New Fingerprint Technique Could Reveal Diet, Sex, Race

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A victim might not care if a murderer is a smoker or a vegetarian. But having such knowledge could help police solve a case. Details like this could one day be at their fingertips if a new fingerprinting technique pans out as expected.

Standard methods for collecting fingerprints at crime scenes, which involve powders, liquids or vapors, can alter the prints and erase valuable forensic clues, including traces of chemicals that might be in the prints.

Now researchers find tape made from gelatin could enable forensics teams to chemically analyze prints gathered at crime scenes, yielding more specific information about miscreants' diets and even possibly their gender and race.

Nimble technique

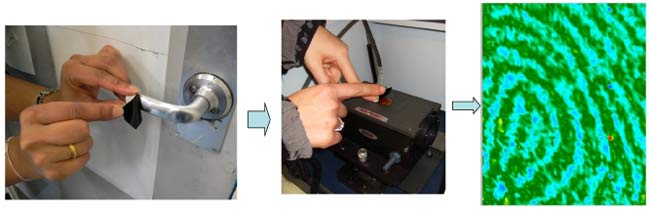

The gel tape can gather prints from a variety of surfaces, including door handles, mug handles, curved glass and computer screens, just as conventional fingerprint techniques can. The gelatin is then irradiated with infrared rays inside a highly sensitive instrument that rapidly takes a kind of "chemical photograph," identifying molecules within the print in 30 seconds or less, said physical chemist Sergei Kazarian at Imperial College London.

Fingerprints contain just a few millionths of a gram of fluid, or roughly the same amount of material in a grain of sand. That might, however, be enough to determine valuable clues about a person beyond the print itself, such as their gender, race, diet and lifestyle, Kazarian and his colleagues find.

For instance, preliminary results could identify males based on the greater amounts of urea in their fingerprints—urea being the key ingredient of urine. The complex brew of organic chemicals within prints might also shed light on the age and race of people, and hold traces of items people came into contact with, such as gunpowder, smoke, drugs, explosives, or biological or chemical weapons.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Even a person's diet might be determined from fingerprints, as vegetarians may have different amino acid content than others, Kazarian said.

"More volunteers need to be tested for statistical information on fingerprints with regard to race, sex and so on, but we believe this will be a powerful tool," he told LiveScience.

Much faster

In addition, unlike conventional fingerprint techniques, the new method did not distort or destroy the original prints, instead keeping them intact and available for further analysis, the researchers said. Their findings are detailed in the Aug. 1 issue of the journal Analytical Chemistry.

Other techniques can analyze chemicals in fingerprints, including methods that use X-rays. Still, Georgia Tech analytical chemist Facundo Fernandez noted this new technique "is very rapid. You cannot say the same for other approaches." Fernandez was not involved in the current study.

Kazarian said his group's technique is especially good at identifying organic deposits, the main components of fingerprints.

- Great Inventions: Quiz Yourself

- Do Identical Twins Have Identical Fingerprints?

- Top 10 Unexplained Phenomena

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus