

This wave of solar plasma will mostly miss hitting Earth, but some spacecraft, including NASA's sun-watching Stereo B satellite, the Messenger spacecraft at Mercury and the agency's infrared Spitzer Space Telescope, are in path of the resulting radiation storm, according to scientists at the Space Weather Center at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

"It's a shower of radiation, and this high-energy radiation can impact spacecraft and some of the instruments," Yihua Zheng, a lead researcher at the Space Weather Center, told SPACE.com. "Stereo B has already seen some radiation, but we don't have real-time data from the other spacecraft, so we don't know for sure. But, based on the location and the size of the CME, we think those spacecraft are likely to receive a high dose of radiation."

Zheng and her colleagues at the Space Weather Center issued alerts to the scientists who manage the Stereo, Messenger and Spitzer missions so that they can take the necessary precautions to protect the probes and their onboard instruments. [Worst Solar Storms in History]

"It's up to the mission control people — they know how the instruments and the spacecraft behave," Zheng said. "They will do some preventative measures and just monitor the situation. We provide the information, but it's really up to each individual spacecraft's mission control team."

Last night's solar flare is only the second X-class eruption so far this year. X-class flares are the most powerful type of solar storm. M-class eruptions are considered mid-range, and C-class flares are the weakest.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

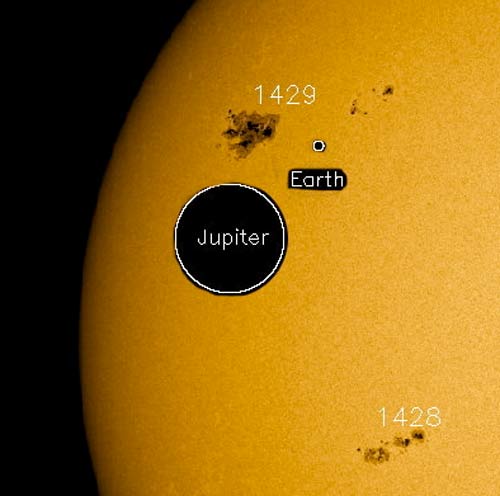

The eruption came from a massive sunspot region called AR1429, which is at least four to five times larger than Earth, Zheng said. The AR1429 sunspot region continues to be quite active since it emerged on March 2, and scientists are predicting it will spew more flares as the week goes on.

When a powerful X-class flare is aimed directly at Earth, it can sometimes cause significant disruptions to satellites in space and power grids and communications infrastructure on the ground. Strong flares and CMEs can also pose potential hazards to astronauts on the International Space Station.

While the CME triggered by last night's flare is not expected to hit Earth, scientists will continue to closely monitor the situation. Experts at the Space Weather Prediction Center, which is operated by the National Weather Service, anticipate only minor geomagnetic storms beginning late Tuesday (March 6) and lasting through Wednesday (March 7).

"Earth won't see much impact," Zheng said. "The radiation is also going to miss Earth a little bit — we could still see some enhancements, but they won't be dramatic."

The sun's activity ebbs and flows on an 11-year cycle. The sun is in the midst of Solar Cycle 24, and activity is expected to ramp up toward the solar maximum in 2013.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com staff writer Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus