Dim Sun Helped Send Earth into Little Ice Age, Study Suggests

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

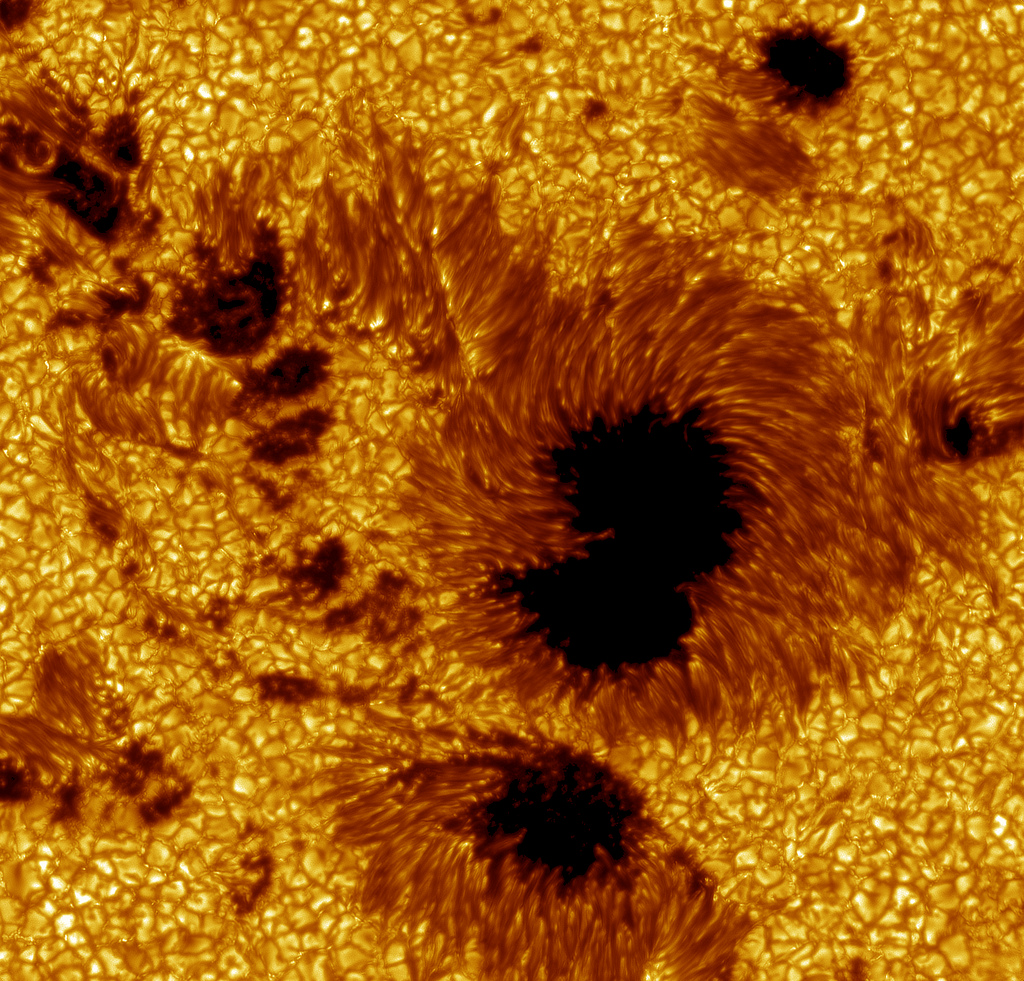

A dearth of bright spots on the sun might have contributed to a frigid period known as the "little ice age" in the middle of the past millennium, researchers suggest.

From the 1500s to the 1800s, much of Europe and North America were plunged into what came to be called the little ice age. The coolest part of this cold spell coincided with a 75-year period beginning in 1645 when astronomers detected almost no sunspots on the sun, a time now referred to as the Maunder Minimum.

Past studies had mulled over whether the decreased solar activity seen during the Maunder Minimum might have helped cause the little ice age. Although sunspots are cool, dark regions on the sun, their absence suggests there was less solar activity in general. Now scientists suggest there might have been fewer intensely bright spots known as faculae on the sun as well during that time, potentially reducing its brightness enough to cool the Earth.

The dip in the number of faculae in the 17th century might have dimmed the sun by just 0.2 percent, which may have been enough to help trigger a brief, radical climate shift on Earth, researcher Peter Foukal, a solar physicist at research company Heliophysics in Nahant, Mass., told LiveScience.

"The sun may have dimmed more than we thought," Foukal said.

Foukal emphasized this dimming might not have been the only or even main cause of the cooling seen during the little ice age. "There were also strong volcanic effects involved — something like 17 huge volcanic eruptions then," he said.

Foukal also cautioned these findings regarding the sun did not apply to modern-day global warming. "Increased solar activity would not have anything to do with the global warming seen in the last 100 years," he explained. [10 Surprising Results of Global Warming]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Foukal and his colleagues detailed their findings May 27 at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Boston.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus