For Sale: Pieces of Polar Explorers' Dramatic Past

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A century after the golden age of polar exploration, ordinary folks with some spending money and a taste for adventure — but who'd rather forego the frostbite, starvation and killer-whale attacks — can own a piece of the compelling story of humankind's fevered race to the Earth's poles.

This week, Leski Auctions in Melbourne, Australia, is offering up 101 photographs, documents, books, letters, stamps, illustrations and other memorabilia from polar journeysboth Arctic and Antarctic. Mementoes from many of polar exploration's biggest names — Cook, Peary, Shackleton — are up for sale. (Later this month, Christie's is selling a well-preserved cracker that British explorer Ernest Shackleton left behind in Antarctica during his first expedition to the southernmost continent, from 1907 to 1909.)

Yet some of the priciest items on offer are photographs from the famed race to conquer the South Pole, which this year is celebrating its centenary. The grueling contest pitted British explorer Robert Falcon Scott against Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, who claimed victory on Dec. 14, 1911 — a full month before Scott's team arrived.

The race made Amundsen a hero. Scott never made it home.

Antarctic living

The photographs on the auction block tell Scott's side of the story — a tale fraught with nationalism, narcissism, bravery, sacrifice, and, ultimately, for Scott and several of his men, a frigid and lonely death. [See photographs from Scott's expedition.]

"It's such a complicated story of meaningless failure at one level and heroic transcendence on the other," said Ross MacPhee, curator of vertebrate zoology at the American Museum of Natural History, and author of the book, "Race to The End: Amundsen, Scott, and the Attainment of the South Pole" (Sterling Innovation, 2010).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For sale this week are more than a dozen images taken by Herbert George Ponting, Scott's official photographer. Although many images show daily life during the 1910 to 1912 expedition — penguins, seals, desolate expanses of glittering ice — several depict aspects of Scott's expedition that some have pointed to as signs of foolhardy decisions that led to his downfall.

One photograph shows some of the 19 Siberian ponies Scott brought to Antarctica for the trek to the Pole. [See the horses here.]

"There's nothing for them to eat there, and they're herbivores, so you can't feed them to each other like dogs," MacPhee said.

However, he added, horses weren't a totally outlandish choice. Scott knew Shackleton had used horses in Antarctica — and they're far stronger pack animals than dogs. "It was not a completely ludicrous idea to use ponies, but on the other hand it wasn't a great one either," MacPhee said.

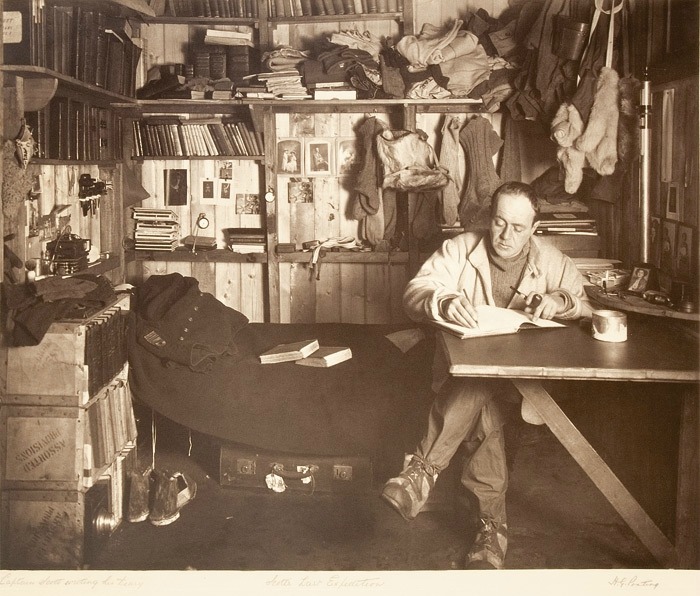

Another photograph shows Scott seated at a desk in the comfortably appointed "hut" the expedition built. The wooden building, which still stands today, was large enough to accommodate nearly two dozen men, and was outfitted with piles of books, a gramophone, and even a player piano.

Again, MacPhee explained, these were not senseless luxuries. The team planned to be there for a long time. "And with the vagaries of the weather — there's such a narrow window for vessels to come and go — they had to prepare for every exigency," MacPhee said. "With those long Antarctic nights, you want to fill them with something."

As shown in Ponting's photograph, Scott often filled his nights by writing in his diary. The image was taken in early October 1911, just three weeks before Scott set off for the Antarctic interior.

Antarctic death

Two-and-a-half months after they began, Scott, along with four of his men, reached the South Pole on Jan. 17, 1912 — only to discover a Norwegian flag standing at the spot. Ill-equipped, and hampered by the tightening grip of the harsh Antarctic winter, all five men perished on the return trek.

It is Scott's faithful records of his journey, uncovered near his frozen corpse nearly 6 months after his death in March 1912, that revealed the true fate of the men who set off to conquer the Pole and never returned.

"The last three remaining companions soldiered on until the last moment," MacPhee said. "You just have to be impressed with what these fellows put up with."

Charles Leski, the man behind Leski auctions, said this week's sale has special meaning. He himself was ensnared by the romance of polar exploration as a young stamp collector in 1961, on the 50th anniversary of Australia's first Antarctic expedition; he finally visited Antarctica in 2004.

"I felt ecstatic surrounded by such rare beauty, silence and a sense of isolation," Leski said, adding that someday he hopes to make it as far as the South Pole.

Although Scott didn't survive his own trek to the South Pole, he did set a precedent that has little to do with purely nationalistic glory.

"Scott was very, very keen on scientists taking part in his expeditions, and it actually cost him to have these nonproductive types along, who were just there to collect information," MacPhee said.

Thanks, in part, to Scott's example, polar science has become a priority, and an increasingly important one. "And we recognize that now," MacPhee said, "how with climate change, the poles are the bellwethers for what is going on."

The Amundsen-Scott South Pole research station is staffed with scientists year-round; scientists have been working at the Pole since the 1950s, when the first permanent structure was built there.

"Every scientist working in Antarctica today owes Scott something," MacPhee said.

- The Harshest Environments on Earth

- Gallery: Scientists at the Ends of the Earth

- Album: Stunning Photos of Antarctic Ice

You can follow OurAmazingPlanet staff writer Andrea Mustain on Twitter: @andreamustain. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus