Our Bizarre Relatives: A Sea Squirt Family Album

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

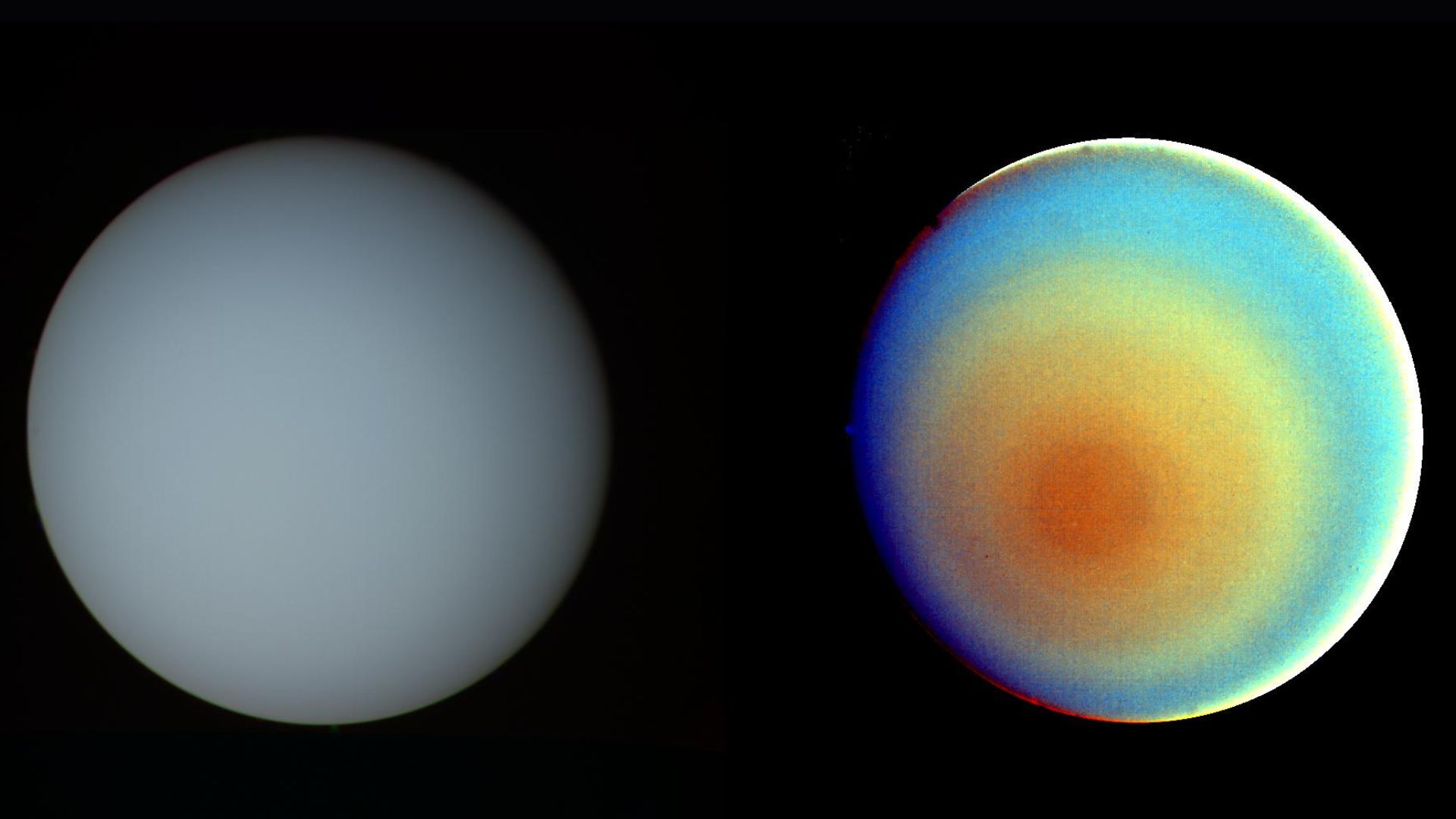

Strength in Numbers

Sea squirts take many forms, small ones, like those shown above, cluster together, ultimately forming colonies, while others live on their own. Although considered invertebrates, sea squirts are surprisingly like us: Recent research has even shown that their tiny hearts use a pacemaker mechanism similar to ours. Some sea squirts are also invasive pests, coating the sea floor and other surfaces, and threatening fish and shellfish.

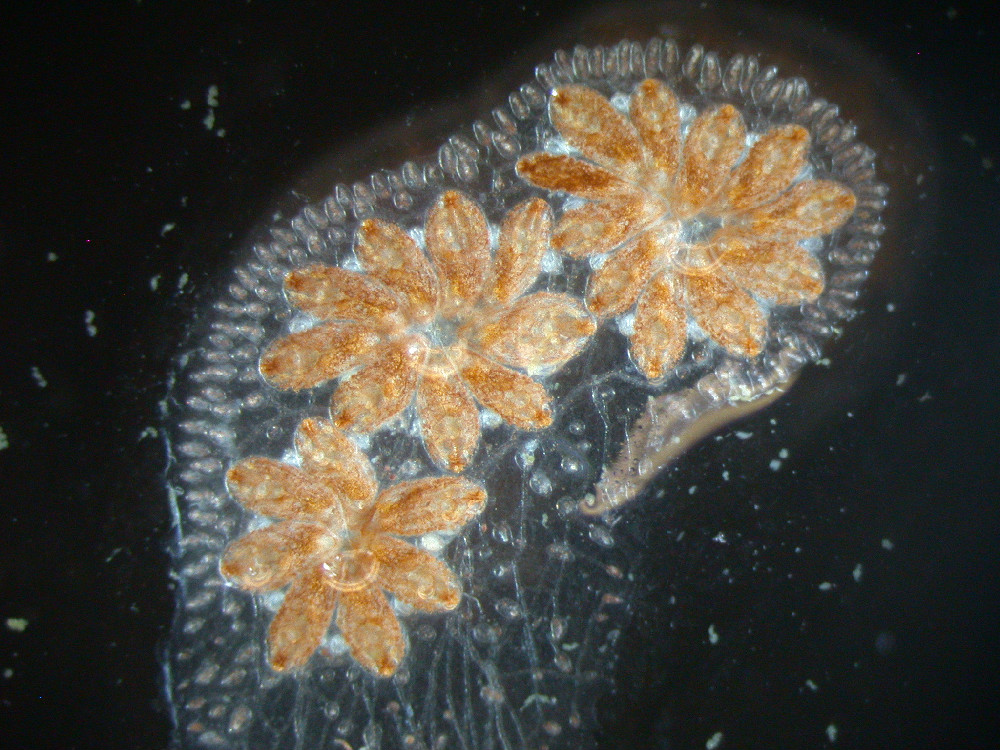

Come Together

Each petal in these clusters is an individual sea squirt. These adult sea squirts cluster together to form systems, the flower-like structures shown above. The systems then join to build colonies.

Sea Vases

These sea squirts, Ciona intestinalis live independently, not in colonies, and are called sea vases because of their shape. They were collected in Woods Hole, Mass.

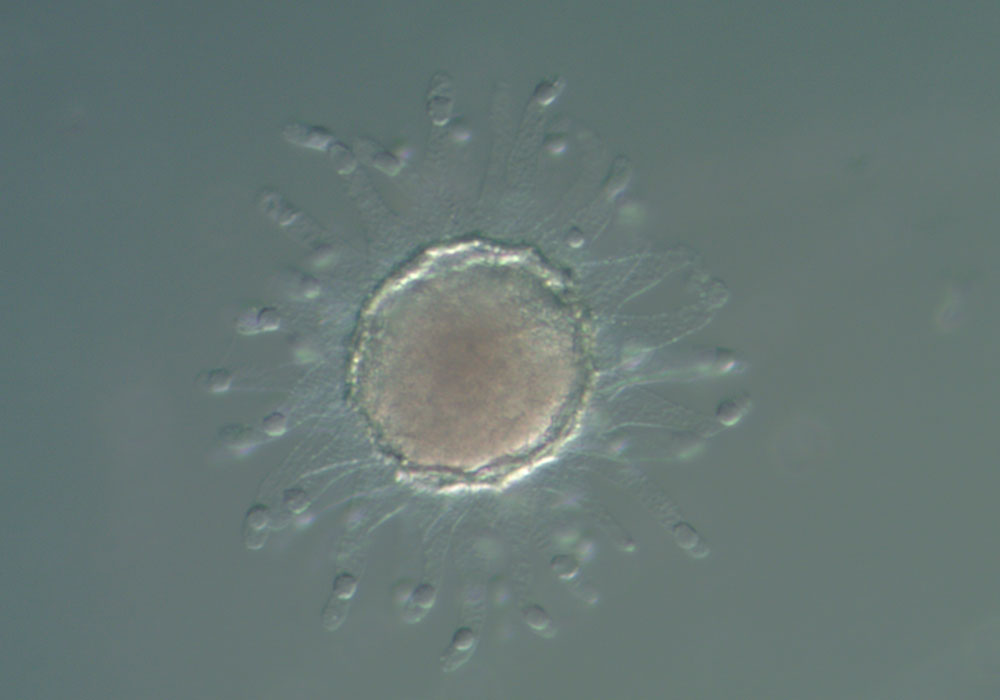

At The Begining

A Ciona intestinalis embryo.

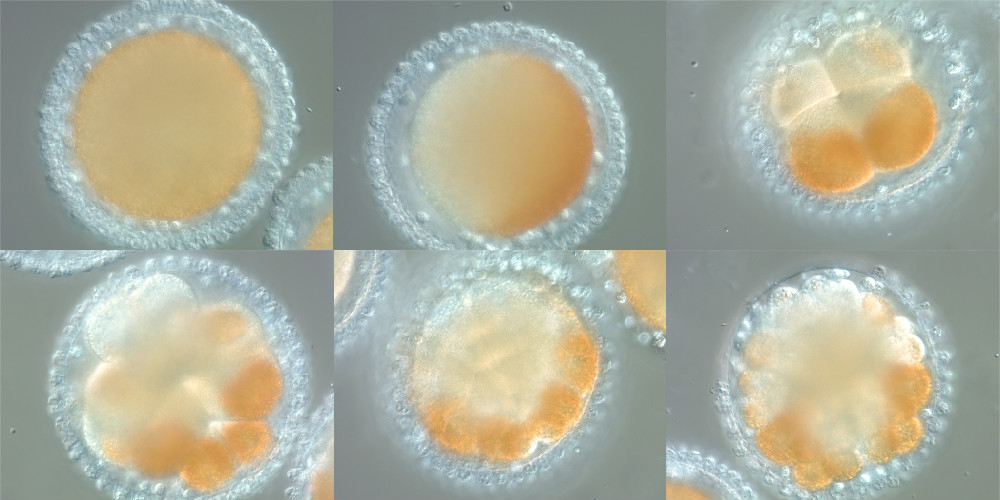

A Growing Sea Squirt

This montage shows the cell divisions of a sea squirt embryo, a species called Boltenia villosa or spiny-headed tunicate. Any cell that inherits the orange pigment, generally on the lower right side of the embryo, becomes muscle.

Our Invertebrate Relative

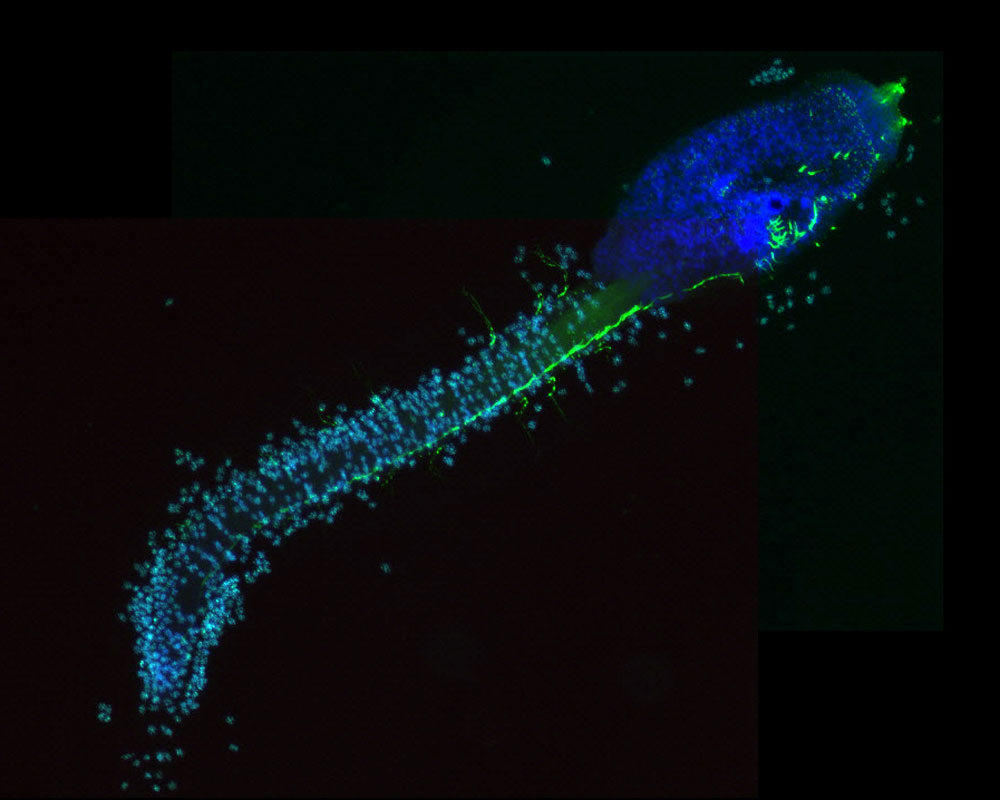

A fluorescent microscope image of a larval sea squirt of the species Ciona intestinalis. Sea squirt larvae resemble tadpoles and have primitive backbones, called notochords, revealing their surprisingly close relationship to us.

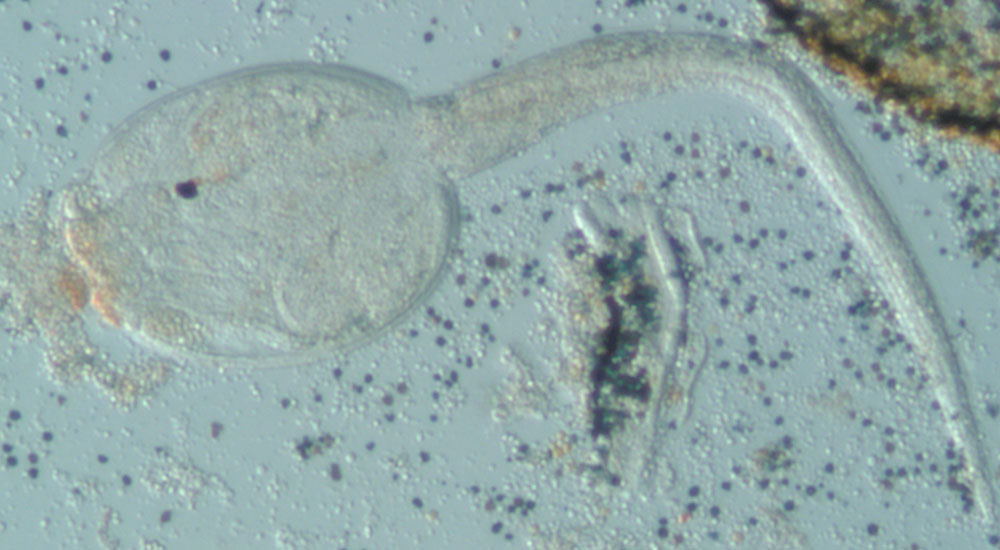

Sea Squirt Tadpole

Another tadpole, this one from the colonial species Botryllus schlosseri shown under regular light.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

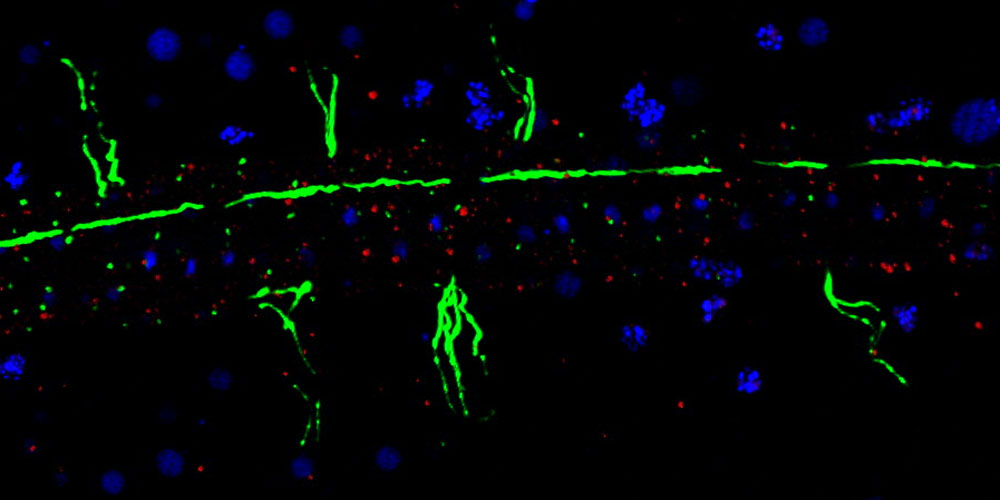

Nerves of Sea Squirt

The green lines in this microscope image depict the nerves within the tail of a Ciona intestinalis sea squirt larva.

Colonial Pump

The star sea squirt, Botryllus schlosseri, was introduced from Europe. The organism is colonial, with each individual, called a zooid, pumping water through its siphon, filtering out oxygen and then feeding on the small organisms suspended in the water. A colony consists of many star-shaped clusters.

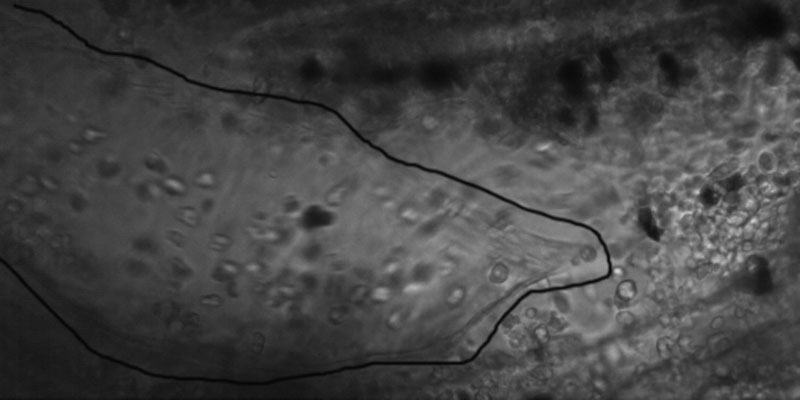

A Tube Heart

Each sea squirt, whether an individual or member of a colony, has a heart. The heart of an animal within a colony of Botryllus schlosseri is outlined above. Recent research indicates that this sea squirt uses a mechanism similar to our own to keep their heart beat going.

Transparent Chain

The colonial chain tunicate, Botrylloides violaceus, originated in Japan, China and southern Siberia, and then was introduced to Pacific Northwest waters. The colony of individuals is arranged such that it appears as a clear, fleshy matrix, with systems of dozens of individuals seen on the surface as elongated ovals or chains.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus